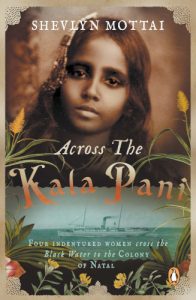

The JRB presents an excerpt from Across the Kala Pani, the debut novel by Shevlyn Mottai.

Across the Kala Pani

Shevlyn Mottai

Penguin Random House, 2022

Sappani, Lutchmee and Seyan had been assigned the room at the end of a line. They stepped inside. Sappani reached for their lantern and lit it, and it immediately cast strange forms onto the walls.

The room was bare and reeked of stale ghee. The walls were blackened; there were remnants of a fire in the centre of the floor. A small glass square serving as a window let in some light.

Sappani laid out their rations in a corner, and unrolled the bedrolls.

‘You may want to stuff some cloth under that door to keep out the snakes and mice,’ Kuppen called helpfully as he passed.

It was getting darker, and they could hear the sounds of people bustling about preparing the evening meal. The aroma of frying food reminded Sappani that they needed to eat. He set about building a fire outside, not wanting to fill their room with smoke. Lutchmee decided what vegetables she could cook quickly, and looked through the spice dhaba Sappani had given her two months previously, when they’d first boarded the boat to cross the Kala Pani.

They had a simple meal of aloo gobi and rotis around the fire. Lutchmee watched her new husband eat. ‘Good, really good. Such soft roti, too,’ was his verdict.

Lutchmee felt her spirits soar. It wasn’t the best curry she’d ever cooked but she appreciated his response.

Once the family had eaten, Lutchmee put the dirty pot and plates in a pile, then picked it up and followed what they saw other families doing.

In the washing-up area, water came from a pump, presumably supplied by a local dam or river. While Lutchmee washed their dishes, Sappani filled buckets of water and poured them into a large tin drum that stood outside their room. This water would be boiled for drinking and be used for washing themselves.

Finally, the idea of a proper wash of their bodies was very appealing.

On the ship, ablutions had mostly been a case of wiping themselves down with a wet rag dipped into a small dish of water.

Sappani filled a large pot with water and stoked the fire so that it would boil quickly. Once it was heated, he carried the pot of boiling water to the washing stalls at the other end of the line, next to the latrines.

Roughly rectangular, the concrete walls of each stall were hip-high, to give the bathers some privacy, while in each there was a small stool to sit on and a large galvanised dish to pour the hot water into, then the cold water could be added with water from the pump.

They decided that Seyan should be washed first, as his eyes were already starting to close. Sappani prepared the bath, feeling the water with his hands until the temperature was right. Lutchmee, who’d brought the little boy, along with a bowl, some soap and rags, removed Seyan’s clothes. Under Sappani’s close gaze, Lutchmee felt nervous but she’d seen this being done before: she was going to give Seyan a leg bath the way she’d seen babies in India being washed.

She hiked her sari up to her knees and sat on the small stool. She then stretched her legs out in front of her, and placed Seyan, tummy down, on her shins, in this way using her lower legs to hold him in place and freeing both her hands. She dipped the bowl into the warm water that Sappani had prepared, and poured it over the child’s back.

Sappani handed her the piece of soap, and she used it to wash the little boy, gently rubbing at his skin. Once his back was washed and rinsed, she turned him over and repeated the process on his front.

Not used to such a thorough bath, and also overtired from a day full of unaccustomed people and activities, Seyan began to cry, but his father reassured him and he fell quiet again. Lutchmee then washed his hair, careful to screen his face with her hands so that the soap and water didn’t go into his eyes. Finally, she wiped him down, pleased with the results: his cheeky little face seemed brighter, and his damp, dark hair smelled clean.

She stood up and was ready to take him back to their room to dress him for bed, when Sappani offered to relieve her. He’d noticed that some other women had arrived at the washing stalls, some of them standing sentry while the others washed.

Lutchmee gave herself a quick but thorough top-to-toe wash, using the warm water Sappani had prepared. It felt so good to be properly clean again. Then, dressing herself, she went back to their room and let Sappani know that it was his turn.

Later, despite being very tired, many of the newcomers assembled in the yard. It was a strange new world, and some of the Indians felt curiously insecure in the absence of the many sounds of the ship, so they sought comfort from each other. A night bird called, the crickets were chirping and there were the low croaks of frogs.

Some of longer-time resident Indians gathered with musical instruments.

A man with a greying beard and grey hair played a mournful tune on his harmonium. Two women began singing bhajans as their children darted around them.

The women had also gathered, good-humouredly scolding the children who were dirtying themselves after their baths. A mother pulled and tugged at her daughter’s hair as she tied it into two shiny, thick plaits.

The men smoked their beedis and idly chatted. Someone produced a hookah and soon a sweet scent filled the air.

A deck of cards was shuffled and four men began a game called thunee.

