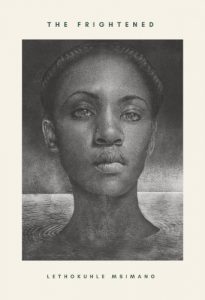

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Frightened, the debut novel from Lethokuhle Msimang.

The Frightened

Lethokuhle Msimang

Karavan Press, 2023

Read the excerpt:

In Memory of Light

In love with the lake

The swan longs to stay longer

But the ice covers the lake

And the swan flies with no regret

—Tsangyang Gyatso, Sixth Dalai Lama

Auguste Rodin had a mistress. A plump and supple young woman—a sculptress. Enchanted by his genius, she lay with him, she lived with him, she dreamed of becoming his wife. Camille Claudel was a student of art, a lover of Greco-Roman mythology. Driven by the works of Donatello and Cellini. She was a welder of copper, bronze, and ore.

And the history of art would pay tribute. They would mention her tumultuous romance, and her gradual descent into madness. And as you walk past Rodin’s Thinker, your thoughts on his lover, on Camille—on a woman carved out from stone, her hands bent over her head, her body curled towards the floor—A Genius Interrupted … you think, there is a storm in the quiet of this old Russian Residency, decorated with the works of Auguste Rodin.

You’re seated by the window looking out towards the lawn. The photographer calls to tell you his daughter has been born. His wife is asleep, exhausted by labour, and the joy in his voice is not for you, and it is not for her. You think about yourself when you think of his daughter. You think of your mother in the delivery room alone. Your father, too afraid to see his first-born son. A year will pass before he musters the courage to see him. My father says he finally came because he’d seen my brother’s photograph—the boy looked like him, it was his son.

My mother wonders why I’ve lost the colour in my eyes. Why I hardly manage to finish a plate of soup. I tell her, ‘Men are not brave, but they are supposed to be.’ She tells me men are ill-prepared and they are frightened.

2

Grace is not to walk on water, but to sink without resistance. I let the darkest of thoughts overcome me. To have a child, I say, is exhausting, and he will run to me, he will fall asleep in my arms. I am nineteen years old, but my logic is sound—he who fucks a child cannot raise one.

3

My father is only a few years older than the photographer. I ask him hypothetically what he would do if I were seeing someone older. He says he doesn’t understand why I would open myself up to that kind of manipulation. I want to tell him that it is me who is manipulative. It was me who threw off my clothes when the old man tried to leave me. It was me who lowered my voice each time I spoke so that he might draw himself closer in order to hear me.

My father says that being with an older man is like fooling a child into eating something she doesn’t want. Like pretending a spoon full of porridge is an airplane flying into her mouth. I tell him that the child knows it is not an airplane. Remind him that children love to play. That the child is getting you to play with her, when all you want is for the child to eat a plate of food.

I let weeks go by without saying a word to the photographer. When I imagine my world without him, I feel my stomach turn and I can’t relax. When I call, he answers the phone hyperventilating, moving further from the sound of a woman’s voice, and the splashing of water, and a child laughing. There is the pitter-patter of hurried footsteps descending a flight of stairs, the buzz of an opened door. He’s on the road now and the cars make it hard for me to hear him. I make out that it’s been too long, that he misses me. That he has been on edge all the while that I’ve been gone. And I’m amazed by my capacity for silence, and its ability to dismantle a home.

4

The photographer has left his large antique camera in my home. It sits in the closet we once used as a dark room. The memory of his hands on my body consumes me. I shift the camera out of my room and ask the butler to help take it down. All this time I’ve had the old man’s camera, he’s rejected every opportunity he has had to take it back. So long as I had it, despite how long it took, he would always have a reason to come back to me. We silently agreed that it would stay. But after seeing my father, I felt an urge to take it back. I order a van to deliver it to his place. I arrive to find the same old man—blue jeans, a cashmere waistcoat, waiting at the corner of his street.

I search hard for his despair. I don’t find it. He doesn’t smile so much as he grins, his front tooth still has a brown lining around it … his beard unshaved … a beggar in a fancy vest. ‘Goodbye,’ I say to the old man. ‘Goodbye,’ he says, sharing the weight of his camera with the driver of the van. I wait on the street as they mount a flight of stairs. I look at the old man, he doesn’t look back.

5

Someone asked me once, ‘How do you know when you have been ruined?’ She wanted to know because her father died and she had since found it hard to love on equal ground. I told her no man will ever love her the way her father did. That nothing is as unconditional as a parent’s love. That she’d suffered a great loss of infinite magnitude. That she would never be alright and she would have to find a way to be okay with that. ‘Trauma is an inconsolable wound you have not accepted to be inconsolable.’ I think the point is not to deny our wounds, but to assimilate them.

6

I looked for the old man in everyone. I searched hardest for him in myself. ‘Why do this?’ he said, in response to my pleading. ‘Life is beautiful …’ And I took that to mean he was, wherever that was, better off than here, in this city, with me.

~~~

- Lethokuhle Msimang was born in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. She graduated with a BA in Literary Studies and Creative Arts from the American University of Paris and an MA in Creative Writing from Rhodes University. Her poems have appeared in New Coin, Grocott’s Mail, Hanging Loose, The Paris/Atlantic and Stanzas, among others. She is the author of, Hubris, a collection of poems. The Frightened is her first novella.

~~~

Publisher information

In this lyrical, fragmented novella, Lethokuhle Msimang uses autobiographical and poetic interventions to lead the reader through landscapes of loss and longing, travelling between France, China, Spain and South Africa, to explore the troubled terrain of leaving and finding home.

At once exhilarating, heart-breaking and haunting, The Frightened speaks to the complexity of relationships, the pain of love, the effects of trauma, the necessity and constant work of healing, and the unfulfillable wish to feel a true sense of belonging. It is the story of finding one’s voice amid inherited violence, and the importance of art and creativity in that process.