Hip Hop is producing a new generation of readers and writers in a world that operates in diverse literary forms, writes Marlon Swai in Neva Again: Hip Hop Art, Activism and Education in Post-Apartheid South Africa.

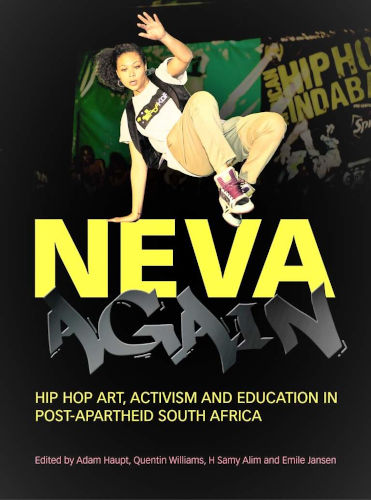

Neva Again: Hip Hop Art, Activism and Education in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Edited by Adam Haupt, Quentin Williams, H Samy Alim and Emile Jansen

HSRC Press, 2019

About the book

Neva Again is the culmination of decades of work on Hip Hop culture and Hip Hop activism in South Africa. It speaks to the emergence and development of a unique style of Hip Hop activism in the Western and Eastern Capes.

The book draws on the contribution of Hip Hop scholars, artists and activists, and weaves together the many varied voices of this dynamic Hip Hop scene to present a powerful vision for the potential of youth art, culture, music, language, and identities to shape our politics.

