In February 2020, poet and academic Stella Nyanzi was acquitted and released from prison after being held for eighteen months for insulting Uganda’s president with a poem she posted on Facebook. She wrote a collection of poems during this time.

I was able to finish putting together the manuscript for that collection, No Roses from My Mouth, during my January residency with the Center for Arts, Design + Social Research (CAD/SR). Having this conversation about the book on the CAD/SR Instagram was a full circle moment. It was also the first time Stella Nyanzi had used her Instagram account, and she observed wryly that she had not thought it could be that useful, beyond the occasional selfie.

Before the conversation begins, Stella shows off a few titles by contemporary Ugandan poets that she has been reading during the lockdown: Reveries of Longing by Melissa Kiguwa, The Mammon Tree by Joseph Jabo, Kalimba by Petero Kalulé, Fire on the Mountain: Creative Work on the Obuhirika, edited by Danson Kahyana, Ogenda wa? by Ssebo Lule, Shards of Brokenness by Regina Asinde, Spit my Heart by Zenah Nakanwagi and Hakuna Mchezo, The Dictator Awakened by Obed.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length, but you can watch the full unedited version here.

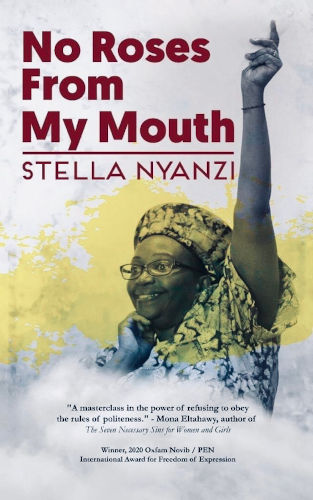

No Roses from My Mouth

Stella Nyanzi, with an introduction by Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire and Esther Mirembe

Ubuntu Reading Group, 2020

Esther Mirembe: How have you been?

Stella Nyanzi: Oh, what shall I say, Esther! I’ve been fine, apprehensive, uncertain, scared, excited, bored. How have you been?

Esther Mirembe: I’ve been alive. That’s how I can summarise it. I’ve been alive.

Stella Nyanzi: Good alive, bad alive?

Esther Mirembe: All things considered, good.

Stella Nyanzi: Are you productive in the lockdown time?

Esther Mirembe: It depends on how you define productive, but I’ve been reading a lot so, yeah, that’s productive.

Stella Nyanzi: Reading is good for writers.

Esther Mirembe: Yeah, it is. And you’ve been reading a lot of poetry yourself.

Stella Nyanzi: Well, sometimes it is the easiest place to go to. Reading poetry is a lot easier than reading dense prose, I think. I’ve also been reading other stuff. Mills and Boons. You know, trash literature that good writers pretend they don’t read.

Esther Mirembe: What does poetry mean to you? And what has it meant to you in this time?

Stella Nyanzi: This time particularly?

Esther Mirembe: Yeah, I think we can start from there.

Stella Nyanzi: I think in the time of Covid-19, I’ve become quite an angry person. As a Ugandan living on the fringes, in the margins of the city, living besides or beneath the corridors of power, where I interact with very many powerful people but I’m not one of them, it’s very easy to get angry at abuse of power, abuse of resources, misuse of an opportunity to work for Ugandan lives. And the anger that’s killing and consuming me tends to get written in short angry outbursts of poetry whose lines are not necessarily neat.

So poetry as a place of release, as a place that I go to to remove some of the insanity threatening to choke me. It’s become a lot in my life, in moments of dire despair or gloom or failure, even. I find that writing poetry, much more than reading or reciting it, is a salvation. Reading poetry many times I think for me is where I go to grow, as an innocent, naive human being who believes in the goodness of all humans. Sometimes I go to poetry to learn that actually we are evil dark monsters. You know?

Esther Mirembe: Mhm.

Stella Nyanzi: I also go there to find others, I go to find kindred spirits in poems, and sometimes I go to get lost. When Uganda becomes a dungeon, a prison, a cold frozen place, it’s good to disappear into the world of some of the funkier poets living in the funkier centuries. And faraway places. Poetry means many things, as an outlet but also as a place from which I receive. A place I pour into and a place I take away from. It’s a mouthpiece, you know? Or you don’t?