It turned out to be fun to watch; one of the players explained to the small audience that the card game had been created by Ramsamy Naidoo, who’d been the sirdar on the state back in the 1870s, well before the time of the Rouillard brothers.

Lutchmee took the soundly sleeping Seyan back to their room and placed him lovingly in the bedroll. She climbed in beside him and sleep came quickly to her, despite her wanting to wait for Sappani to return.

In a few minutes her and Seyan’s breathing fell into the same pattern.

Sappani sat outside among those who had lived here for a while, listening, not talking, eager to get as much information as he could.

Finally, an hour or so later, each family drifted back to their separate rooms.

It was still dark when a bell rang, and the Indians were woken by the rattling sound of the sticks used by the sirdars as they walked down the lines, dragging them across the room doors.

Leaving Seyan and Sappani dozing, Lutchmee got up to carry out her puja. She hadn’t prayed since she was in her village but something about the previous night had filled her with gratitude and she wanted to start the day thanking God for this new life.

Dishevelled and sleepy, in their faded saris, other women began arriving at the washing area, carrying lamps and candles. Lutchmee joined in with them in their prayers. She arranged flowers on trays with water in a lota.

Then, facing east and drawing her pallu over her head, she chanted with the other women as life began to stir in the barracks.

By the time Lutchmee returned to their room, Sappani was ready to leave; they had agreed that she would look after Seyan, while Sappani went to work. She made up a tiffin for him and watched from the doorstep as he joined the other men, the bell clanging loudly to signal the start of the work day. It was 5 a.m.

When Seyan woke, he was hungry. Realising this was the first time she’d been completely alone with the baby, Lutchmee fed him then sought the company of others.

In the washing area, the women were washing clothes. Their bangles chimed in unison as they soaped the items, then whacked them against the concrete block built in for this purpose. In an array of buckets and dishes and tin drums, they rinsed their families’ laundry while the conversation rose and fell—Hindi, Tamil, Telegu, they all picked up

words here and phrases there, and began to weave these into a sense that they understood.

Lulled by the chatter of the women and comforting sounds of clotheswashing, Lutchmee was at ease. Even though it was early, and supposedly the cold season, the African sun was already hot. The water was cool and refreshing, and she repeatedly anointed her face and neck with it. Standing upright to relieve the mild ache in her back, she allowed it to spill out of the bucket and onto her sari and bare feet.

Seyan splashed happily in the puddles collecting around their feet, and Lutchmee felt her soul well up. It wasn’t just the value of the chores she was doing, or the warm feeling of responsibility it gave her, but the knowledge that she was needed and cared for by innocence itself. She smiled at Seyan and he gurgled back at her. She was beginning to feel as if the world was welcoming her back into it again.

The women who had been there longer offered up useful advice that was greedily taken in. They spoke about the journey they had all made across the sea, where to get provisions, which sirdars to look out for, the master and his wife.

There was also something unspoken that passed between them all. As if with an invisible thread, they were bound together by their circumstances. While they were hopeful that they would be able to survive this new world, there was also fear and some regret.

But as Lutchmee hung up her family’s washing on a line tied between two large mango trees, she couldn’t help but feel optimistic, and she allowed the happy sensation to flit about in her mind for a while before it settled again. She desperately hoped that, not far away, Vottie and Chinmah were also feeling at ease.

~~~

- Shevlyn Mottai works as a deputy headteacher and English teacher in a secondary school in England. Born in Pietermaritzburg in 1976, she descends from Indians who were part of the diaspora to South Africa, her forefathers having arrived in Natal through indenture in 1906. She has taken several courses in creative writing and has published poetry and short stories in competitions.

~~~

Publisher information

Four indentured women cross the black water to the Colony of Natal

In 1909, four women board a ship in Madras to cross the Kala Pani, the ‘black water’, to Natal. Lutchmee, a young widow, has escaped her vengeful mother-in-law and self-immolation on her husband’s funeral pyre. Vottie, from the Brahmin caste, is an educated girl whose abusive husband tries to hold on to his caste at all costs. Chinmah, heavily pregnant when she boards the ship, is married to an older man as part of an unpaid debt. Dazzling but shy Jyothi is single. On board the ship, the women will form friendships and alliances. They will help each other through trial and trauma, even after they arrive and are separated.

Like many Indians desperate to escape unbearable conditions in their home country, these women are only too eager to believe what they’ve been told: that a better life awaits them in South Africa, where caste doesn’t matter, food is plentiful, and liberty will be theirs after just five years. But the reality of life on the plantations reveals the truth about the crossing: that it is usually a one-way journey, rife with misery, and that the hardship doesn’t end after the ship has dropped anchor in Durban harbour.

The epic stories of these immigrants—the brave, the bold, the kind; the weak, the cruel, the cowardly—are woven into the fabric of South Africa’s Indian population today. Shevlyn Mottai has drawn on her ancestors’ history to highlight the bonds formed between women during adversity, and to celebrate their journeys of tragedy and triumph.