In Born Freeloaders, Phumlani Pikoli seeks to provide a meditation on how empire is constructed through language. But the language in the book itself can let the writer and multidisciplinary artist down, writes Khanya Mtshali.

Born Freeloaders

Phumlani Pikoli

Picador Africa, 2019

Born Freeloaders, the debut novel from writer and multidisciplinary artist Phumlani Pikoli, has been billed as a meditation on the excesses of young black affluence in the suburbs of Pretoria, a city whose mere mention once struck fear into the hearts of South Africans relegated to a life of violence and alienation in their own land. In an interview with Theresa Mallinson in the Mail & Guardian, Pikoli said he wanted to write about a book about ‘assimilation [and] colonial takeover’, using language as the primary means to explore the price paid by socially mobile black South Africans who threw themselves at making the most out of the Rainbow Nation.

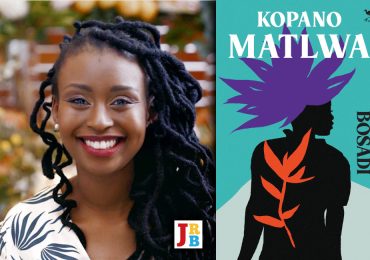

For that reason, Pikoli’s Born Freeloaders has an older sister in Coconut, the bestselling novel by Kopano Matlwa Mabaso, published in 2007. Both books feature some parts of Pretoria, with their central theses exploring the idea of whether young black South Africans can truly be themselves if they are disconnected from the language, culture and mores of their parents. While Pikoli tackles this question in a more compelling way than Matlwa Mabaso, Born Freeloaders, despite its terribly cool name, falls victim to the issues that commonly plague novelists who write in the allegorical. It is free from the elementary errors that made Coconut, and indeed Pikoli’s own 2016 collection of short stories and drawings, The Fatuous State of Severity, a frustrating read. But like Matlwa Mabaso, Pikoli sometimes struggles to create characters with a real sense of interiority, despite the rhetorical flourishes on display in his second book.

With a couple of exceptions, the characters in Born Freeloaders either speak in parables or wisecracks, perfectly timed before they have to exit stage left. This makes it challenging for the reader to push through certain parts of the book; it can feel like reading a script of memorable guest appearances, as opposed to examining the complexities of living, breathing, flawed and broken human beings. Much of the novel’s action takes place over a single weekend in what we can assume are the early twenty-tens. The exploits of this cohort of mostly black, upper-middle-class teenagers and young adults are revealed in scenes that feel like a skit or a routine. One gets the sense that Pikoli believes these characters are engaging in reckless and debauched behaviour. However, under the slightest bit of inspection, their activities are revealed as misadventures typical of the kind of teenagers one would find in Young Adult fiction, or overhear in a random conversation at a mall.

Some of the book’s problems lie in its relative lack of structure or plot. This isn’t to suggest that novels cannot exist without these, but in the case of Born Freeloaders, one does feel that the book could benefit from more of both—even if just to ensure that the characters are able to grow, expand and surprise us within the confines of a lucid, tightly controlled story. Pikoli jumps from scene to scene very quickly for a novel of this length, sometimes forcing the reader to revisit sections in which the action has been breezed past. On the other hand, a fairly heavy reliance on backstory sometimes slows down the pace and energy of the novel, contributing to its occasional lack of focus.

Nthabiseng and Xolani are the siblings at the heart of Born Freeloaders. They share the same black mother, but Nthabiseng has a white father, while Xolani has a black father, about whom we are not given much information. Despite serving as our protagonists, Nthabiseng and Xolani register as standard archetypes familiar to the young, overeducated and terminally online, as the writer Rosa Lyster stylishly put it. This is especially the case for Nthabiseng. We recognise these characters not because they move or stir up something in us, but because we’ve seen them, or versions of them, circulating on social media, or in the cultural production of creatives who mine those platforms for ideas and content.

As we get to know Nthabiseng, it is clear that she derives her ‘complexity’ from straddling two identities, in a place where she is often othered, questioned and assumed to have little connection to her blackness. In one passage, Nthabiseng’s friends laugh at her when she speaks Setswana to a waitress at a Wimpy restaurant because they have never heard her, they remark, speak ‘a black language’. While Pikoli describes Nthabiseng’s slight irritation and awkwardness after this scene, he does little to tease out why Nthabiseng feels such unease speaking a language that she clearly understands and has most likely heard all her life. One could explain her discomfort by simply pointing at her white father, her upbringing in a predominantly white space, or her mother’s tireless efforts to give her children an allegedly better life by encouraging their total assimilation.

