This year marks one hundred years since Peter Abrahams’s birth. Elinor Sisulu reflects on her meeting with the author at his home in Jamaica.

When I came to Jamaica, when I found this place, I knew, my search was over. You see, until I came here, I was the ex-patriot. The migrant, and you know, they live with suitcase packed, ready to go home. But when I got involved in Jamaican life, in Jamaican politics, when I travelled this island … I became involved, and this was the first time in my life I didn’t have to be against anything, I could be for something.

—Peter Abrahams, The View from Coyaba (documentary)

I think I’ve had a hell of a lot. I’ve seen all of Africa free. I’ve seen South Africa free. I had no right to deserve that. So what should I bawl about?

—Peter Abrahams, The View from Coyaba (documentary)

One of my new year’s resolutions for 2019 was personally to celebrate the centenary of three iconic South African writers, Peter Abrahams, Es’kia Mphahlele and Noni Jabavu, by rereading their works. Like most new year’s resolutions, this one has fallen somewhat by the wayside, but I have at least made some headway with the works of Peter Abrahams, mostly because I am blessed with a personal connection.

In 2007 I had the good fortune to secure a fellowship from the Prince Claus Fund to spend time at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies at the University of the West Indies. I was based at the St Augustine campus in Trinidad but did have time to visit the Cave Hill campus in Barbados and the Mona Campus in Jamaica, where I was hosted by Dr Leith Dunn. I could not have fallen into better hands. Apart from being the head of IGDS at Mona, Leith was active in the Jamaica South Africa Friendship Association, which was at the time chaired by her husband Professor Hopeton Dunn. She organised a stimulating and enjoyable programme that included a meeting with a group of Jamaican children’s book writers and members of the Jamaica Reading Association, an interview on Beverley Manley’s acclaimed morning radio talk show, an interview with Jamaican storyteller Amina Blackwood-Meeks, a visit to the Bob Marley museum and a fabulous lunch under a giant mango tree, with United Kingdom-based educator Dr Greta Akpeneye and local attorney Maurice Frankson.

As fascinating as all these experiences were, though, the highlight of my Jamaica trip was my visit to Peter Abrahams.

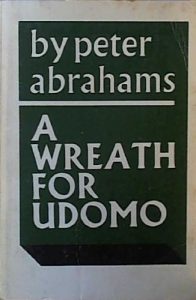

When I included the name of Peter Abrahams on my wish list for the trip, I scarcely believed that it could happen. Having gone to high school in colonial Rhodesia, the first novels by African writers that I read were those prescribed in our English literature course in my first year at university: Peter Abrahams’s A Wreath for Udomo and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood. As a student of African nationalist history, I came across him again in his role as one of the moving spirits of the Fifth Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester in October 1945, and found it fascinating to analyse how the historical figures informed the fictional characters in A Wreath for Udomo. Peter Abrahams was therefore a figure of mythological proportions in my mind, who stood at the intersection of literature and history.

Du Bois had Pan-African conferences, where a group of intellectuals, some French Black intellectuals, some American Black intellectuals, would come together, many of them who’d never been to Africa, but speak for African freedom. And then finally, under George Padmore’s guidance, in 1945 we have the first legitimate Pan-African conference, the Fifth Pan-African Conference, where you had delegates from all over the world, and this was the most representative gathering of African delegates, meeting in London, the world had ever seen. They weren’t just, as had been before, ‘speaking for ourselves as agitators’, saying ‘Africa must be free’. Now you were representing the continent and the diaspora.

—Peter Abrahams, The View from Coyaba (documentary)

