Contributing Editor Efemia Chela speaks to Raven Leilani about desire, contradictions, intimacy, and her debut novel Luster.

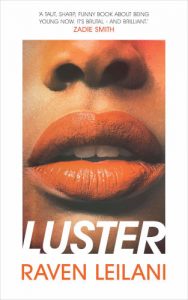

Luster

Raven Leilani

Picador, 2020

Raven Leilani’s debut novel Luster is the story of Edie, a twenty-something who works in the ironically cutthroat world of New York children’s book publishing. She doesn’t paint enough anymore and is trying to outrun student loan repayments, her dysfunctional bowels and the threat of genteel millennial poverty. She starts seeing an older man, Eric, and becomes a curious ‘third’ in the open marriage he has with his wife Rebecca. An unlikely familial bond forms between Edie, Rebecca and their black adopted daughter Akila, a misfit in the anodyne white suburbs of New Jersey. But it is uncertain how long the lustre of it all will last. In a fresh prose style reminiscent of no one but herself, Leilani sketches a darkly humorous portrait of the artist as a young black woman in the 21st century. Luster is an excellent debut, at times suffocatingly intimate and bitterly wise about racial politics, desire and the surprising disconnect between who we want to care for us and who ends up caring for us instead.

Efemia Chela for The JRB: I really loved Luster. I had to read it really slowly because it touched me in still tender places, it felt like the diary of my misspent twenties, although far more coherently rendered. Thank you for writing it. How and when did the idea for this story come to you?

Raven Leilani: Thank you for saying that! I started this book while I was a year into the graduate program at NYU I was working full time and in school full time, and I was trying my damnedest to finish the book. Being in a place where I felt I had the permission to write, having guidance from writers I admired, I felt I had to make the most of the time I had. I threw away the project I came to New York with, and I started this book. I started with the body and with art. I wanted to write a black woman who is unapologetically carnal and who has a complex, human path toward her art.

The JRB: There are some parallels between you and Edie, both painters, both young black women. What was it like working with the (at least demographical) nearness of a character so close to you?

Raven Leilani: More than anything, I wanted to write an intentional and engaging story. I felt I couldn’t take the attention of my audience as a given, so I focused on the craft, on writing toward what felt true and at times uncomfortable. I wanted to write a book where a black woman is allowed the latitude to make mistakes, a book where an artist’s journey accounts for the detours.

The JRB: I like what you say about allowing black women to make mistakes. I think in a culture that either deifies black women as ‘goddesses’ or reduces them to ‘hoes’, we lose a lot of stories that centre nuance.

Could you speak to how your visual art practice informs, and perhaps reforms, your creative writing practice?

Raven Leilani: I think both require a respect for the data, or a commitment to looking closely. Both are about discovery. Being a student of both painting and writing opened my mind to the necessity of curiosity and close observation, and it made me less dogmatic about how we go about reflecting our reality. You can have all the cathedrals. You can have the hyperrealist and the shaggy and impressionist.

The JRB: In her poignant essay ‘What Fullness Is: On Getting Weight Reduction Surgery’, Roxane Gay describes her own desire: ‘I hate the way I hunger but never find satisfaction. I want and want and want but never allow myself to reach for what I truly want, leaving that want raging desperately beneath the surface of my skin.’ As the principle ‘lust-er’ of the novel, what do you think Edie gets right and wrong about desire?

Raven Leilani: For me, it wasn’t about right and wrong. I was writing against what might have been a neater, more moralistic approach to this story. I think it is telling that a lot of art that centres women and their desire is subject to moral questions, or what lessons are learned, rather than a reckoning with a context that makes the visibility of this desire rare enough to be radical, or a reckoning with the narrowness of looking for binaries in a thing that is inherently messy. To be human is to be able to hold contradictions alongside each other, and Edie does, though of course she is wrong as much as she is right, maybe even more than that. But finding your way to what you want often involves trial and error.

The JRB: The trial and error certainly makes us beautifully human. You have such a refreshing aphoristic metaphorical style: ‘the ecstatic rutting and cushy ether of the void’; ‘the liquid centres of my teeth’; ‘any uppercase emotion’; ‘my window will constrict into the shape of a lung’. How do you go about crafting these tiny poems in your storytelling?

Raven Leilani: Thank you! Before painting, I really loved poetry, its intentionality and economy. I love when you can feel the joy on the sentence level, the energy and respect for the granular, sensory details. I wish there were a better way to describe how the language comes together for me, but I feel like I’m often writing in a total fugue state, after I’ve figured out the shape and bones. I think I’m just obsessed with trying to articulate the feeling of a thing as precisely as I can, in a way that feels good and hopefully surprising.

The JRB: I noticed that the Rebecca–Eric–Edie dynamic sort of reflects the historical sexual dynamics of a Southern United States slave plantation—white plantation owner, white wife of plantation owner, black mistress, a slave in constrained circumstances sleeping, or coerced into sleeping with the plantation owner. Of course Edie isn’t a slave, she’s free-ish, but the racial legacies of slavery impact her.

Raven Leilani: Edie is a black woman moving through the world. Her race and gender have enormous bearing on how she interacts with her environment and how it interacts with her. If I was going to honestly depict the life of a black woman, what it looks like when she tries to seize the right to make art, what it looks like when she tries to seek pleasure—all of the answers to these questions are informed by her environment, which is sexist, racist, and capitalist.

The JRB: There’s a lot of sex in Luster but also a wealth of non-sexual intimacy, Edie mixing paint with her fingers, Edie carefully oiling Akila’s scalp, Edie rendering her not-so-nemesis Rebecca on the canvas. What are some of your favourite examples of intimacy in literature or other works of art?

Raven Leilani: Bryan Washington’s short story ‘Heirloom’ is so good and full of the slow, tenuous intimacy of two strangers drawing near to each other through the preparation of food. I also love Edward Hopper’s ‘Room In New York’. It may be sacrilege to say that this painting is an example of non-sexual intimacy, considering the deep thread of loneliness throughout his work, which is present even in this piece, where two figures sit in the same room involved in separate activities, nearly invisible to each other, but that to me is a kind of intimacy—being able to be alone with yourself, with another person.

The JRB: That’s an interesting way of looking at Hopper, as an interplay of solitude and intimacy. One of my favourites is ‘Morning Sun’, where—I think he used his wife for the sketches—even though she is all alone, the quality of the light pouring through the window makes it feel like she’s being held by something grand and invisible.

Will you be continuing in what Edie calls ‘the fiscal wasteland of the arts’? [Laughs] And if so what can we look forward to from you next? An art exhibition hosted in your Animal Crossing, perhaps?

Raven Leilani: I will be continuing! I love writing and hope I get to do it as long as I’m living. I have a few more novels in me, so hopefully soon there will be more books, though an exhibit in Animal Crossing does sound more preferable at the moment.

- Efemia Chela is Contributing Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

I would like to send a copy of this book to my sister in England. Where can I find the book , or better still find someone who can send the book directly! Annemarie