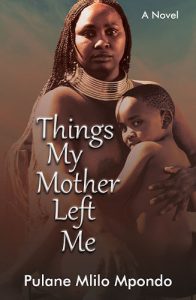

The JRB presents an excerpt from Things My Mother Left Me, the debut novel by Pulane Mlilo Mpondo.

Things My Mother Left Me

Pulane Mlilo Mpondo

BlackBird Books, 2022

Read the excerpt:

It has been two weeks since the bleeding and more than a month since the fire, and now Mlambo is at Thandeka’s gate, on either side of him his brother and uncles. They have come to do his bidding the same way they stood at my father’s gate almost a decade ago; they are here to ask that the woman they had taken return home, as a wife ought to. Thandeka stands on her stoep, blocking me from the doorway. Mlambo calls for Nyaki and she appears from the back of the house, running around its side and straight into her father’s arms, but his eyes are steady on the doorway that Thandeka still blocks with her body. Those eyes are always steady, always planning. I watch him hold my child, unflinching, the child he poured fire onto. Thandeka calls for Speedy to bring a wooden bench and two chairs for the visitors to sit. She waits until they are seated in her front yard before she goes to them, her contempt tangible. With her body gone from the door, I am thankful for the shade that continues to hide me. Thandeka does not greet; she offers no hand to be shaken, no bent knee as sign of respect, no glass of water or cups of tea. She never did appreciate uninvited guests, especially not ones who had conspired to burn her baby sister and nieces on an ordinary Tuesday night.

‘Sizo landa umakoti,’ the first uncle speaks. ‘A wife, a married woman, should not be without her husband.’

‘Which wife?’ my sister retorts. ‘The wife I know was locked in a burning house more than a month ago.’

‘Liyadelela elidikazi,’ Mlambo’s older brother insults. ‘We won’t be insulted by an unmarried woman.’

‘Dikazi? I have bigger balls and better sense than all of you combined,’ Thandeka scoffs as she scans the men in front of her.

I had heard everyone’s voice, everyone had something to say, except Mlambo, who hadn’t said a word. I know my husband. He is a smart man. He knows better than to say the words ‘I have come fetch my wife’. He knows what not to say when the sun is watching. He knows as well as I do, standing in that passage, that his wife and children died in a fire that he put a light to, and that the sun knows it too.

After quiet deliberation, Mlambo, his brother and uncles get up and head towards the front gate. Thandeka comes back inside, pushing past me and calling for Speedy to pack away the bench and chairs. Nyaki runs after her father, crying out for him to wait. At the gate, he waits with arms outstretched for the child he buried in a fire. But before she reaches the gate Nyaki stops short and stands looking at him, quietly studying him and whatever is behind the dark complexion that she inherited. Then, as though the wind whispered something to her, she turns around to look at me. I am, after all, where she truly belongs.

‘You are going back,’ Thandeka says. ‘He wants you back, so you are going back.’ I look at her, stunned, but I know better than to protest. I have always done as Thandeka instructed. The first and only time I disobeyed her was when I married Mlambo. It wasn’t that she disapproved of his lack of schooling, or his methods of making money. It was the evil that Thandeka saw in him, an evil that my eyes were too naive to recognise. ‘There is a darkness in that man,’ she’d said the first time they met. All I saw was the way he loved me.

So, when Thandeka says that I am going back, I know that I will. But there is something in her eyes, a quickness in the way they dart around the room looking for something, which tells me that I am not going back to stay. Thandeka hurries to the kitchen and brings back a fistful of R100 notes.

‘Sisi, what is going on?’ I ask.

‘Get dressed. We are going to Baghdad,’ she orders.

‘The hotel?’

‘Yes. They are coming back for you tomorrow, but before you leave, we must go to Baghdad.’

‘What are we going to do there?’

‘We are going to sisi Nomawhule.’

My body shudders at the mention of that name. It is a name that has not passed our lips for many years, a name for a memory we knew as young girls, a name spoken in whispers in dark rooms keeping the secrets of heavy hearts. Her name belonged to another world, even though her body lived in ours. Sisi Nomawhule spoke to things of the night, things that our eyes weren’t permitted to see. The broken-spirited, the desperate, the aggrieved and the enraged knew her well. She was the remedy to ailments that white medicine could not cure.

