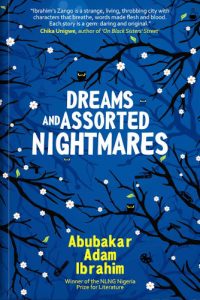

The JRB presents an excerpt from the title story of Dreams and Assorted Nightmares, the new collection by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim.

Dreams and Assorted Nightmares

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim

Masobe Books, 2020

Read the excerpt:

Dreams and Assorted Nightmares

No one knew what to call the place that was halfway between dreams—a patch of earth, hugged on one side by a murky river and hedged on the other by a series of mournful hills and a dark forest, a place where travellers rested before moving on—so they just called it Zango. The layover. At least, that was what Laminde’s grandmother, Kaka, had told her when they were shelling groundnuts for soup. Kaka’s earnest face like crumpled, dusty khaki was set in a perpetual brood and her biddy eyes stared down at little Laminde, as if to burn off any doubts the child might have regarding this account. But Laminde’s seven-year-old mind believed that Kaka was as old as the world itself and had been sitting on a tree bough snacking on gurjiya, watching God’s magic split heaven and earth.

‘For years, it was just a sleepy in-between place until some itinerants got drunk on rest and forgot to complete their journeys. Their wives and children, and in some cases their husbands too, tired of waiting for them to return, packed their belongings in ashasha sacks and joined them,’ Kaka had said, eyes staring past Laminde, as if saying this tasked her memory, as if the child had disappeared into a haze, unnoticed, uncelebrated, just the way Zango had been birthed. It was years later that Laminde would fill in the blanks that Kaka’s long silences were with things she gathered from conversations in markets, at school, and the other places secret histories were procured from.

After the wives came, prostitutes who serviced the travelling men set up permanent shacks not far from the park where the roar of truck engines and the blare of car horns masked the noises of indiscretion, and Zango became home for good. This bit, her grandmother never said, but Laminde knew. Everyone did. The prostitutes’ shacks still stood and, in their rafters, if one looked carefully, traces of the dust stirred by the first men who had made Zango a town, and their trucks, could be found.

Zango was a river. In parts slow and sluggish, a contented serpent resting from the kill, and in others turbulent and restless. In full flow, Zango, like most ungovernable rivers, collected moss and mud, and little animals that sometimes slipped from its banks. On occasions, it collected the big ones too, those who thought they were too immense for the tides. This, Laminde, by observing, had learnt for herself.

Zango had emptied before, leaving only a deep scar in the earth. And like a river, it had reinvented itself.

‘Before this place was called Zango, it was once called Mazade by a people consumed by a plague,’ Kaka had said, staring before her as if she could see the deserted houses in the evening sun being eaten by termites. But Kaka was already losing her mind at the time and no one knew for sure if she remembered anything right.

What Laminde did know years later, sitting by her window and looking out into the streets filled with residents and travellers, was that deaths in Zango were often as dramatic as life in her was. Sometimes they were bizarre, such as the time Babale died on the eve of his wedding, gored by a rampaging bull that had escaped its minders. The bull, fleeing after its gory deed, fell into a gaping manhole and snapped its neck. Or when the matriarch Balaraba, long afflicted with gloom, was found dead in her cane chair, facing the door with a smile on her face. Nobody knew what she had been waiting for, or what had come through the door and left with her soul. But her smile endured, its impression visible through her shroud even when they laid her in the grave.

Babangida too died happy. He had lived most of his life trawling the streets of Zango, feeding off people’s throwaways. One afternoon, he stood, pole stiff, in the middle of the street and started laughing. He laughed nonstop for three hours and forty-seven minutes before he slumped.

‘Allah sarki! His leaf has fallen,’ a bread hawker said, as a crowd ringed the fallen figure, debating the merit of touching a dead or dying mad man with grime on the back of his neck.

‘Poor bastard laughed his life out,’ one of the pallbearers said as they carried him to the cemetery.

Once or twice a year, a corpse with an erect manhood would be found by the riverside. If the rumours were to be believed, they had died in the brothels, from manpower overdose. The whores and their pimps would carry them out and dump them in the river so they could wash up elsewhere. Sometimes they just left them on the banks. Because these men were mostly strangers on failed conquests of the whorehouses of Zango, not much was made of their deaths, or unceremonious disposals, beyond the spectacle and inconvenience they caused.

In Laminde’s estimation, none of the dramatic deaths had yet eclipsed Vera’s. Vera had been sitting at her usual place under the pedestrian bridge braiding a customer’s hair, as she had been doing for years, when she started coughing out strands of hair. When the first hairballs came out, the crowd of horrified women that had gathered, drawn by her violent fits, oohed. They watched her heave and pull out a long strip of braided hair that went on and on and on until it seemed she had swallowed a pony-tailed woman. After the braid slipped out, all one meter, seven centimetres of it—because Zaki, son of Kore the bandit, actually measured it—coiled in front of her like a juvenile python, Vera keeled over. Her face, half-buried in the mass of hair and puke, conveyed the full horror of what she had seen come out of her.

It was this kind of death, this particular one with its attendant horror and agony, that Laminde wished for her co-wife Ramatu.

- Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is a Nigerian creative writer and journalist. His debut short story collection The Whispering Trees was longlisted for the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature in 2014, with the title story shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing. His first novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, won the Nigerian Prize for Literature, Africa’s largest literary prize, in 2016. He is the Features Editor at the Daily Trust newspaper. In May 2018 he was announced as the winner of the Michael Elliot Award for Excellence in African Storytelling for his report ‘All That Was Familiar’, published in Granta magazine. Dreams and Assorted Nightmares is his third book and second collection of short stories.

~~~

Publisher information

Zango is a surreal town where men, some with erect manhoods, die when leaves fall from a life tree.

Zango is both setting and spectre for Dreams and Assorted Nightmares, a collection of interconnecting short stories which explore the spaces between life and death and beyond.

There’s a poignant story of a special needs boy with prescience; another about the family of a philandering artist trying to pick up the pieces after his violent death; one of a teen forced to make a heart-breaking choice after her mother disappears; and another about a woman who reveals a terrible secret to her childhood friend who is in a coma. The characters come richly-layered and memorable—like Naznine who had but slowly lost the most perfect smile in the world; new bride, Nana Aisha, left alone to face armed marauders who invade her home; and brigands, Audu Kore and Maimuna Dajjaj, who share a pure and precious love.

The stories mostly feel mystical and dark, but the palpable compassion with which they are written give them warmth and light. Like rivulets, the stories easily flow into each other, aided by Ibrahim’s signature hypnotic writing and majestic prose. This is a collection to savour especially for its many enigmas—the silent poetry and tragedies of everyday life, the darkness and tenderness of the human mind, and the crossroads between dreams and the supernatural.