Esther Mirembe: I do, because you also wrote a lot of poetry when you were in prison.

Stella Nyanzi: Yeah.

Esther Mirembe: And it seems that the same things it means to you now are the things it meant to you also in prison.

Stella Nyanzi: In prison, I think poetry first and foremost for me was written in resistance, always in resistance. When they took away my books and they refused me access to newspapers, they refused me access to television, for example, I would go to write what I would read for myself.

I also had visitors coming to bring me some of their written poems, coming to recite their poems. There’s a wonderful lady, Daphne Arinda, she came to visit, and she recited these poems that were just taking me out of the prison and into high places. That was very empowering, like smashing the voice of those who said Stella you’re condemned, you’re guilty, you’re very bad. I mean it just changed how I was experiencing prison life.

But I think when I got an opportunity to be published, an opportunity to begin testing the security system in prison, and we had to sneak poems out, hiding them in the bras of women, hiding them in the shoes of men, hiding them between bread sandwiches, tacking them inside court documents, that was an amazing moment of resisting. The idea that a prisoner who was highly surveiled was able to work with others to sneak out poetry, and also to bring it in, was very victorious.

Many of the times I was punished, the prison authority, wardresses or even cooks sometimes, just came and raided my small set of belongings and took out my poems, my notes. That was one of the worst punishments. One of the worst moments of defeat in prison was when human beings abused their uniform to steal, confiscate, tear, sometimes burn, my handwritten poems. It was very defeating, and I was often bitter. But I kept writing and willing myself … that the poems got out whether they got published or not, whether they got shared or not, as an act of resistance.

But also, in prison I was being punished for freedom of expression, because of a poem I wrote, a sweet birthday poem I wrote to the president of Uganda discussing his systematic, systemic oppression of Ugandans. For me, the poem was really toned down. In the moment of writing it I was furious. If I hadn’t used the genitalia of this woman called Esiteri [the president’s mother] in that poem, I would have been very vulgar, but I used female genitalia and the birthing process to comment on what I felt was a dying democracy. All semblances of democracy were dead and dying in Uganda when I was writing the poem. And so, I landed in jail, in the courts, I became a convict, I became an ex-convict, I became an appellant and eventually an acquitted Ugandan. I became an ex-prisoner today because of a poem, one small, beautiful, honest poem. Was it about the poem or was it about repression? And so the power of poetry to expose how repressive the Ugandan dictatorship is … I can never not talk about it when I get an opportunity to talk about poetry. That by arresting and trying and detaining and imprisoning and convicting and sentencing and then acquitting me, the Ugandan state exposed itself for how repressive it was simply because I wrote a poem.

We are supposed to talk about poetry but somehow when I talk about the arts and the ability to express myself using the arts, I end up going political because often I am using the arts to express my politics.

Esther Mirembe: Which is okay because your poetry is very political. In hindsight, how are you relating to the poetry that you wrote in prison?

Stella Nyanzi: How am I relating to it?

Esther Mirembe: Or what do you think of it now?

Stella Nyanzi: I love it. I hate it. I celebrate it. I have been called a poet finally after forty-five years of writing so many poems and being ignored and trashed, and dissed and dismissed, and written off and undermined. Finally, with the book, No Roses from My Mouth, I think that particularly Ugandan writers begin to say, actually she’s a poet. She’s a poet. Suddenly scholars of literature in Uganda who were dismissing my work say, maybe she’s a poet after all. And so that in itself is a redeeming of Stella Nyanzi as the poet, and that should be celebrated.

My children have read my poems and they laugh about some of them, they are horrified about many others. The most honest response I have received has come from my three children at home. One of them was reading the poems and said, ‘Mama are you a lesbian?’ And I said ‘Son, why are you saying that?’ And he says, but you’re writing this poem as if it’s you who is kissing the mouth of this woman, that’s orgasming from this woman. And I’m like, but son, how old are you, I’m your mum. And he’s like, ‘But mum, I’m your audience, I’m not speaking as your son. I’m asking you an honest question as your audience.’

