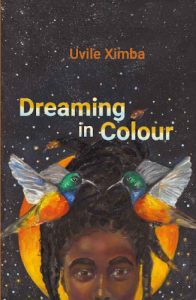

The JRB presents an excerpt from Dreaming in Colour, the debut novel by Uvile Ximba.

Dreaming in Colour

Uvile Ximba

Modjaji Books

Read the excerpt:

1

First dream

‘Tea?’

She was wearing a navy, knee-length skirt that danced around her hips and the yellow, v-neck t-shirt complemented her dark complexion. Thuli, she had said I should call her. That was the first thing that had surprised me. How easy and light-hearted she was. As if the yellow of her top infused itself into her mood. There were smiles all round.

All broad smile and gleaming white teeth, she grinned down at me. ‘Tea, Langa?’

It was one of those thickly hot days when it felt as if the sun was sitting on the living room sofa. The windows were open and a slight breeze brushed the curtains back and forth. I had been airing my armpits slightly every few moments to let a breeze dry up the clamminess there. Steam rose from the spout of the teapot.

‘Yes, I’d love some tea, ma—’ I remembered her request, ‘Thuli.’

A giggle tickled her throat and she smiled at me again. Her living room was a neat, generic space: white sofas, a red carpet and tinges of both colours matched in the cushions and frames on the wall. The glass table was pristine and uncluttered. I noted the dedication to cleanliness.

Thuli’s daughter, uKhwezi, was hidden in the armchair next to mine, curled up and quietly watching us both.

‘So what’s this you want to talk to me about?’ Thuli asked, settling onto the sofa opposite Khwezi and myself. Her question reminded me of the many visits to therapy I’d made. An open-ended yet leading question.

I glanced at uKhwezi. She looked back at me as she shifted forward to the edge of her seat. I could see the question floating in her head, the fantasy of the moment, her tense jaws working against one another. We had rehearsed this conversation together for the past week, anticipating every possible reaction her mother Thuli might have to the question’s answer. Driving to the house earlier, a street away, Khwezi had pulled onto the pavement. The car’s engine had trembled beneath us, mimicking her nervousness.

‘Ask me again.’

Now I glanced at Khwezi. Her eyes looked past mine, into those of her mother. Everything was yellow; the sun washing through the windows, bouncing off surfaces onto our retinas.

Thuli giggled once more, that light infectious laugh: ‘Ask you again?’

Khwezi nodded.

Thuli repeated: ‘What would you like to talk to me about?’

I melted back deep into my chair, nervous, trying to give them space yet watching both of them closely.

***

Awakening.

Khwezi’s eyes blinked and stuttered open. She shut them again against the light filtering through the curtains.

‘Khwezi! Vuka!’ I descended onto her, ripping the blankets off the bed, and levelling my face close to hers.

‘Whaaat?’ she moaned, her eyelids sliding apart. I could see the grey dot-dots in her eyes, like swimming fish in a bowl of milk. With one a bigger brown whale.

‘I had a dream,’ I announced.

‘That’s what most people do when they sleep, no?’

‘Hmmmmm, mmmmm.’ My dreadlocks flew from side to side as I shook my head, ‘Not like this dream, Khwezi.’

I let her climb out of bed and head for the toilet, knowing I could make her turn back any moment. Her long, lean legs sliced across the room as her sleep-dulled feet greeted the ground for the day. She stretched the sleep out of her back, light casting shadows along the grooves in her body. When she reached the bathroom door, I opened up. ‘It was about your mother.’

As expected, she stopped and turned towards me: ‘Uh-huh?’

I nodded towards the empty space on the bed, beckoning her back to me. She defied me and slid into the bathroom. A steady stream of water tinkled loudly, followed by the whisper of toilet paper.

‘Do you want coffee first?’ she called out.

I made really bad coffee, tea, anything hot. Even my grandmother, uGogo Zonto—Lover of Hot Drinks—often refused to drink anything that was the spawn of me and a kettle.

‘Sure. After I tell you.’

Following another stream of running water from the tap, she paraded back to the bed. I could tell by the way she pulled up the blankets that she was irritated I’d woken her up.

