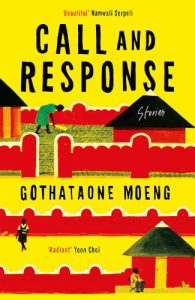

The JRB presents an excerpt from Call and Response, the debut short story collection from Gothataone Moeng.

Call and Response

Gothataone Moeng

Oneworld, 2023

Read the excerpt:

The First Virginity of Gigi Kaisara

She was a beloved girl, so she had accumulated many names. On her birth certificate: Gagontswe Kaisara, two names that had little to do with her. The first she had been given by her father, a hand-me-down, after an aunt of his who had never returned from domestic work in Johannesburg; the second was a family heirloom, belonging first to her great-grandfather, then to her grandfather, both of whom had died before she was born, so she didn’t even know them as she lugged their name around. Also, on her birth and PSLE certificates: Penelope—her most despised name, a name given to her by her mother for no reason other than its elegance and symmetry, its appearance on the page. Only her teachers and classmates at the private boarding school she attended in Gaborone used that name. They chopped it up; they remixed it as they saw fit. Penlop, she answered to sometimes, Penny, Pen, Pen-Pen, P. To her father, she was Nono, after some or other adorable thing she had cooed as a toddler, something her father clung to through the ongoing fissures of their relationship. Since the divorce, she refused to answer to Nono when they spoke on the phone, insisting she would be fifteen this year, that she had outgrown that childish babble, that her father should call her Sadi instead. Sadi was her home name, the name her mother called her, a diminutive she shared with half of the girls in Botalaote Ward, a name heralding the women they would grow into. She supposed it was sufficient, this sign of the immutable and unimaginative love her mother shared with the other mothers of Botalaote Ward.

At eight, she had spent hours with her forefingers stuck in her cheeks, a valiant effort to poke dimples into her face. What a waste those childish hours had been; her fingers were too feeble against the genetic material that had conspired to create her face. But no longer was she a child. She was rising fifteen and in possession of a new determination and a new taste for symbolism, such as: a winter break from school was a prime time for transformation, the bleakness and cloister of the season akin to a hibernation, which was basically what her school break would have been, had her mother not forced her to spend three weeks at the ploughing lands, insensitive to how her only daughter’s skin would fare under the deceptive winter sun. Sadi had worked and worked and her skin had darkened and darkened, and now, though she and her mother were returned to Serowe, Sadi had only a week in which to attend to her complexion, and so she washed and exfoliated and brightened, all in an effort to moult and pupate and arrive at school sleek and self-possessed, novel and enigmatic, someone of her own invention.

She had been trying out a new name. Gigi. Call me Gigi. I am Gigi. In her notebooks: Gagontswe ‘Gigi’ Kaisara. GG Kaisara. Scribbled in her copy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Her Tricolore Troisieme, her IGCSE Modern World History, 3rd edition.

Another thing: she had just finished reading Steve Biko. Consequently she sat at her dressing table, a plastic bag open on her lap, full of the hair that she had just scissored off her head.

‘I must to the barber’s,’ she chuckled to her new image in the mirror. ‘I am mighty hairy about the face.’ She dusted the hair off her cheeks and her neck and her bare shoulders. Her face was big and naked and thrust into the world anew.

Her mother was pissed.

‘What did you do, Sadi?’ she asked, her fatigue from that morning’s shift at Namola Leuba seeming to lift off her.

The basis of her mother’s anger, Sadi understood, lay in the money her mother had spent on Sadi’s hair all these years. Hundreds. Thousands of pula, probably. On relaxers and conditioning treatments, trims and steams, braids and blowouts, cornrows.

Sadi tilted her head away from the mirror. She knitted her fingers under her chin and smiled sweetly, displaying her new face to her mother.

‘Does it suit me?’ she asked.

‘Does it suit you? You are not supposed to cut your hair yourself, don’t you know that? It is taboo.’

It’s taboo. It’s not permitted. You are not supposed to. That is not the way of the Batalaote.

