Sindi-Leigh McBride reviews Koleka Putuma’s Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In, a joy to behold even when the subject is devastating.

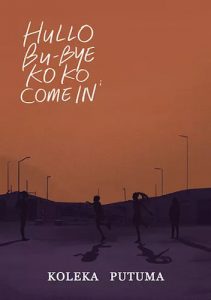

Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In

Koleka Putuma

Manyano Media, 2021

I’ve shied away from poetry because it makes me nervous. I have no training to steady myself, and it tends to have the opposite effect on me from the one I assume was intended. But every once in a while, a poem or poet steadies my nerves while rattling my spine.

Cue Koleka Putuma.

I first came to her work during the 2018 drought in Cape Town: science seemed to offer no solution to my climate anxiety and writing was the only solace; as I penned an essay on waterworks in the city, Putuma’s poem ‘Water’ offered me a grounding prayer; still does today. I greedily sneaked peeks at the rest of the collection, Collective Amnesia (2017), one poem at a time, while visiting men keen to demonstrate their wokeness on their bookshelves. They thought I was there for them, shame. Something stopped me from getting my own copy, perhaps I subconsciously already suspected the effect the poems, when read in totality, would have on me. Bongani Madondo reviewed that collection in first edition of The JRB (‘Portrait of the poet as a young genius: Bongani Madondo reviews Koleka Putuma’s Collective Amnesia’) and wrote:

There’s much to adore in a young poet whose work distils wit, social commentary, and abstract magic, yet still comes across as unable to show off. Her aloofness on page and in person is a reflection of an artist who suffers no fools. It is not being rude. It is not ‘knowing her value’ as a woman, child, sister, sibling, artist, and so on ad nauseam, at this time when identity and likability are tradeable commodities. It is, instead, an irresistible detachment that at the same time renders heartfelt feeling.

I saw that ‘irresistible detachment’ live when I met Putuma for the first time in April 2022, at a workshop that I co-organised with a friend and colleague from Basel, Julia Rensing. The day involved a guided tour of the historic, iconic Jagger Library building at the University of Cape Town, which tragically burnt in a devastating fire in 2021; followed by a tour of Of Smoke and Ash, a commemorative exhibition curated by Duane Jethro and Jade Nair at The Centre for Curating the Archive. During both activities, Putuma stood apart. While everyone made small talk about the loss of the library, she stood out for her silence. Not rude, reticent. After the tours, Atiyyah Khan played a vinyl set, a deep listening session of what she calls her ‘library records’ because of how much she has learnt from them. The artists and academics participating in the event sat in silence, making notes or sketches, processing all that we had seen and heard, but Putuma walked to the front of the room (the set was held in the Old Anatomy Lecture Hall at the University of Cape Town, a wood-panelled blast from the past) and stretched out on the floor. She listened to the set from there, eyes closed. Those quiet moments of ‘this is the best way for me to do it’ self-assurance will stay with me forever.

Soon after, the writer Bongani Kona, who also participated in the workshop, gave me a prized collection by American poet Claudia Rankine and it was thanks to this gift that I returned to reading poetry after a years-long drought. Rankine writes:

‘Then the voice in your head silently tells you to take your foot off your throat because just getting along shouldn’t be an ambition.’

Koleka’s latest collection, Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In, is that voice. Not just for me (though it has been that too) but in many ways for a country that she is hurt by and hopeful for. The title of the book is inspired by a South African phrase made famous by the legendary musician Brenda Fassie in her 1992 song ‘Istraight Lendaba’, and builds on the themes she explored in her first book, Collective Amnesia, an arrow straight to the heart in confronting the legacies of black femme erasure from society as well as in the arts. The success of Collective Amnesia, a bestseller that has sold over ten thousand copies and has been translated into eight languages around the world, saw Putuma perform for audiences across the continent as well as in Europe. Putuma says:

In writing Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In, I wanted to reflect on my personal experiences of travelling and performing outside of South Africa and more specifically, Europe. I wanted to understand different aesthetics and forms of memory, documentation, performance, hyper-visibility and erasure. I wanted to look at how those things frame our understanding of women in the archive, legacies of archiving, celebration, fame, culture and black women on and off the stage.

In the Foreword of Collective Amnesia, Lebogang Mashile wrote: ‘There are books that rip open the heart of their time.’ Putuma doesn’t rip things apart in her sophomore collection, but neither does she suture. She calls attention to common keloids: sometimes urgently, bursting out in a torrent of feeling; sometimes laconically, the grace always in her restraint. In all cases, her handle on language is palpable, as is her diligence as a researcher and social observer. This makes her work a joy to behold even when the subject is devastating. Take for instance these snippets from ‘I saw the best minds of my generation’:

who asked why? more often than they asked what?

who said ‘it’s the residue of colonialism for me’

…

who raised back children who idolized elsa and peppa pig

and bought those same children black dolls with afros and

shweshwe alice bands

…

who lived as if they were invincible

who were treated as though they were invisible

…

who held nervous conditions with the quiet violence of dreams

who sought to unlearn their nervous conditions

and the parts of their past that did not heal

or howl

it hurt

it hurt

it hurt.