I sometimes feel there’s a lot of pressure arising from the book to only focus on writing for prisoners and writing about the abuses in prison. One of the accolades I received was about finally having the perspective of a woman political prisoner, writing about prison and prisoners, and how we go through this life. And for the first time I realised, hey, there are not very many of us who have done this sort of writing inside the walls of prison.

In a way, I wish I had written a diary. I think it would perhaps have been a better representation of my experiences in prison. But when I was in prison my diaries were just confiscated. They’d take them and sometimes I wondered, what do they do with all the confiscated material they get? Writing poems became easier for me, because if one poem was lost, three others were saved, and one poem in and of itself is good enough. A diary needs to be a daily record. A memoir or a book, a novel, based on my experience would have been harder to write because the plot is much longer. A poem, five lines, three stanzas, done.

I was shocked that the prints ran out within the first month. I was anticipating that it would be banned before we even got it out. I thought the regime would come and hit us hard. Because how can you write about the government in prison? How can one do a critique using written word when one is in jail for their written word? I was pleasantly surprised that rather getting banned, people were asking for copies. The popularity of the book for me was kind of a shock. I didn’t think that Ugandans would want to read poetry from me, let alone read poetry from prison.

We won. The book won an award, I think, or the award came at the same time as the book, the Oxfam Novib/PEN International Award for Freedom of Expression for 2020. While I celebrate the award, I’m also very saddened because it tells a very specific story about freedom to write in Uganda. The fact a writer is in jail, a Facebook writer not even a serious writer. But they’re taking the Facebook writers more seriously than they’re taking ‘real’ writers. Although one must hasten to add that writers such as Rukira Bashaija Kakwenza, who was arrested during the Covid lockdown, writers are being silenced for their writing. I wasn’t the only one, it is actually on the increase. I’ve said so much. What was your question, Esther?

Esther Mirembe: I asked what the poetry meant to you in hindsight. The poetry that you wrote in prison.

Stella Nyanzi: It’s a celebration of many things, some of which are not good, because to celebrate the repressive regime in Uganda is to celebrate something evil. In many ways, the poetry, the book for me represents both dark and light, both good and bad, and it’s more than just me. One has to thank the publishers who were not scared to stand with this imprisoned writer in prison because she’s allegedly offended the president. There can be reprisals for doing that. For standing with a dissident. And so, you know, I want to talk a little bit about the Ubuntu Reading Group, that they too are celebrated, because the book would never have been if there were no publishers.

But the story of how those publishers got the content they published is a story that one must always seek to look for. Poems in the strings of bras of women and in the soles of dirty socks of men with sweaty feet, how do they get these poems into a beautiful book? For me, it shows that the resistance is not just mine alone, it’s not just the writer who should be celebrated. It’s much more. It’s about a group of writers and publishers and the literary world who insist on buying the book and reading it and having readings. That community of writers who know the power of resistance writing (I’m not sure there is a term like that) are also celebrated in the book.

But also, people say who that Ugandans don’t read, Ugandans don’t write, Ugandans don’t rhyme, the book says, fuck you, actually we do. Whoops, am I allowed to say ‘fuck you’ on Instagram?

Esther Mirembe: Yeah, yeah, you are.

Stella Nyanzi: What was I fucking saying just there?

Esther Mirembe: People who say that Ugandans don’t read.

Stella Nyanzi: Exactly because look, I’m a Ugandan, I read and write. I’m not representative of all Ugandans but I read and write, the publishers read and write. The prisoners were reading along with me.

Esther Mirembe: Someone has asked, how did you find the courage to keep writing and speaking out with so much at stake?

Stella Nyanzi: There was no option. If I did not write, I would run mad. It wasn’t being courageous, it was being sane, it was being selfish. It was saying if I don’t let this anger out, I will burst, I will explode. Many times people think, oh my, Stella you’re so strong. No, I wasn’t being strong. I was protecting my own sanity, because there’s only so much a person can take. I think that every time I was writing, I was releasing, just releasing, releasing anger, releasing curiosity. Releasing wonder, like, that just didn’t happen.

Some of the poems I wrote about faith in prison would get me into so much trouble with my highly religious family. But religion is used, wickedly used to domesticate women and cut off their tongues and cut off their bad behavior and keep them in control. I grew to hate religion in prison because women are taught to just obey and say yes and be nice and humble and subservient which is, I think, a wrong interpretation of what religious gods and goddesses, godlings, are calling us to do.

