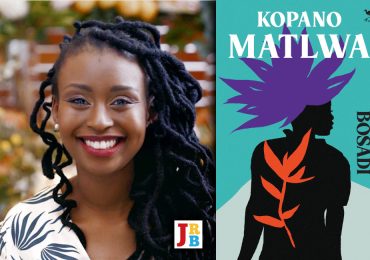

Lebohang Mojapelo chatted to Morabo Morojele about his forthcoming novel, Three Egg Dilemma, to be published this month—fifteen years after his critically acclaimed debut, How We Buried Puso.

Three Egg Dilemma

Morabo Morojele

Jacana Media, 2023

Lebohang Mojapelo for The JRB: Morabo, how have you been doing?

Morabo Morojele: Okay. I’ve been well. Not doing very much. Trying to start another book. To keep myself busy.

The JRB: Oh, okay, so you’re ready to be on to the next one.

Morabo Morojele: Yes.

The JRB: So, congratulations on your upcoming novel Three Egg Dilemma. This is your second novel, with your first, How We Buried Puso, having come out about fifteen years ago?

Morabo Morojele: Yes, that’s true.

The JRB: That is a long time. Why so long and why now?

Morabo Morojele: Why so long and why now? Well, I had been working doing other things. And at the same time, there are a lot of stops and starts, you know, you start writing stuff and then discard it and start again. And I think also, I’ve kind of, I came to writing almost by accident. I mean, I’ve always liked and enjoyed writing and most of my writing has been work related. But I never grew up thinking that I was going to be a writer or that I would try to be a writer. In a sense writing wasn’t something I sought out as such, and therefore, you know, this hiatus between the first book and this one is largely because I suppose I forgot I was a writer. Yeah, I think that’s the main reason.

The JRB: And what do you feel was the difference between the processes of writing the first one and perhaps writing this one?

Morabo Morojele: Well, I think the first one wrote itself, strangely. I think because I didn’t really have expectations around it. You know, I was quite, I suppose, lackadaisical about what it would become and it fared quite well. It got pretty good reviews and all of that, and I think one of the challenges of then going into a second one, I think for artists of all kinds, is that the second offering may be a complete failure. And therefore the process of writing has been much more self-conscious. Although, even with the second book, I haven’t had a book that doesn’t have an outcome at the beginning. In a sense, it also wrote itself because I didn’t have an outline, I didn’t know where to go and it just became what it is almost by accident.

The JRB: When I first heard about Three Egg Dilemma, it was through Jacana [Media], with [publisher] Bridget [Impey] saying, I have this book and we’re looking for a good editor for it. The writer seems, to be kind of being, trying to be selective—and what she did say to me was, basically, that you were looking specifically for a black editor. What was your reasoning behind that?

Morabo Morojele: Well, I think it’s because there’s a reality of having different experiences as black people and white people. Increasingly, of course, people are living more integrated lives in South Africa and Southern Africa, but nevertheless, there will be a history of experiences that a white person may not understand. Even things like language, the use of language, which a white person may not appreciate and may, for example, in editing, change the language in a sense to almost make it ‘proper English’ as opposed to a ‘dirty’ English that people for whom English is not a first language might use. So, I think it’s really for those two reasons, one because of shared experience and two, a sense of closeness around language and the use of language, which a white person may not have.

The JRB: Yes, I think I understand that. We do have, I think, among black people, English that is perhaps different from what would be considered ‘formal’ English. But also, experiencing the publishing landscape, especially in South Africa, it’s still white dominated. So while having a black editor might make a difference, how does race colour your experience within publishing in South Africa?

Morabo Morojele: Well, this will be only the second thing I will have published and therefore I don’t have anything to compare with. I have no other publisher to compare to my current publisher, Jacana. My experiences with Jacana were good. Have been good with the first book, although, as I’ve said to them, perhaps I shouldn’t say this here, maybe you might edit it out … [laughs] I felt that they could have done a lot more for the first book. It got very good reviews, and I was surprised; in a sense I would have thought they would have given it more energy. But what I’m happy about now is that Jacana seems to be very excited about this book, including bringing you guys, people like yourself to come and edit it and so on. And I have already been marketing it quite a lot, even before it’s published, so I’m quite happy about that. I know there are few black publishers in South Africa, and you know, we won’t name them here now. But I think, of course, they need to be supported and I think they also have to reach out to writers to get as much work as they can. You know, in a sense, fight the battle that needs to be fought. There are probably perceptions of black publishers, probably issues around access to where relationships happen, writing happens. So good luck to them, good luck to black publishers. My obligation to Jacana is not until the day I pass away, so in time, who knows? I might well try and support black publishers through writing I might do in the future.

