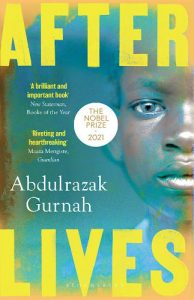

The JRB presents an excerpt from Afterlives, the new novel from Abdulrazak Gurnah, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Afterlives

Abdulrazak Gurnah

Bloomsbury, 2021

Read the excerpt:

1

Khalifa was twenty-six years old when he met the merchant Amur Biashara. At the time he was working for a small private bank owned by two Gujarati brothers. The Indian-run private banks were the only ones that had dealings with local merchants and accommodated themselves to their ways of doing business. The big banks wanted business run by paperwork and securities and guarantees, which did not always suit local merchants who worked on networks and associations invisible to the naked eye. The brothers employed Khalifa because he was related to them on his father’s side. Perhaps related was too strong a word but his father was from Gujarat too and in some instances that was relation enough. His mother was a countrywoman. Khalifa’s father met her when he was working on the farm of a big Indian landowner, two days’ journey from the town, where he stayed for most of his adult life. Khalifa did not look Indian, or not the kind of Indian they were used to seeing in that part of the world. His complexion, his hair, his nose, all favoured his African mother but he loved to announce his lineage when it suited him. Yes, yes, my father was an Indian. I don’t look it, hey? He married my mother and stayed loyal to her. Some Indian men play around with African women until they are ready to send for an Indian wife then abandon them. My father never left my mother.

His father’s name was Qassim and he was born in a small village in Gujarat which had its rich and its poor, its Hindus and its Muslims and even some Hubshi Christians. Qassim’s family was Muslim and poor. He grew up a diligent boy who was used to hardship. He was sent to a mosque school in his village and then to a Gujarati-speaking government school in the town near his home. His own father was a tax collector who travelled the countryside for his employer, and it was his idea that Qassim should be sent to school so that he too could become a tax collector or something similarly respectable. His father did not live with them. He only ever came to see them two or three times in a year. Qassim’s mother looked after her blind mother-in-law as well as five children. He was the eldest and he had a younger brother and three sisters. Two of his sisters, the two youngest, died when they were small. Their father sent money now and then but they had to look after themselves in the village and do whatever work they could find. When Qassim was old enough, his teachers at the Gujarati-speaking school encouraged him to sit for a scholarship at an elementary English-medium school in Bombay, and after that his luck began to change. His father and other relatives arranged a loan to allow him to lodge as best he could in Bombay while he attended the school. In time his situation improved because he became a lodger with the family of a school friend, who also helped him to find work as a tutor of younger children. The few annas he earned there helped him to support himself.

Soon after he finished school, an offer came for him to join a landowner’s book-keeping team on the coast of Africa. It seemed like a blessing, opening a door to a livelihood for him and perhaps some adventure. The offer came through the imam of his home village. The landowner’s antecedents came from the same village in the distant past, and they always sent for a book-keeper from there when they needed one. It was to ensure someone loyal and dependent was looking after their affairs. Every year during the fasting month Qassim sent to the imam of his home village a sum of money, which the landowner kept aside from his wages, to pass on to his family. He never returned to Gujarat.

That was the story Khalifa’s father told him about his own struggles as a child. He told him because that is what fathers do to their children and because he wanted the boy to want more. He taught him to read and write in the roman alphabet and to understand the basics of arithmetic. Then when Khalifa was a little older, about eleven or so, he sent the boy to a private tutor in the nearby town who taught him mathematics and book-keeping and an elementary English vocabulary. These were ambitions and practices his father had brought with him from India, but which were unfulfilled in his own life.

Khalifa was not the tutor’s only student. There were four of them, all Indian boys. They lodged with their teacher, sleeping on the floor in the downstairs hallway under the stairs where they also had their meals. They were never allowed upstairs. Their classroom was a small room with mats on the floor and a high barred window, too high for them to see out although they could smell the open drain running past the back of the house. Their tutor kept the room locked after lessons and treated it as a sacred space, which they must sweep and dust every morning before lessons began. They had lessons first thing and then again in the late afternoon before it became too dark. In the early afternoon, after his lunch, the tutor always went to sleep, and they did not have lessons in the evening to save on candles. In the hours that were their own they found work in the market or on the shore or else wandered the streets. Khalifa did not suspect with what nostalgia he would remember those days in later life.

~~~

- Abdulrazak Gurnah is the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (2021). He is the author of ten novels: Memory of Departure, Pilgrims Way, Dottie, Paradise (shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Whitbread Award), Admiring Silence, By the Sea (longlisted for the Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Award), Desertion (shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize) The Last Gift, Gravel Heart, and Afterlives, which was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Fiction 2021 and longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize. He was Professor of English at the University of Kent, and was a Man Booker Prize judge in 2016. He lives in Canterbury.

~~~

Publisher information

‘To read Afterlives is to be returned to the joy of storytelling.’—Aminatta Forna

‘Effortlessly compelling storytelling … You forget that you are reading fiction, it feels so real.’—Leila Aboulela

Restless, ambitious Ilyas was stolen from his parents by the Schutzruppe askari, the German colonial troops; after years away, he returns to his village to find his parents gone, and his sister Afiya given away.

Hamza was not stolen, but was sold; he has come of age in the army, at the right hand of an officer whose control has ensured his protection but marked him for life. Hamza does not have words for how the war ended for him. Returning to the town of his childhood, all he wants is work, however humble, and security—and the beautiful Afiya.

The century is young. The Germans and the British and the French and the Belgians and whoever else have drawn their maps and signed their treaties and divided up Africa. As they seek complete dominion they are forced to extinguish revolt after revolt by the colonised. The conflict in Europe opens another arena in east Africa where a brutal war devastates the landscape.

As these interlinked friends and survivors come and go, live and work and fall in love, the shadow of a new war lengthens and darkens, ready to snatch them up and carry them away.