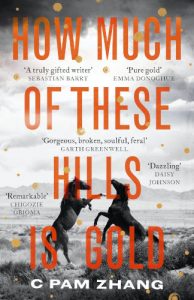

The JRB presents an excerpt from How Much of These Hills is Gold by C Pam Zhang, a revisionist immigrant fable set during the American gold rush.

How Much of These Hills is Gold

C Pam Zhang

Little, Brown, 2020

About the book

Set during the Gold Rush, in a reimagined American West, Lucy and Sam, twelve and eleven, are newly orphaned siblings.

With their father’s body on their backs, they roam an unforgiving landscape dotted with buffalo bones and tiger paw prints, searching for a place to give him a proper burial. The siblings must battle with their own memories, the illusion of the American Dream and each other.

How Much of These Hills is Gold is an epic debut novel about family and the search for both a home and a fortune.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Lucy chooses where they won’t bump into Anna. A grease-spotted place by the station, where Sam orders without consulting the menu. Two steaks, a sour cook, and Sam aiming a smile so wide the woman walks away stunned, her own mouth turned up seemingly against her will. Meanwhile Lucy’s appetite slunk out the door at the sight of the flypaper. She asks for water. Sam watches her wipe her dirty fork, then calls across the restaurant.

‘Miss?’ Diners turn. ‘Miss, you with the beautiful curls.’ The cook, greying hair in a twist, looks up from onions in astonishment. ‘We’d appreciate fresh cutlery. If you’ve got it. Thanks greatly, miss.’

‘Don’t make a fuss,’ Lucy hisses, adjusting her hair over her face.

‘They’ll look no matter what.’

Sam, as usual, makes that true. Drapes over the rickety chair as if it’s a lounge in Anna’s parlor. If Lucy learned to go unseen, then Sam spent five years polishing a natural shine brighter. Sam’s walk is bolder, Sam’s shoulders straighter. A new bandana at the throat hides Sam’s lack of Adam’s apple. Look hard and Lucy can see remnants of the pretty girl-child: long lashes, smooth skin. But it’s like trying to fix on an animal moving through the grass at the jackal hour. Your eyes make you question.

What most people see is a man. Handsome as Ba must have been before life cut its marks in him. All Ma’s charm and grace. Likely that’s why the two steaks come so quick, why the cook flashes another gummy smile.

Sam falls upon the food with an old ferocity. Lucy spins her water glass, remembering starvation. Damp on her fingers, a matching damp in her eyes. What Sam stirs up is unwelcome. Murky.

Sam mistakes Lucy’s gaze. ‘Do you want the second steak?’

‘I can’t. I’ll ruin my dress.’ Lucy brushes the white fabric, imported special by Anna’s father. She doesn’t want to explain its cost, or Anna, or Anna’s father. To distract she says, ‘Tell me where you’ve been.’

Sam takes another bite, leans back. At sixteen, Sam’s voice is unaccountably deep, with a singsong rhythm. Easy in this heat to imagine Sam spinning these tales by a campfire. They have the cadence of practice, like Lucy’s orphan story. These—Lucy’s eyes prick—are stories Sam shares with strangers.

Sam fell in with cowboys to lead a great cattle drive North. Traveled with adventurers to a lost Indian city in the South. Trekked up a mountain with a sole companion to see the world laid out from the peak. Sam chews and talks, swallows and boasts, and hunger roams in Lucy. A hunger for wild places, for paths that twist so you can’t see their ends, for fear of the kind missing along with wildness in Sweetwater. A hunger for the trail that makes unsalted oats and cold beans into a feast, the trail that sears the body awake, not this sluggish place, this orderly place where all the streets are mapped and known.

‘Where will you go now?’ Lucy asks when Sam stops. The restaurant’s gone quiet, yet an echo remains—a kind of ringing inside Lucy, as when one glass strikes another and sets it in motion too. She almost doesn’t recognize it for hope. ‘With who?’

Sam scrapes a fork over the empty plate. ‘I’m going alone this time. Had enough of traveling in packs. I’m planning to go pretty far, and I figure I won’t come back. So I figured—I figured I’d say goodbye.’

The hunger in Lucy is grown so vast, she fears she might collapse into it. She calls for her own steak. Intends just to nibble. But the meat occupies her mouth and eyes so she doesn’t have to speak or look at Sam, doesn’t have to fear the keenness of her disappointment showing through. She lifts her plate to hide her face, and laps the bloody juices.

Sam pushes the other two plates across. Lucy licks those clean too. Only then does she look down at her dress. It’s ruined, spattered with small pink drops.

Sam says, ‘It suits you.’

Anger clarifies. This is Sam mocking again, come through town to upturn everything—selfish through and through. She reaches for the bill when it arrives, intending to call this a goodbye gift.

But Sam’s quicker. Like some magic trick, Sam’s brown hand slaps down—and when it lifts, there remains a flake of pure gold.

Lucy throws both hands, a forearm, over the sight. ‘Have you been prospecting?’ Fear hums through her. She looks around, but none of the other diners have moved. The rest of the room seems suspended in torpor. ‘You know you can’t. The law—’

‘I didn’t prospect for it. I was paid by some gold men I worked for.’

‘Why in the world would you do that?’

‘Didn’t you ever wonder?’ The swagger leaves Sam’s voice. For the first time Sam speaks softly, conscious of the other diners. ‘We weren’t the only ones wronged. There’s others, Indian and brown and black. None of us think it was right, what got took from us. Didn’t you wonder what the gold men did with what honest folks dug up?’

Up this close, Lucy sees what she missed under Sam’s charm. Beneath is the same mix of violence and bitterness and hope that killed Ba. That old history that Lucy orphaned herself from.

‘Those gold men really think this land belongs to them,’ Sam says, scornful. ‘Isn’t that the greatest joke?’

Lucy can’t locate her laughter. What she can locate is the precise spot on a wall, in the biggest house in town, where a deed hangs in a frame that, if melted down and sold, could feed a hundred families. Sam may scorn it, but there it is in a place Sam could never imagine. Lucy pretends to dab at her dress. She knows the answer to Sam’s question, and it shames her. She’s seen where the gold goes. She is a guest in its house, she wears its gifts, she is its friend and walks arm in arm with it through Sweetwater.

~~~

- Born in Beijing, China but mostly an artefact of the United States, C Pam Zhang has lived in thirteen cities and is still looking for home. She’s been awarded fellowships and scholarships from organisations including Bread Loaf, Tin House, Aspen Words and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her work appears in Kenyon Review, McSweeney’s Quarterly, Tin House and elsewhere. She currently lives in San Francisco in the United States.