Thandeka takes the back seat of the taxi and I follow her in. Its torn plastic covers cut into the backs of my legs, but the muscles in my thighs exhale with relief after the long walk to the taxi rank. I take the coins for the fare from my pocket and pass them to Thandeka, then look out of the window, watching the road turn from bumper-to-bumper traffic to open fields.

‘We are here,’ Thandeka says, shaking me awake. I quickly wipe the drool that has dried at the side of my mouth. It is almost sunset. The sky is orange and the pavement does not burn through my shoes so much. I follow Thandeka up a street where a girl is throwing a plastic ball at friends who duck from it. We turn right onto another street. A teenage girl leans against a wall, touching a man twice my age. On the next street, I smell amagwinya, Russians and chips, and I know that we are close. I remember this scent, and the taste.

Sundays are my favourite time in the city.

The streets are quiet enough for the ancient buildings to tell you stories about the hands that built them, and even to echo the sounds of the feet that walked alongside them long, long ago. The trees hang playfully over the pavements, lending their branches for children to climb, and the sun drapes itself lazily over the buildings to listen to the stories that every brick tells about the South Africa Mandela once believed in.

It has been years since I’ve seen it. A lot has changed, but more has remained the same. The building is not as grand as when my mother cleaned its rooms, but it is still the tall confidant it was years ago. The hotel’s walls are still the same red, but they no longer have their smooth, velvety texture.

Pictures of those who sang in its bar still hang proudly—Dolly Radebe in her long sequinned dress; Mama Africa, regal in a figure-hugging white dress, leans over her microphone playfully, laughing with a saxophonist; and, finally, my mother, standing proudly behind the bar. Although the frames may be skew and their glass coated with dust, Hotel Baghdad refuses to be buried under the perversion of this city. In these pictures it holds onto what it once was, the way I remember it the day my mother brought us with her to see the lady on the seventh floor.

The lift does not work so we walk up several flights of stairs. When we reach the room, the door opens before our knuckles even touch it.

I could not have remembered her face, not in its entirety for I was too young when I first came here. I remember trying to hold onto her features, how wide or long each one was, where one ended and another began, but as soon as her eyes faded, my memory struggled and everything else followed into an abyss. I was too young to take stock of it all, but what never left me was how gloriously black she was. She was not only dark, but also luminous, not shiny in the way babies are when smothered in Vaseline, but luminous in the way the ocean is beneath the moon, like wet tar. Above that was her wild hair, which stood thick and upright as though ready to give a sermon. Her tar skin and indulgent hair are the only two features that never faded and, after all these years, they are the two that greet us first at her door.

~~~

- Pulane Mlilo Mpondo has been published by and contributed to various national and international platforms including the Daily Maverick, ELLE Magazine, Marie Claire and UK Guardian. Her debut novel is Things My Mother Left Me.

~~~

Publisher information

‘I hear them climb onto my roof, the men, they have given up all negotiations with the door. But the roof is no good either, it’s too hot up there, the corrugated iron that covers my home is quick to gather and boast of the heat. That iron roof makes life uncomfortable, it bakes and heaves with the heat, playing musical chairs, making us unwelcome visitors in our own home. That roof is cruel, and now it is burning the soles of the men who are trying to save our lives.’

Things My Mother Left Me is a debut offering that traces the lives of women in varied contexts, women who refuse to be erased by the circumstances that render them invisible. Women who, insist that they not only want to stay alive but to do so on their own terms.

Pulane Mlilo Mpondo challenges the reader to think deeply about the consequences of growing up in the other South Africa, where one is constantly met with the harsh realities caused by inequality, poverty, broken homes, and the inevitable empty promises made every fourth quarter.

With its lyrical prose, Things My Mother Left Me will break then gather the pieces of the reader’s heart. A reminder that a mother’s prayers do not go unheard nor her tears unseen …