You read a poem like that and the uncanny feeling of ‘wow, she hit the nail on the head with this one’ pervades, but it’s the epistrophe, the repetition of words and phrases at the end, that really drives the point home. It really does hurt, to bear witness.

I worked through Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In while plodding to the end of my PhD in freezing Switzerland. The poems drifted to me and settled on my shoulders like snowflakes. Sometimes I read them first thing in the morning before going to the library to churn out pages; sometimes I read them during my evening bath. Each poem felt like a portal to home that lifted my foot off my throat and motivated me to strive through the loneliness and drudgery of migrant academic life. Sometimes, this was because their thematic relevance was eerily timely, like two poems on citations that I read a week before I was due to submit a paper on the topic. I was at a loss for how to start until this:

the draft begins with a

black woman

backspace

the draft begins with

a citation credited by a

black woman

credited to someone

nonblack (†)

Putuma has a light hand when dealing heavy blows, delivering gut-wrenching work, bearable because of that ‘irresistible detachment’. For example, ‘these people’ takes stock of the disproportionately high number of writers who commit suicide (and to this list Putuma adds an addendum of ‘the disappearances that do not go on record as sirens or signals’) while ‘youdidntknowyouwouldfallinlovewithanalcoholic’ breathlessly traces the pain of proximity to substance abuse. ‘you built this country with your movements too’ brings much-needed visibility to the role of women in the anti-apartheid struggle with tight tributes that include identifying footnotes [given here as endnotes, for HTML formatting reasons—ed.]:

kept in solitary confinement for a year without visitors or reading

matter, charged and sentenced for 5 years for belonging to a party

that only served you (1) because you served it in return

The book is divided into four chapters, dealing with subjects related to history, the erasure of black women from the archive, and more personal poems, where Putuma resuscitates the stories of women in her lineage who have had an influence on her life. Peppered between the chapters are quotes from inspirations as diverse as popular singer Makhadzi to Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, reminders that this is not an artist who works alone—she is well-supported by those she honours. As she says:

I wanted these excerpts to serve as a conversation between the poems and an archive of sorts—an archive of black women (living and dead) who are looked at, celebrated, uncited, erased and exploited. I wanted to make visible the words of black women who have had to navigate the complexities of a constant gaze that often renders the ‘looked at’ invisible. In my quest, I wanted to further understand and challenge my own methods of citation, documentation and seeing—and in doing that, invite others to do the same.

Also worth mentioning, this book was published by Manyano Media, a multidisciplinary creative company founded by Putuma in 2019 to create employment and development opportunities, as well as platforms for independent poets, playwrights, theatre directors, set designers, costume designers, lighting technicians and editors in South Africa who identify as black, queer and woman. ‘let us count the ways’ hints at some of the gravitas behind this:

at the panel discussion

the moderator asks

how it feels to be a bestseller

you ramble about

gratitude

the integration of imagination and

the cost of books in this country

you are too ashamed

to also mention

that there have been times

you could not afford your own book

that it has taken you

not fully owning your story

to know the cost of your story.

In 2020, Manyano Media created a relief fund to assist a number of black, queer women theatre practitioners and poets with subsistence grants during Covid-19. The relief fund has now been further developed into the [BLACK GIRL LIVE] fellowship, an accelerator and mentorship programme that empowers black and queer women storytellers. This is an artist that knows not only the value of her own story, outside of neoliberal estimations of value in a global market of book development or marketing, but also cares for the protection of others’ stories.

And in a world where black queer women artists and their stories are so often eviscerated by erasure, Putuma’s work rightfully continues to be recognised. On 1 December 2022, she was announced as the inaugural recipient of the Standard Bank Young Artist Awards 2022 for poetry.

Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In includes numerous poems all titled ‘after Ntozake Shange’ and spread throughout the book, an ode to the American playwright and poet best known for her play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1975). For the moment, for the no-longer-emerging maverick who is coming for all her flowers, this excerpt is perhaps most apt:

after Ntozake Shange

for

black

queer

women

artists

who have considered receiving the lifetime achievement award

when the emerging is enuf.

(†) The citations are the real genius of the book, and a magnificently triumphant answer to Canadian geographer Katherine McKittrick, in her chapter on footnotes in Dear Science and Other Stories (2021), where she reads ‘in-and-with black studies to honor those who have shared their intellectual and political energy with me—their effort—in myriad infrastructures, feelings, texts, stories, exchanges’ to ask: ‘What if the practice of referencing, sourcing, and crediting is always bursting with intellectual life and takes us outside ourselves?’

(1) Frances Baard

- Sindi-Leigh McBride is a researcher, writer and PhD candidate at the University of Basel. Follow her on Twitter.