But her lack of ease, at least to me, seems to be bound up in a word that feels distinctly South African—shame. Shame at her alienation from the language and customs of her mother, shame at her inaction in remedying what will probably be sore point for the rest of her life, shame at being an outsider among people who have loved and cared for her in ways that her father’s family, we assume, would never have. Instead of pushing for an explanation that could deepen our understanding of Nthabiseng’s internal conflict, Pikoli opts to sketch out, predictably, her alleged complicatedness. He uses her gendered mixed-raceness as a device; it is intended to establish her as the novel’s ‘messy’ character without making the effort to skewer her relationship with her identity, in the same vein as Danzy Senna in New People or Fran Ross in Oreo. Unfortunately, Born Freeloaders expects us to accept that Nthabiseng, who we have now registered as a tragic mulatto figure, is ‘troubled’ because she fails to respond to her mother’s texts during and after groove; she smokes weed with her friends; she is quick to replenish her drinks at parties; and she bums cigarettes off people because she is the type to start smoking when there is alcohol involved. These details are so overdramatised that one wishes to point out to Pikoli that in a world where our social lives are oriented around drinking, where it is easy to ignore texts from people we care about because of how widely accessible technology has made us, Nthabiseng’s behaviour is fairly quaint and ordinary.

Xolani, on the other hand, is the ‘alternative’ frontman of a band called The Cursed Children of Ham. We are informed that he has white girlfriend, Bell, to whom he seems mostly indifferent, if not hostile. He feels cheated by life because he believes his talents have yet to be recognised by the world, despite the modest success The Cursed Children of Ham have enjoyed. And he craves the validation and approval of his Uncle Zweli, whom I will return to shortly, because he is the only visible father figure in his life. He wants to be taken seriously as a musician but appears damned to a life of obscurity.

Early in the book, Xolani becomes demoralised at a scathing, overwrought review penned by a snobbish white music journalist who calls bullshit on the band, accusing them of using their position as black men playing supposedly white music to promote ‘the same bullshit PC internet politics and catchphrases that the woke circle jerks are waiting to jizz for’. The use of the term ‘woke’ in the article is curious—it threw me off. Near the end of the novel, Pikoli describes a character named Thami sitting in the back of a shuttle with Nthabiseng’s friends, who are belting out ‘Young Wild and Free’, a song from ‘one of [these] new rappers’, Wiz Khalifa. The song is from 2011; ‘woke’ only started gaining traction among the wider white public in 2015—possibly 2016—and probably even later for the bulk of white South African public. It is a tiny detail but it should be observed, because the internet’s history of absorbing and debasing language, terms and culture founded by black people cannot, in a novel about identity, language and youth culture, be overlooked. While the rest of the band is unbothered by the review, it stays with Xolani. One feels his resentment mounting as he tries to drink and smoke away pangs of insecurity and self-doubt. His thoughts drift into the past, where he reminisces about Cursed Children escapades, recounting a story involving a trip to Nelspruit and taking psychedelics with an Afrikaans band in a management-organised, Run-DMC-meets-Aerosmith-style collaboration.

However much we sympathise with or roll our eyes at Xolani’s sense of being misunderstood, the feeling is fleeting, because his character never firmly establishes itself. More surprisingly, we don’t ever get a sense of what The Cursed Children of Ham actually sound like. The convoluted, snarky review from the white music journalist offers some clues—’bunch of African children that the Parlotones adopted’, ‘gutless Rebecca Black knock-offs’ and ‘The Strokes playing through a stroke’ are fairly delicious cuts—but given Pikoli’s obvious interest in music, it would have been nice to have a sense of the band’s sound. I could not help but wonder who was on drums, bass or guitar? Were there any synthesisers or keyboards involved? Given how much Pretoria remains criminally overlooked when it comes to acknowledging the city’s contributions to South African music, the omission seems an opportunity lost.

Interestingly, it is the minor characters in Born Freeloaders who most capture our imagination. Uncle Zweli, who was a freedom fighter in exile, becomes somewhat of an Every Uncle, representing a particular kind of older male relative whom you would encounter in a number of black South African households. He moves into Nthabiseng and Xolani’s home when she is four and he is eight, staying there ‘for some time’. He smokes ‘special cigarettes’ which make him ‘ramble incoherently’ or ‘giggle to himself unexpectedly’. And he looks down upon his niece and nephew because they do not seem to have any appreciation for his efforts to dismantle an unjust system. He calls them ‘the children with no tongues’, setting up the premise for the novel and expanding upon it in a lyrical passage several pages later:

‘Do you not get tired of wondering what people are saying all the time? Not fully understanding any language you speak? To not be able to laugh at a joke with complete certainty that you understood its full meaning, rather than observing social protocols? To not always wonder whether you’re the butt of it or not? I really don’t understand; you seem to take pride in your ignorance instead of being ashamed enough to ask more questions to learn about yourself.’