‘Okay?’ she mumbled.

Intently, she sat there, listening to me unfold the soft, happy yellow dream of her coming out to her mother. Her eyes swam with the motes drifting through gaps in her mother’s red curtains. They spilled over when I relayed her dream mother’s blessing. Silently, she rose, stood above me and laughed.

uGogo Zonto always used to speak about her dreams. Indirectly to me, but more deliberately to others. Fragments would present themselves while I offered tea and spoonfuls of sugar, and cleared away plates of uneaten food. When her church and stokvel friends came over, I knew to hang around the door because they shared all the juice in whispers. If I didn’t catch the gist of those murmurs and whispers, I would end up fishing out only the skimpy leftovers of the story amidst exclamations of awe and dismay.

‘Jehova!’

‘Hawu!’

‘Unamanga Zonto’.

I knew all the different symbols and metaphors that mattered in dreams. Snakes were trouble and danger, not a good thing to dream about. Fish were carriers of fertility and often associated with pregnancy. Death, ironically, was a good omen. Listening to my grandmother say to her friends, ‘Ngiphuphe uJoyce eshada’, was often the highlight of my day. Although this didn’t bode well for uJoyce, as her marriage spelled out only doom.

For me, sleep has always presaged a fortune-teller. c

Yet uKhwezi stood in front of me, rocking back and forth, her body a vibrating maraca of laughter.

‘Yini ngawe?’ I asked, annoyed.

She paused briefly, looking at me before cackling again, ‘Yellow? My mother hates yellow!’

‘Ngi-serious, Khwezi, mani. It just makes sense. I think it’s time that—’

‘Because you dreamed about it. Really?’

She had stopped laughing and was now glaring at me. An argument was brewing in her lip, making it quiver. I could see her tongue straining against the gaps in her teeth, ready to defend her position. Opting not to answer, I nodded, returning a softer gaze. She shook her dreadlocked head.

‘I’m going to make coffee.’

I watched her saunter to the kitchen before she added defensively, ‘Want some?’

‘Come on Khwezi. I’m trying to explain …’ She shook her head again. ‘Okay, ke. Tea,’ I conceded.

The curtains in our bachelor flat were all slightly parted, welcoming in muted sounds of Makhanda street life outside. Flopping over onto my stomach, I spied on the world through one of the openings. Our space was on New Street, directly opposite Butch’s Liquor Store a few addresses away from student nightlife spots. A pair of birds, a couple, flew onto the window sill, pecking playfully at each other and twittering. We all three looked down at the empty street. It was Sunday. Shops were closed and the town was heavy with a vodka-beer-boxed-wine babalaas.

The smell of coffee and brewed berries crept up from behind me. Two mugs hovered above me as I turned. I took the one Khwezi thrust towards me and moved over so she could join me on the bed. The sound of me sipping berry tea was punctuated by the clink of her teaspoon as she slid it along her mug’s rim, skating on the edge.

‘Not right now,’ she said.

I nodded.

~~~

- Uvile Memory Samkelisiwe Ximba is a theatre-maker, writer and creative practitioner. She completed her BA (Hons) in Politics and International Relations and Dramatic Arts. She is an ASSITEJ South Africa ‘In The Works’ 2020 playwright, and works as an intern at Sonke Gender Justice. Ximba is the co-founder of multimedia production Thamba Creatives, premised on telling women’s stories in South Africa.

~~~

Publisher information

In her debut novel, Dreaming in Colour, Uvile Ximba explores with subtlety, humour and probing insight the connections between the joyful reclaiming of pleasure and the healing of buried traumas.

As students at university in Makhanda during the #RUReferenceList campaign, Langa and her lover Khwezi have a passionate and complex relationship. Puzzling gaps in her memory haunt Langa, yet her dreams are vivid with colours and symbols that hint at a nightmare of forgotten violations and losses. So many secrets—and Langa has had enough of secrets and silences. Who can she turn to? Her mother? Her grandmother? Khwezi? Or herself?

Dreaming In Colour is Langa’s story of coming out to herself, of discerning the history behind the closed door of conscious memory.