George Bizos, esteemed human rights lawyer who fought tirelessly against the apartheid system, has died.

Bizos was born on 15 November 1927 in Vasilitsi, Greece, and died on 9 September 2020 in Johannesburg, South Africa. He was ninety-two.

President Cyril Ramaphosa announced his death, saying Bizos had ‘contributed immensely to our democracy’, adding:

‘He had an incisive legal mind and was one of the architects of our Constitution. We will forever remember his contribution. […]

‘We have lost a monumental figure in our history; a patriot who marched with us to freedom and laid the foundations for a democratic South Africa in which the rule of law affirms the dignity, rights and protection of all who live in South Africa.’

His family said he ‘died peacefully at home of natural causes’.

‘Mr Bizos belonged to the outstanding, courageous, and special generation of leadership that strived and dedicated their entire life to the restoration of the dignity of all people. He was, without doubt, one of the greatest giants of our liberation struggle who not only ushered in a new dispensation but also played an instrumental role in setting up crucial systems to anchor our democracy.’—Statement by Parliament’s Presiding Officers

Bizos fled the Nazi occupation of his native Greece with his father in 1941, when he was thirteen, and arrived in South Africa as a refugee, speaking neither English or Afrikaans and missing a couple of years of school as a result. The rest of his family, including his mother, came to South Africa only in the nineteen-fifties.

Bizos was very fond of his adopted city of Johannesburg, and as a child used to enjoy rowing boats at Zoo Lake and Germiston Lake. He said in an interview, wryly:

‘I have always been optimistic about the future of the city and the country, despite the difficulties … I have a sense of enjoyment at the mine dumps.’

While studying for a BA and then a law degree at Wits University, Bizos became politically active, joining the Students’ Representative Council under the leadership of anti-apartheid activist Harold Wolpe.

Bizos joined the Bar in Johannesburg in 1954, and during the nineteen-fifties and sixties defended a number of anti-apartheid figures, including Trevor Huddleston, Sophiatown’s much loved priest and activist.

But Bizos will be remember most strongly for representing Nelson Mandela during the 1963–64 Rivonia Trial. Bizos was part of the team, led by Bram Fischer, that defended Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu. He suggest Mandela add the qualification ‘if needs be’ to the statement that concluded his trial address:

‘I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.’

—which Bizos believed was the difference between a life sentence and the death penalty for the defendants.

Bizos also acted as counsel at various high profile apartheid-era trials, such as that of Bram Fischer, and inquests into the deaths of people in detention, including Steve Biko, Ahmed Timol and Neil Aggett. He represented the families of anti-apartheid activists killed by the government throughout the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and was the leader of the team that opposed applications for amnesty at the TRC on behalf of the Biko, Hani, Slovo and Schoon families, and the families of the Cradock Four, Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli.

In 1985, Bizos led the defence in the Delmas Treason Trial, the prosecution of twenty-two anti-apartheid activists including three senior leaders of the United Democratic Front, Moses Chikane, Mosiuoa Lekota and Popo Molefe. The same year, he was appointed judge on the Botswana Court of Appeal, where he served until 1993.

In 1990, Bizos became a member of the ANC’s Legal and Constitutional Committee, playing a key role in the drafting of the Bill of Rights, and served as an advisor to the negotiating teams at the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), participating in drawing up the Interim Constitution. He also represented the government before the Constitutional Court for the abolition of the death penalty. In 1994, then-President Mandela appointed Bizos to the Judicial Services Commission.

As senior counsel of the Legal Resources Centre, Bizos was among the lawyers who represented some of the families of the miners killed by police at Marikana in 2012.

Bizos defended Winnie Madikizela-Mandela on multiple occasions, including during the controversial Stompie Seipei murder trial, and in 2004 Bizos defended Morgan Tsvangirai, president of the Movement for Democratic Change, Zimbabwe’s main opposition party, against a charged of high treason by Zimbabwean government. Tsvangirai was acquitted.

Outside of the law, in the nineteen-seventies Bizos helped found SAHETI, an independent, racially integrated Greek school based in Johannesburg, and he was known as a keen vegetable gardener.

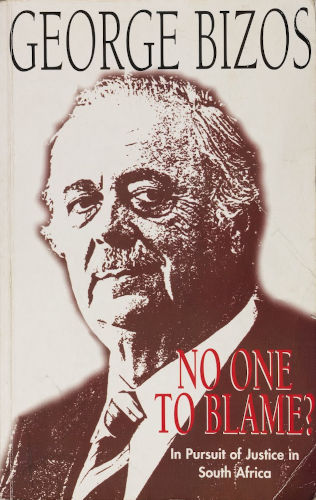

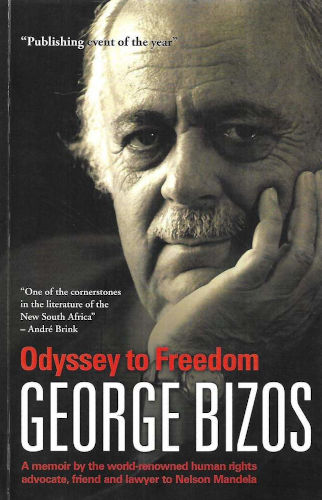

Bizos wrote a number of books in his lifetime, including No One to Blame?: In Pursuit of Justice in South Africa (1998), in which he gives a personal account of the steady erosion of justice in South Africa during the apartheid years, and his disappointment with aspects of the TRC; Odyssey to Freedom (2007), his extraordinary biography; and 65 Years of Friendship, which documents his long friendship with Mandela, who he met when they were both students at Wits in the nineteen-forties.

‘I have lived through the joys and sorrows of the South African people. That’s what really binds you to a country. I’ve done that. I was able to make a small contribution towards liberty coming to the people of South Africa.’—George Bizos, 21 Icons

Bizos received many awards for his work over the years. In 1999, then-president Mandela awarded him the Order for Meritorious Service Class 2, and in 2001 he received the International Trial Lawyer Prize of the Year from the International Academy of Trial Lawyers. In 2004, he received the International Bar Association’s prestigious Bernard Simons Memorial Award for the Advancement of Human Rights ‘for his outstanding contribution to human rights law in South Africa’. Mandela was one of the many who nominated Bizos for the award, saying: ‘I know of no person more worthy for this honour’. That same year, Bizos received the Sydney and Felicia Kentridge Award for Service to Law in Southern Africa, from the General Council of the Bar.

Bizos’s wife, Arethe Daflos, an artist, died in 2017. He is survived by three sons and seven grandchildren. The JRB extends condolences to his friends and family.