Here, Pikoli channels the high allegory of anti-apartheid writers like Athol Fugard, Alex La Guma, Zakes Mda and Es’kia Mphahlele. The passage may read as clunky and moralistic to the more modern, fable-averse ear, but it functions as an effective revelation of Uncle Zweli’s values and thus the values of an older generation of black South Africans. In addition, our Every Uncle inadvertently brings up another idea that isn’t as widely discussed when it comes to young black South Africans who are ‘divorced’ from their own language and culture. What Uncle Zweli’s monologue reveals is that Nthabiseng and Xolani not only feel alienated by the language and customs of their parents, but they are also alienated from the English-speaking Western culture in which they are immersed, but will never fully belong to or understand. They experience a sort of double isolation, which they make up for by forming their own slang and language that sits in between that of their parents and that of their school environment and social group.

The character who best showcases the subtlety and wit that Pikoli occasionally attains in Born Freeloaders‘ most convincing moments is Thami, the gangly outcast who is besotted with Nthabiseng but hasn’t summoned up the courage to make that clear to her. If one were to search for famous peers for Thami in film and television, one could look to Josh Lucas from Clueless, Michael Moscovitz of The Princess Diaries, Navid Shirazi in the rebooted 90210 and Dan Humphrey from Gossip Girl (who now plays the homicidal version of that character in the Netflix series You)—classic good guys who can’t catch a break because the women they love don’t notice them. This is a great crime, which they place squarely at the feet of a superficial society that favours more traditional forms of masculinity to their quiet, bookish ways. But of course, we know it is misogyny that allows these men to feel like lifelong victims because women have rebuffed their advances. And while the rest of us have managed to survive rejection, they play righteous and wronged until a woman inevitably comes to their senses and gives them a chance. Finally, some justice!

Thami strikes a more complicated figure than this, however, even though we suspect he holds the same views and attitudes as his Hollywood contemporaries. He takes a strong disliking to Nthabiseng’s friends, but is clever enough not to mention that to her, lest he loses their vague relationship. What is captivating about Thami is that he embodies the trivial yet profound pain of having the world reject or ignore what you think are the most sparkling parts of yourself. He isn’t furnished with the weighty backstories of our sibling duo, yet he leaves the most lasting impression on the reader. Against our better judgement, we feel for him, as he fails to make an impression on the self-involved, self-important people who are best mates with the woman he wants so badly. In the latter part of the novel, where dialogue and scene are the strongest, Thami fumbles as he is roped into an afternoon that he never signed up for because of Nthabiseng’s selfishness. He embarrasses himself constantly, failing to identify a bellini, getting teased for his bohemian, artboi plans of wanting to travel across the country and take pictures of unassuming civilians going about their day, and barely surviving a conversation with Siya, the resident jock and rugby captain who most likely relaxes his hair, wears white loafers and will attend Matric Vac well into his twenties.

We side with Thami through most of this, but Pikoli does not let our sympathies run unchecked. Thami is capable of the same ignorance as his peers, except his goes under the radar because he presents as harmless and unassuming. After taking Nthabiseng to a cypher in Sammy Marks Square that he regularly films (because he is that guy), he recommends they head over to Marabastad to ‘get some interesting photos and footage there’. He makes the mistake of having this conversation in front of Tsholo, a sadly underused character in the book who reminds one of that YFM/Y Magazine era when black women listened to neo-soul, sported dreads and wore chunky jewellery and kaftans. When Thami informs her of their plans, she smirks, telling Nthabiseng and Thami, both model C kids desperate to get a taste of ‘authentic’ black life, that they’re engaging in poverty porn not too dissimilar from those voyeuristic township tours or ‘street style’ fashion shoots where influencers take photos in front of a spaza shop or a tavern. This warning mostly flies over their heads, but it reveals that Thami is no ‘better’ than Nthabiseng and her friends, despite what he may think. Pikoli illustrates that Thami’s status as an outsider does not exonerate him from participating in the same hypocrisy for which he judges Nthabiseng and her friends harshly.

As the born-free generation has become emboldened to criticise the concept of Rainbowism, Pikoli’s Born Freeloaders offers a literary answer to the deep scepticism that reached its zenith, at least for the young, black and English-speaking, with the Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall movement. The novel’s attentiveness to these timely themes may afford it the kind of cultural relevance that makes some books seem more urgent and interesting than they actually are. But Pikoli’s assembling of this coalition of topical South African issues can get in the way of his less politically on-trend gifts as a writer. There is no denying the power and thrill in seeing one’s experiences, identities, way of talking, friends and family members symbolically represented in the world of letters. But Born Freeloaders prompts us to ask, How long will this be enough? When the warm familiarity of representation fades, what sort of literature will we gravitate towards and produce? In the case of Born Freeloaders, the answer to that question, much like the future of our democracy, remains to be seen.

- Khanya Mtshali is a writer and critic based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.