The JRB Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela travels to Ethiopia with the living archive of Maaza Mengiste’s novel, The Shadow King.

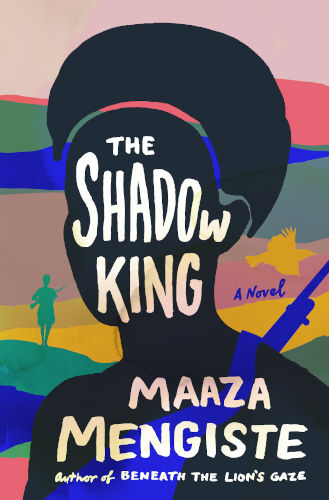

The Shadow King

Maaza Mengiste

WW Norton, 2019

A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.

—Diane Arbus

The Shadow King is Ethiopian–American Maaza Mengiste’s second novel, arriving nine years after her celebrated debut, Beneath The Lion’s Gaze. The narrative is non-linear, hopping back and forth between eras, but we find ourselves mainly in 1935 Ethiopia, just before the start of the Second Italo–Ethiopian War. The aspiring colonisers expect an easy victory but get a lot more than they bargained for—in part due to woefully underestimating Ethiopia’s women.

Men are useless in this war. Mengiste’s genius rendering of Emperor Haile Selassie (in interludes interspersed between the main storyline) is as a remote patrician, with a conscience muffled by luxury. The gloomy Shadow King is both obsessive and aloof; fixated on his grand persona yet indifferent to his people’s suffering, as if convinced they won’t remember, or certain that the Italians will kill them anyway. Selassie retreats long before the Ethiopians are ready to surrender, repairing to Bath in the United Kingdom, while on the ground militias fend off the occupation. They attack the Italians in small groups from the hills in this people’s war. Mengiste researched historical battles extensively, saying in The Wall Street Journal, ‘I was looking for historically accurate, mappable geography that could exist alongside the fictive terrain where my characters woke, slept, fought and loved.’

One of these militia groups is ‘organised’ by Kidane, a senior officer in Emperor Selassie’s army who rules over his household with a cruelty he confuses for leadership. Once in charge of the militia, his vicious streak is exposed, his courage flickers and the women in the book with their discipline and wisdom come to prominence. Aster, his wife, dons an imposing cape and leads the women warriors in formation. Hirut, a housemaid, is the youngest and feistiest of them—a heroine. When Kidane steals her most precious possession, her father’s antique Wujigra gun, from her, she receives her first lesson about the broken promises that hide below the bluster of war. It causes:

… the first thread of sourness [that] curls inside of her, pungent like rot, so tiny she chooses to mistake it for the distant smell of smoke.

Mengiste’s writing is bard-like and flowing, with an all-knowing chorus that breathes a new perspective into key moments. Although the story and its telling is indebted to Greek and Roman classics, Mengiste eschews the lengthier battle scenes found in the epics. She shifts focus often to the more subtle war between the Ethiopians and the lens. Ettore Navarra, a Jewish-Italian soldier, is part of the invasion, his camera his weapon. He documents Italy’s advances, the bloody-mindedness of Colonel Carlo Fucelli and the shame of the prisoners of war. The camera’s gaze is unflinching as Hirut, once captured, discovers:

There are horrible things that the Italians do to girls, but no one has warned her about the interlude between discovery and death, between recognition and assault, that stretch of time when anything and everything is possible and all the frailties of the body are exposed to merciless light.

But sometimes cameras lie. One of the central concerns of the plot is the recorded sighting of Emperor Selassie in Ethiopia when he is reported to be overseas. Who then is this Shadow King? And what else are the Ethiopians conjuring up?

Navarra’s photographs pace the course of the story and show the gap between reality and what is recorded, how images can sometimes be poor shadows of what transpired, or how they can bind both the subject and the photographer in life-long tension. Mengiste explores each image in vivid descriptions, each detail within the corners—a cunning posture, a tense plait, a demure chin. It fools us into thinking we are not alone with a book in a corner of the house but leafing through the personal archive of a dedicated rememberer, thrilling to the layered, secret nature of it.

It’s clear that the act of writing The Shadow King is reclamatory—perhaps a more fiction-leaning form of what Saidiya Hartman calls ‘critical fabulation’, using fiction to surmount the boundaries of the archive. Mengiste herself says:

Not everything survives, but what does might just be strong enough to honour what could not.

This mirrors her author’s note, which mentions that the inspiration for the book was the real story of her great-grandmother, Getey, who enlisted to fight in the war.

In her rousing 2018 Abantu Book Festival keynote address on ‘Archival Fever’, legendary publisher Bibi Bakare-Yusuf urged:

We have to stop thinking of the archive merely as that which is past, we have to think of it simultaneously as past, present and future. We have to think of the archive as a curation of knowledge, experience and worlds in the now, to help order a past for the purpose of the future.

The Shadow King fulfils that mission, and pulses with the same delightful fever.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing Editor Efemia Chela on fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the tenth article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.

One thought on “[Temporary Sojourner] Thrill to the layered, secret nature of it—Efemia Chela reviews Maaza Mengiste’s new novel, The Shadow King”