The JRB: To talking about the book, Three Egg Dilemma. You create this landscape, you create this country that is quite familiar and there’s a lot happening. It’s a combination of the ordinary and the mundane, while in this larger space of civil war. Lots of violence happening around. You don’t mention places. You don’t mention the names of the country or the city. I’m assuming it was deliberate.

Morabo Morojele: Well, it was deliberate mainly for the reason that the events that occur, or which I describe in the book, have happened to a degree. But in a sense, they’re not rewritings of events. How do I put this? The writing is not a portrayal of real events, right? I steal a little bit from things that might have happened and then, of course, imagination will then exaggerate them, colour them and so on and so forth, and therefore to have suggested that these events happened in a place would, I think, be a bit of a lie. I’m not sure I’m making myself clear. That I will be telling stories about a place that never happened.

The JRB: So, we can’t, or we’re not allowed to, assume it’s Lesotho?

Morabo Morojele: Of course you are. That’s where I live, most of the time. But in a sense, maybe one of the problems of naming places is that we then bring our knowledge of those places with us and therefore might react to the stories differently. If I know it’s a story like this one, which isn’t located anywhere, I’ll take the story for what it is and will read it for what it is. I’ll try and understand it or respond to it for what it is, without, in a sense, tying myself metaphorically to the place. If a place is named then I would perhaps spend some energy travelling to that place to try and locate the story and that might colour it. I’m not sure I’m very clear, but something like that.

The JRB: Yes, I understand that. You would have to become familiar with the particular place you’re writing about and represent it well and accurately. So then, what is it that you were trying to represent with that deliberate absence of a name, or not naming?

Morabo Morojele: I think, globally, the pandemic. Although very strangely, I didn’t think about the pandemic throughout most of this writing. And in fact, a lot of it happened before the pandemic. But it was really interesting that I found as I was writing it, particularly towards the end, much of the book might be a metaphor for the pandemic, in the sense that most of the key characters find themselves isolated. Society seems to have shut down and so on and so forth. So it might be a representation of people’s lives under lockdown, as it were. But I think also it was because of the violence and the degradation, and the ways in which some of the characters are degraded, and the levels of poverty, and all of that. It is, to an extent, a global story. In most corners of the world, apart from the most developed parts of the world, there are probably people, places, incidents very much like the ones I’ve tried to describe in this book. And therefore hopefully it might be universal in that sense, and perhaps that’s one reason also that I might not have named Lesotho as the place where I live, which I’ve described to a large degree without naming. My point is, somebody could copy this or, having read this book and once this book is published, ask ChatGPT to reproduce a book very similar to mine but located, say, in India. And I don’t know too much about how it works, but that story could in a sense be located anywhere.

The JRB: The main character of the book is our dear friend EG Mohlala. A very sad and lonely character who feels very sorry for himself. And we have this beginning where he encounters a ghost, ‘Mota’s ghost, and this supernatural being weaves throughout the text. We begin with it and then we end with it, in a way, as well. But by the end they have quite a familiar relationship and intimate knowledge of each other, as if ‘Mota is part of Mohlala in some way. What does the ghost mean in this story? Where is the ghost taking us?

Morabo Morojele: I don’t know. At one level the ghost embodies evil, I suppose. And therefore he always seems to, I try to write him to appear just before something terrible happens, when people lose their lives or whatever the case may be. So in some sense it is a representation of that. Second, I think the ghost forces some of the characters, particularly EG, who is of course the narrator, to begin to think about the world beyond. Beyond the mundane, beyond daily life. Life lived from day to day. To think of it from a much deeper perspective. Because, after all, a ghost is not real. Or is it? But if a ghost does appear, I think it would force you or anyone to think about their existence in a very different way, or search for more meaning in the way they live their lives. So I think that’s the purpose of the ghost. And you wouldn’t believe me when I say I wrote that part of the ghost ten years ago. Yeah, and then edited it and then cut, and stopped writing for a few years and started again. And in a sense, because I was stuck with the ghost, I had to then, I just sort of automatically decided to insert the ghost at different stages of this story. And when I started writing in earnest, I didn’t know where it was going to go and when it was going to end. But I think it became a useful device. Sometimes when I didn’t know where to go I would just insert the ghost, in a sense it was a prop. It became something I could bounce ideas off and write activities around and so on and so forth.