The excerpt is taken from Chapter 12, ‘Pedagogies of the Formerly/Formally Oppressed: Hip Hop Education In Cape Town’ by Marlon Swai.

~~~

Read the excerpt:

Reading the word and the world

The English term ‘conscientisation’ originally derives from Frantz Fanon’s (1967) adaptation of a French word, conscienciser, in his book Black Skin, White Masks. Paulo Freire eventually popularised the concept in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed, originally published in 1968, which was quite specific to the Brazilian context but included a theoretical framework around critical consciousness, conscientisation or conscientização (Portuguese), which is universally applicable to situations in which an individual obtains a comprehensive understanding of the world that allows for the discernment and uncovering of sociopolitical contradictions. Importantly, critical consciousness also entails translating this understanding into action against the oppressive aspects affecting one’s life (Mustakova-Possardt 2003). As such, Freire found formal education systems in his context to be sorely lacking and his critiques thereof resonated widely, not least in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s.

While some consider Hip Hop to be antidotal to formal education, most artists and programmes that I know of do not encourage youth to turn their backs on school. Take the late great Cape MC, Mr Devious aka Mario van Rooy (RIP), for example. To him, the cultivation of a sharp intellect was the primary way for a young man to survive the odds that are stacked against him. His songs are riddled with appeals to the youth to stay in school and pursue education in addition to taking a critical stance towards it. Consider these lyrics from his 2006 song ‘Still Breathing’:

To the youth, stay in school keep on breathing

Stay motivated, keep on believing

higher learning’s how you reach your achievement

Devious recognised that ‘school’ is part of a larger world for which youth need navigation skills. Crouching at a street corner, surrounded by dreadlocked compatriots in his home township of Beacon Valley, the 2006 bio-pic Mr Devious: My Life shows him saying:

We not good guys, we not bad guys

We are somewhere in the middle

We the balance between negative and positive

We can switch at any moment

So to maintain that balance we have to be conscious of what we see around us

and how it affects us and our people

‘To be conscious of what we see around us and how it affects us and our people’ means to develop a certain literacy with which we can ‘read the world’ in order to become active agents within it. Freire’s notion of ‘reading the world’ posits the world as text that can only be deciphered through a critical kind of literacy. A major ‘literacy skill’ is the ability to see one’s self in (con)text while also activating one’s agency to write and rewrite this text. Literacy thus means much more than the ability to read; it means learning to read and reading to learn. Literacy includes writing and rewriting, seeing, observing, but also interpreting and intervening. Literacy means access to the world in the first place; it fundamentally alters consciousness and irreversibly changes our ways of knowing, how we process information and how information processes us. Critical literacy complicates, but also demystifies, the power to write versus the power to read, and the power to produce versus the power to consume knowledge. Being ‘conscious of what we see around us and how it affects us and our people’ directly speaks to the difference between seeing versus comprehending how the seen affects us, shapes us, (in)forms us.

Critical literacy thus demands at least two levels of decoding. This decoding of multiple layers of reality is a skill that I distinctly learned through my engagement with Hip Hop as a youth. Then we all entered the age of mass mediation technologies, now oral traditions have transcended and transmuted clan, village, skeem, kasi¹, borough, hood or block in the context of endless mass-mediated sodalities². We are now dealing with a global public literary environment that meshes so tightly the ‘real’ and the ‘simulation’ that the frequency, intensity and reach of the reading and writing practice of more and more individuals means we’re increasingly spending time engaged in multiple and multimodal acts of literary production and consumption. Whether we’re reading or writing pages (inked or Instagramed), listening to or conversing with sages (on stages or SoundCloud) or skimming or scribbling on walls (temple, toilet or timeline), we are producing knowledge even in the act of consuming it. Positioned between tough circumstances and the possibilities opened up by the pursuit of artistry, Mr Devious articulated the nuances involved in existing in the interstices between street life and poetry, between a life seemingly overdetermined by history and economics and the agency to change it, and he reinterpreted these nuances emphatically so his audience could understand the stakes.

Dialogic action

Freire argued that through the process of communication about what we see and how we see, we produce and reproduce ourselves through being in perpetual dialogue with others. According to his theory on dialogic action, the educator must make a choice between dialogue and non-dialogue. For Freire, to choose dialogue is to endorse critical learning, and in order to do this, the educator must foster the circumstances for dialogue to occur that animate the learner’s epistemological inquisitiveness. Hip Hop is increasingly being recognised as an indispensable tool for creating the kind of learning environments that stimulate learner curiosity and nurture pedagogies that are not only culturally responsive, but also culturally sustaining (Paris & Alim 2014; Petchauer 2009; Runell hall 2011).

The objective of dialogic action is to constantly expose the truth through interrelating and interacting with others. Relatedly, Hip Hop education has emerged in the last two decades as a key strategy for bringing the world of the students into the classroom and for inspiring self-regulated learning outside of it. In his dialogic action theory, Freire emphasises the difference between dialogical actions, which stimulate empathy and insight, cultural invention and freedom, and non-dialogic actions, which negate dialogue, distort communication and replicate uneven power relations (Freire 1970). Of course, Hip Hop is equally capable of non-dialogic actions, but again and again it proves to be a set of practices that are endlessly generative for promoting dialogic action.

ALKEMY

ALKEMY was a programme hosted by Bush Radio between 2000 and 2007. Explicitly leaning on Freire’s contributions, its aim was to train participants in actively reading and rewriting the world. ALKEMY used music, and Hip Hop in particular, as a means to facilitate the imagining and reimagining of social change. Through a series of seminar sessions, workshops, field trips and a mentorship component, the programme prepared youth for active participation at the civic level, but also for meta-cognitive and self-regulated learning. ALKEMY conscientised youth by proposing a critical lens through which they/we could deconstruct some of the information they/we were receiving in the media and their/our environment, including school.

There was a strong focus on developing close reading skills and producing both creative and analytical writing. The syllabus included texts like Manufacturing Consent (1988) by Edward S Herman and Noam Chomsky, Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1967). A unique feature of ALKEMY’s pedagogic approach was to elicit connections between Hip Hop albums and the readings. It so happens that several albums are named after texts, for example, Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe’s famous novel, inspired the Philadelphia-based Roots crew’s 1999 album of the same name. Chicago’s Common called his album Like Water for Chocolate (2000) after Laura Esquivel’s 1989 novel, while Bone Thugs-n-Harmony’s The Art of War (1997) made reference to Sun Tzu’s philosophical treatise. Tupac’s The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory invited listeners to find out more about The Prince and Other Writings by Niccolò Machiavelli (2003). ALKEMY took advantage of these book–music pairings in order to make reading more attractive to youth who were already hooked on the music. ALKEMY participants would read these rather advanced texts, discuss them in both facilitated and informal settings, and usually a writing module would bring exposure to a text full circle, for it is through writing that one deciphers text, extracts the lessons most applicable to one’s own world, and it is through writing that one inscribes oneself into the world of the text, making its innermost insights knowable. A long-standing member remembers a part of the process:

ALKEMY … provided us with tools that prepared and taught me to navigate the world around me. It was in those sessions that I first heard of agency … it never made sense until I started applying it to my world. (Oko Camngca interview, 2016)

Oko’s twin brother Ade spoke in more explicit terms about the way in which the programme provided him with tools to read and reread:

In retrospect I saw the programme as a ‘legacy project’ that was reminiscent of the [underground] youth struggle movements of the ’70s and ’80s. I saw this programme as a continuation of this [political activism] ‘tradition’—because it challenged what I was taught by providing an alternative narrative that was more plausible than what could be found in the prescribed literature of government schools; again, this doesn’t mean all the literature was bad, but made me think why were we made to read The Great Gatsby instead of Things Fall Apart—subversive cultural domination at its best … (Ade Camngca interview, 2015)

During my participation in ALKEMY, as with my brief involvement with programmes like a series of comic-book writing workshops at the District Six Homecoming Centre, or the Young in Prison’s lyric-writing workshop series or, most recently, the INKredibles workshops presented by the Stellenbosch Literacy Project (SLiP), and during numerous interviews and conversations, an underlying theme is the intention to produce a new generation of readers and writers of the world that operates in diverse and multimodal literary forms, including dance, visual arts and other forms of scholasticism. In order to address the deeply systemic problems facing their constituents, these programmes provide training in visual literacy, media literacy, political literacy, transcultural and diasporic literacy, and more. With this multisensory approach to ‘reading the world’, these projects not only complicate public discourse in a context of hegemonic media culture, but also provide their participants with the means to inscribe themselves into—i.e. reread and rewrite—the world.

The programme facilitators and developers of ALKEMY used the word ‘conscientisation’ in a direct nod to Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. ALKEMY facilitators were both aware and mindful of Freire’s (1970) ‘banking concept’ of education, which he used to critique how formal education treats learners like blank slates and empty vessels needing to be filled. Rather than recognising and building on students’ prior knowledge, their life skills and their diverse interests and expertise outside the classroom, the banking model assumes that information can simply just be ‘deposited’. Freire argued that the ‘banking’ approach to education will never ‘propose to students that they can critically consider reality’ (Freire 1970: 61).

Notes

1. ‘Skeem’ and ‘kasi’ are distinctly South African terms which function in much the same way that the word ‘hood’ does in the US. They signify the discursive reclamation of geopolitical spaces and places inhabited by marginalised communities. Just like ‘hood’ is appropriated from the word ‘neighbourhood’, skeem has its origins in the notion of the housing scheme and kasi is from lokasie, the Afrikaans word for location, both designated for black and coloured communities under apartheid-era legislation.

2. For Arjun Appadurai (1996), the onset of the age of mass media has amplified the messiness that historical mass migrations have caused for the idea of nationhood and nationalist conceptions of citizenship. This messiness is represented by ‘mass mediated sodalities’, vast groups of people whose experiences of belonging and affiliation beyond the nation state are facilitated by mass media.

~~~