Younger, Sadi had believed every word her mother uttered, the words weighted with the alchemy of spells. Sadi had been terrified to walk with only one shoe on, lest she be swallowed into a clay pot. She had been afraid to push anything away with her foot lest her laziness show up as later-life barrenness. Many a time she had been coerced into public dancing so her mother’s crops wouldn’t fail. Now she saw that these superstitions were her mother’s own talismans, with which she hoped to hold the disarray of the world at bay.

Sadi regarded her mother’s face: the constellation of sun moles on its surface, eyebrows knitted together in concern, dark lips parted with their next reproach. A face so known to Sadi that it had been eroded of any and all mysteries.

‘Why is it taboo to cut off my own hair?’ Sadi asked. What she wanted from her mother was an answer upheld by reason rather than habit, rather than a lingering fear of tempting fate.

Her mother said, ‘I want you to gather up every single strand of your hair and throw it down the toilet. Every single strand. You hear me? I don’t want any people lurking around to take your hair.’

It had been three years since Sadi was plucked from her government school for her academic gifts and awarded a bursary to attend a private boarding school in the city. Her mother paid neither the tuition nor the boarding fees nor the small living allowance Penny received monthly. This trajectory of Sadi’s life had been so inconceivable that her mother still insisted on a particular kind of vigilance, which included ensuring that no visitor could collect any vestiges of Sadi’s body—not her nail cuttings, not her shorn hair, not the print of her feet in the yard.

‘Sadi, your hair was so beautiful,’ her mother said mournfully. ‘Why did you do this?’

‘Mama, have you read this?’ Sadi held a book up. ‘Steve Biko said we are trying to be white women when we relax our hair.’

‘O-wo-o,’ her mother scoffed. ‘And is he going to marry you, that Steve Biko?’

‘That’s what my hair is for?’ Sadi laughed. ‘To find me a husband? What if I don’t want to get married?’

Her mother gave her the look. ‘What did you say?’

‘Mama, Mum, Mummy.’ Sadi walked toward her mother. ‘Mumsy. Dimamzo.’

She cupped her mother’s face in her hands, watching the dawning of a smile on the older woman’s face.

‘I am just playing, Mummy,’ Sadi said. ‘I am going to get married and give you as many grandchildren as you want.’

Her mother laughed.

‘I am going to fill this house with grandchildren,’ Sadi said, flinging her arms wide. ‘So many babies. Babies everywhere. We won’t know where to put them. We will be crushing them under our feet. There will be babies in that wardrobe, babies in the oven. Babies clinging to the ceiling, babies squirming under this bed. Babies e-very-where.’

‘Dear God, for whom I do so little,’ her mother said. ‘What kind of girl is this?’

~~~

- Gothataone Moeng was born and lives in Serowe, Botswana. She was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Fiction, a Summer Workshop scholar at Tin House, and an Emerging Writer Fellow at A Public Space. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in American Short Fiction, One Story, Virginia Quarterly Review, A Public Space, Ploughshares and Oxford American. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Mississippi in the United States. She is currently at work on a novel.

~~~

Publisher information

‘A terrific collection’—Monica Ali, author of Brick Lane and Love Marriage

Full of heart and humour, Gothataone Moeng’s first collection, set between the rural village of Serowe and the thrumming capital city of Gaborone, captures a chorus of voices from a country in flux.

Meet a young woman who has worn the same mourning clothes for almost a year, and a teenage girl who shies away from the room where her once vibrant aunt lies dying. Elsewhere, watch as a younger sister hides her romantic exploits from her family while her older brother openly flaunts his infidelities, and a traveller returns home laden with confusion and shame.

Moeng, part of a new generation of writers coming out of Africa whose work is exploding onto the literary scene, offers us an insight into communities, experiences and landscapes through these cinematic stories peopled with unforgettable female protagonists.

‘A good short story is a bit of alchemy, showing us so much in so few pages. Gothataone Moeng’s debut collection does this over and over.’—Rumaan Alam, author of Leave the World Behind