The JRB: That makes sense. If you started the story of the ghost ten years ago, it became very much a natural part of the book. And I remember in the editing process, I was asking myself, what’s the story with the ghost? Why does it go away for so long? He needs to come back! The ghost also connects with the other character central to the text, Puleng. She mentions seeing the ghost, which none of the other characters do. Puleng, who comes in and disrupts EG’s life from several perspectives. He falls in love, he is a bit confused, he has someone next to him, which is something he hasn’t had in a while, some form of intimacy or closeness. He doesn’t have family. Puleng is also the one other character we have insight into. There are maybe two places in the novel where we get to see and hear from her perspective. But she appears as Puleng, and then as she starts to work and live her own life she becomes Pearl. What is the difference between Puleng and Pearl?

Morabo Morojele: [Laughs] That’s a very good question. The difference is Puleng is given, Puleng is unmade. She is what she was when she was born. Whereas Pearl is full of ambition. Has goals for herself and actively pursues them. And understands full well that the world is made up, that navigating the world is very much about your image or the way you portray yourself, and that therefore to change her name from Puleng to Pearl makes it easier for her to interact with foreigners, or white people at the hotel where she works. We, of course, as Africans know that very well. Very often in the past people would be given names randomly by white managers that their patrons could call them. So in a sense that’s what that name change is about, somebody seeking a future and therefore changing her name—from admittedly not a difficult name. I mean, Puleng is not a difficult name but it’s slightly more pronounceable. At the same time, I suppose in the word Pearl is an ambition to be a thing of beauty. To be a rare thing. And in as much as she’s still naïve, she’s relatively rural in terms of her upbringing and so on, she still has dreams about what her future could become, and therefore names that future in the metaphor that is Pearl.

The JRB: And then these two characters who live in the same space begin to find a way around each other. But then Mohlala sort of messes it up when he comes on to her, in an unexpected way. And I’m wondering, I think I still feel, I don’t understand that encounter. I didn’t realise Mohlala was in love with Pearl. Was he in love with her?

Morabo Morojele: Yes, I think so. Because as you rightly said, he hadn’t had intimate relationships for a long time. The relationships he had were with the fractured many he hung around with at the bar, long relationships but without the intimacy of the kind a man might have with a woman. Or, you know, a relationship partners of whatever gender might have with each other. And therefore I think, yes, he did fall in love with her. But I also think somehow, their relationship could never properly materialise. One, he was much older than her, second, she was innocent and three, he was fixed in the way he lived. Whereas she was young, beautiful and had intentions for herself. And as sad as it is, I think for a lot of people there is that loneliness. They live their lives alone and in loneliness. And it is what it is. I think that is what that relationship is trying to show.

The JRB: Yes, I think it makes sense in that way. I was very keen on the way they began to find a way to live together and thought perhaps they found, you know, a different kind of love or way of being intimate. So perhaps I was disappointed and uneasy to a certain extent, because Pearl is really just longing for a place of safety: growing up in an unpredictable home, being abused at the hotel, becoming homeless. She never seems to find this safety, and it felt like the closest she got was during that brief period with EG.

Morabo Morojele: That’s very true. And yet while that was a place of safety for her, if she had simply stayed there, that’s all it could ever have remained. That’s all it would ever have been. She needed, really, to get away, and I think she needed to get away to the hotel, to work, to a different world from that very innocent, static and predictable world of EG. The hotel where she works as a waiter provides exactly that opportunity, and at one level she achieves a lot simply by being there. In the end, she achieves something simply by working at the hotel.

The JRB: Yes, true. And, like you said, she was ambitious. I want us to go back to EG’s static world. I mean, he has a few adventures, but then seems not to want to try anymore. So he has this experience where a young boy comes up to him and then he is told by the caregiver of this young boy that he is his child, and without really investigating, he takes him on as his son. The mother does the same thing. And then there is disappointment when they find out that it’s not really his son, and yet he still keeps a photograph. He still reminisces about it as if he actually did have a son at some point. Grieving about how there’s no word for a parent losing a child.

Morabo Morojele: Well, perhaps in a similar way that the Pearl is symbolic of hope for Puleng, for EG, even though the boy was not his son, the image of the boy, or the idea of the boy, is of what he could have had. He could have had relationships, he could have had a son and therefore a family, because he’s a character without family. Here’s a question: if I had been in that situation, would I have stomped on the picture of the boy and burnt it in some kind of ritual because I am angered at having been duped? Perhaps I might have kept it, just to say, oh well, how lovely it might have been if that boy had been my son. And, in a sense, it’s a reminder of the hope he might have had of having a child, and therefore a family. Yeah, I think that’s what I’m trying to say, yeah.