So it wasn’t about being courageous or bold when I was writing in prison, it was really about allowing myself to continue wondering and criticising and critiquing and asking, questioning, but also just appreciating. It doesn’t take courage to appreciate. I don’t think it was courageous. I think it was stubborn, I think it was obstinacy, it was rebellion, it was resistance, it was fighting, it was refusing to do nothing. And it didn’t take me courage to do that. I just had to do it. Do you need courage to breathe? No, you just breathe. I was just breathing.

Esther Mirembe: Someone is asking, what do you think of vulgarity as a tool of resistance?

Stella Nyanzi: I don’t think of it, I use it.

Esther Mirembe: Let me read the exact question. What would you wish people understood about vulgarity as a language and a tool of resistance?

Stella Nyanzi: Right, so one, I think that vulgar, that word, in and of itself is a descriptive term that is highly subjective. For something to be vulgar one looks at it and judges it. There isn’t one standard of judgement. For example, the expression ‘komanyoko’ in Luganda, very dirty word that means ‘fuck your mother’. Like motherfucker in English can be very vulgar or it can be praise, depending on how one delivers it. Right? So if I had a book title that just went komanyoko, what is it saying? Is it vulgar? It’s my book title and it’s komanyoko.

What I want to say is that it is subjective, interpretations of the word. It’s value laden depending on different contexts, a vagina in a lab, in a biology class, in a clinic, at the gynecologist’s, it’s just vagina. Vagina in the president of Uganda’s mouth, what is it? Vagina said by Stella Nyanzi is not the same thing. See what I mean?

I used to get very angry when people used to say, oh she’s vulgar, she’s obscene. I think they’re in one moment telling me about who they are, the prudery within them, and secondly they are also showing me that rather than focus on the issues that have been packaged with vulgarity, they’re just focusing on the vulgarity, as if when I give one a sweet wrapped in blue paper, they consume the wrapper and forget to eat the sweet.

Vulgarity is a tool that I deploy quite consciously. I’m not drunk or mad like they say. I’m not insane when I’m being vulgar; I have seen the power of what they call vulgarity. First and foremost, it grabs an audience like, Ha! She didn’t say that? Yes, she did! The spectacle is created around Nyanzi who talked about the president’s mother’s genitals, but so what? What did she say about those genitals? So to grab an audience, say something graphic and they will come for it, they fall for it. People criticise the tool of vulgarity and yet even they are a part of the audience and so just confirmed that actually it works very well. Vulgarity is not an end in itself, it’s a means to achieving something, it’s a means to communicating much more. If all I did was to say ‘pair of buttocks’, there’s no point to it, but when I say ‘Museveni is a pair of buttocks’, Museveni matako butako. The matako butako ceases to be important and the relationship it has to Museveni and what he said, what he’s done in Uganda, the context within which the metaphors of vulgarity are used becomes more important, the meaning, the representation, the interpretation, the symbolism.

Often, I use vulgarity as a means to communicate something that I think has failed to be communicated by other modes of language. I think that in the repressive situation of Uganda, where I write from, polite talk has been domesticated, has been bashed, smashed, conquered, it is powerless. It doesn’t communicate with the oppressors. But vaginas and buttocks and penises and vulgarity, whatever it is, whether it’s written or enacted, communicate much better.

Esther Mirembe: We’re almost out of time, but my last question for you is: what is your vision of freedom? What does it look like for you?

Stella Nyanzi: My vision of freedom, wow. Having been locked up in prison for fifteen months because I exercised my freedom of expression that is constitutionally provided … freedom first and foremost demands that there will be no reprisal, there will be no punishment, one will not be penalised for doing what one must do. Freedom for me must entail protections from punishment by authoritarians who choose to limit the freedom that is provided in constitutions and human rights.

Freedom to self-determine is also important. I have been part of the opposition in Uganda long enough to know that people will want us to be free to the extent that they want us to be free, you know what I mean?

Esther Mirembe: Yeah.