The JRB: I have to say, one of my favourite characters is Mkhulu, who seems to be quite a sturdy character, very consistent, very present throughout the text and in who he is. Even when there’s the big unrest and they help each other find a place to stay and to survive afterwards. Although he seems like such a fragile old man, he makes it through. There are two things happening that I feel are represented by Mkhulu, in a way. There is steadiness and consistency throughout the text. And at the same time it’s a very fragile space in terms of peace, in terms of violence, in terms of what’s happening. But yeah, I like Mkhulu.

Morabo Morojele: More than Sticks?

The JRB: Well, yes, more than Sticks. Sticks is funny. Sticks is hilarious. Walks around with the scale, you know, concerned about people’s health. I like that.

Morabo Morojele: He’s not actually concerned about their health. He just wants money.

The JRB: Well, his ruse is clearly working! Sticks and Latrine offer so much humour, you do have a lot of comic relief through those characters. Who do you think your favourite character is?

Morabo Morojele: I think Sticks. Because he has fallen down. He is a bit of a jester. He’s a bit of a fool. He’s loyal and a survivor.

The JRB: And he picks all the good songs on the jukebox.

Morabo Morojele: Yes, he plays all the great music on the jukebox. And coaches the Bible.

The JRB: Yes, and very adept, and likes to read it out loud.

Morabo Morojele: And he’s always on point. I really enjoyed him and I wish I could have enriched him a little bit because he’s quite a likeable rascal, I think.

The JRB: Yes, I think so, or dislikable sometimes [laughs]. But anyway, I would like to ask you about the dilemma. Have you solved the dilemma? Is it two eggs or three, or are you just still in between the eggs?

Morabo Morojele: It’s three eggs, I think. Basically the whole title comes from a real life experience I had. I think it’s really mundane, but there it is. I was really down in the dumps and I would literally eat two eggs a day with bread. And then I’d cook myself something in the evening. Something relatively light because I didn’t have much money. And so I had this ritual of two eggs every day, and I knew that, you know, after the third day, I’d go and buy another six eggs. And so it would go. Then one day I had four eggs left. I had eaten two the previous day so I had four left. I was taking two out and one fell and I couldn’t save it, I think I stepped on it. So I was left with three eggs. Now in a sense, the question then became what to do with these three eggs. Whether I should have two, as usual, whether I should have one, or in fact whether I should just have all three and see what happens to me come tomorrow. And that’s the dilemma. It’s about choices. What are the choices we make. Of course, people would respond to that question differently. Some would say no, I’m taking one today, bad luck for me. Some, on the other hand, would say I am having all three, and so on and so forth. And I suppose it’s a question of temperament and what have you. But that’s where the title comes from, Three Egg Dilemma. And the dilemma in the end, I suppose I shouldn’t be saying this, but the dilemma confronts Puleng or Pearl and it’s not the narrator’s dilemma. It becomes about Puleng and what choices she makes towards the end of the book.

The JRB: Yes, in her final monologue she says she wants them all?

Morabo Morojele: Well, I think she chose the three eggs.

The JRB: Could you give us a little bit of insight into the next novel and what’s coming up?

Morabo Morojele: Okay. The next one is actually not a novel, it’s a collection of short stories. One story I had written and was originally part of Three Egg Dilemma and I think between myself and the publisher we thought it might not work with the novel, which I agreed with, I came to see. So I’m going to restructure that so it can stand alone, because there is a story there. The story about Alice, if you remember? The whole trip to Botswana from Lesotho to go and see a girlfriend. Arriving to find that she’s getting married …

The JRB: Yes, that was such an amazing part of the novel, by the way. It really felt like the only time we encountered EG taking a chance and doing something, you know, proactive. And it just didn’t work out. And then I don’t think I ever saw him take a chance again.

Morabo Morojele: So that could be one of the stories. It’s almost written. The other stories are very interesting. I was ill, very ill, earlier last year, to the point of being hospitalised and so on, and I was unconscious for a while and surgeries and what have you. And during the course of my illness I had psychosis, and apparently a lot of people who are very ill become psychotic. So I didn’t remember many things that had happened around me, many, many things. Like, important things. For example, I was transported by ambulance from Lesotho to South Africa, to Johannesburg. I have no recollection of that whatsoever, although I was awake. So now, during my psychosis, I had amazing dreams. Really, really amazing things that I am currently in the process of writing.

I would also really like to write about my journey in music; I have worked with a lot of famous artists over the years, and there’s a lot to share there …

The JRB: Well, thank you very much for your time, I look forward to your book launch and finally getting to. meet you in person.

Morabo Morojele: Yes, likewise.

- Lebohang Mojapelo is an editor, writer, researcher and poet based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.

6 thoughts on “‘Why so long and why now? … I suppose I forgot I was a writer’—Morabo Morojele chats to Lebohang Mojapelo about his forthcoming novel Three Egg Dilemma”