Stella Nyanzi: So the opposition members will want me to be one of them as long I’m criticising the other people and not criticising us ourselves as the FDC [Forum for Democratic Change]. And when I do that they say, Nyanzi should not be talking about unity in Uganda as an FDC member, we should ask her to leave FDC. Why? Because she is insisting that the opposition must unite. When I was condemning Museveni for being a traitor and a dictator, they were celebrating my freedom of expression, but the minute I said that FDC has to unite with other opposition parties, then my freedom of speech is being taken away from me and being determined and limited, in fact, by my own opposition members. It is as if one is saying that the terms of my freedom have to be dictated to me by others.

And I’m saying no, actually, freedom means I should decide for myself what I want to be, I should identify for myself what I want to be and I should have the freedom to associate with others who may not necessarily agree with the entirety of how I identify myself, compose myself, constitute myself.

Freedom is about self-determination; freedom is about even those who claim to be in the freedom movement, if there is such a thing. Even those of us there should be self-reflexive, self-critical, and try not limit the freedoms of others or determine for others what freedom should look like. Those are two points. How many did you want?

Esther Mirembe: Any that you have.

Stella Nyanzi: Freedom should also be intersectional, meaning it’s not just about politics in Uganda but everywhere in the world. It’s about feminism, gender equity, gender equality, and not just for men and women but also transgender people and other gendered people. And it’s not just about gender and politics, it’s also about food and hunger and access to dignity and livelihood. Like, why is it that many boda boda men don’t have food today? Freedom should be that we should be able to ask questions about income and income gaps.

I think that freedom shouldn’t be given to us by governments and other hierarchical systems. We must find alternative ways of fighting for our freedoms, especially those of us who live in repressive times and repressive societies. The idea that my freedom is given to me by the government is highly … I don’t like it. Why should the government be giving me anything, especially if it’s a government that I don’t trust? How does a military dictatorship determine what sort of freedom free people have? They cannot, because they’re militant and they’re not a democracy. So how do people think that Museveni’s government is going to determine for us freedom? It can’t.

I think freedom for me then becomes a search. What are the alternative ways in which organised society can claim its freedom? Things such as the bill of rights, the universal declaration of human rights, are a very good starting point in democratic societies, but in spaces such as ours where democracy is an illusion, I think that we should begin organising and resisting and finding for ourselves and creating for ourselves, fashioning for ourselves alternative sources of freedom away from the government. Do I sound mad?

Esther Mirembe: I agree with you.

Stella Nyanzi: And I’m not an anarchist. I’ve been called an anarchist. I actually believe in authority. I just don’t think that it has to be hierarchical like it is in these dictatorships in which we live in Uganda.

- Esther Mirembe is a Center for Arts, Design + Social Research fellow (2020). They are a writer whose work has been published on Africa is a Country, Literary Hub, AFREADA, Africa in Words and African Feminism. They are also the managing editor of Writivism.

About the book

Winner, 2020 Oxfam / Novib PEN International Award for Freedom of Expression

Nyanzi is a hero. Her insistence on violating patriarchy’s rules by talking explicitly about taboo subjects-be they the president’s buttocks, sex, sexuality, queerness-should be studied everywhere as a masterclass in the power of refusing to obey the rules of ‘politeness.’—Mona Eltahawy

Through her actions, Nyanzi has shown that fighting for a free, democratic and equal Uganda does not come free. […] Her story is one that reminds Ugandans that the struggle for freedom has never been achieved by playing to the standards of civility set by those in power.—Rosebell Kagumire, editor, African Feminism

Stella Nyanzi was arrested on 2 November 2018 for posting a poem on Facebook that was said to cyber-harass the long-serving President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni. She was convicted and sentenced to eighteen months in jail.

At the date of publication for this poetry collection, Nyanzi was still incarcerated. She wrote all the poems in this collection during her detention. This arguably makes her the first Ugandan prison writer to publish a poetry collection written in jail while still incarcerated.

The first batch of the poems was released on her forty-fifth birthday on 16 June 2019, which she celebrated in jail, under the hashtag #45Poems4Freedom. Other poems were written after the birthday.

These poems must be read not only for their beauty and the power of the poet’s vision, but also for the bravery and radical intent of their writing and publishing.

2 thoughts on “‘I was anticipating that it would be banned before we even got it out’—Stella Nyanzi chats to Esther Mirembe about her prison poetry collection No Roses from My Mouth”