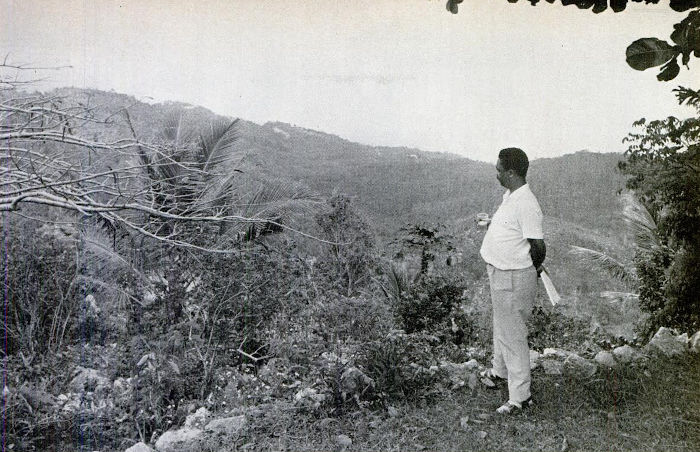

I could not believe my good fortune on that Sunday in April 2007, when Leith drove us to the outskirts of Kingston, and up the hill to the famed Coyaba homestead of Peter and his wife Daphne. ‘Coyaba’ being the Arawak word for ‘heavenly place’. I was welcomed like a long-lost friend, with warmth and curiosity. My first impression was of dusty bookshelves and large colourful canvases. Daphne showed us some of her paintings, which I found fascinating. I had no idea that she was such an accomplished artist. Peter informed me that she had written her autobiography and wondered if a South African publisher would be interested. I said I would be happy to look into it. Daphne then took Leith out to the verandah, with the incredible view overlooking the city, leaving Peter and I in the large living room.

Peter’s first question was about Walter Sisulu and I was proud to present him with my biography of Walter and Albertina. We spoke about Walter’s trip abroad in 1953, when he visited Israel, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and China, ending with a few days in London. Peter recalled his interaction with Walter during the trip and their meeting in London, where Walter met with veterans of the Pan-Africanist movement.

Peter spoke fondly of Oliver Tambo and the pleasure and privilege of meeting Nelson Mandela on his visit to Jamaica. He was interested in the series of diaspora conferences that the South African government had been organising, around the Caribbean, and in London and the United States, as part of its commitment to forging closer South-South links in recognition of the strong historical, political and cultural connections between developing countries, and the shared challenges of survival in a globalised world. I had recently been to the conference that had taken place, on 17 March 2007, in the Dominican Republic. Peter was impressed by then-President Thabo Mbeki’s commitment to investing in links with the diaspora. (Sadly the diaspora project was unceremoniously dropped when Jacob Zuma became president.)

I asked Peter why he had not visited South Africa after 1994, and he said he was too old, and that after twenty years in Jamaica ‘I woke up one morning and realised that I am no longer in exile, I am a Jamaican.’ Despite this assertion, I think that if Peter had been issued with a high-level invitation to South Africa in 1994 as a visiting literary celebrity by one of the major universities, he would have relished the opportunity.

Just before my Jamaica trip I was fortunate to attend the University of the West Indies’ celebration of the acclaimed writer and Nobel Literature Laureate VS Naipaul’s seventy-fifth birthday, an occasion that marked his return to his native land after several decades. The year-long commemoration was capped by Naipaul’s visit, which coincided with a festival in his honour, held from 18 to 21 April 2007, taking the form of a series of lectures by scholars, a book-signing and reading by Naipaul, and a symposium on his work. I was privileged to attend the reading by the great man, held in the huge gymnasium on the St Augustine campus. Naipaul ‘performed’ to a packed audience in an event that was more like a pop concert than a literary reading. I was more interested in the questions from the audience than Naipaul’s responses, as the remarks from the crowd revealed the deep ambivalence that Trinidad had toward one of its most famous sons—not surprising, considering that Naipaul had made no secret of his contempt for his homeland, dismissing it as ‘a simple, colonial, philistine society’.

After Naipaul won the Nobel Prize in 2001, acclaimed Caribbean writer Caryl Phillips recounted the angry response of a Trinidadian audience when he criticised Naipul’s attitude. ‘I quickly understood. Naipaul may be an ungenerous bastard, but he was their ungenerous bastard. Who the hell was I to talk about their son of the soil?’ he said.

While denouncing the apartheid political system, Peter Abrahams never expressed anything but love for the country of his birth and its people. His embrace of a Jamaican identity was never a rejection of South Africa. Yet if he had returned to South Africa post-1994, I doubt if he would have received the same reception that Naipul received in Trinidad. Perhaps this is due to the different value each country places on literature and celebrating one’s own. I had meant to discuss the Naipaul visit with Peter but time was short and he was more interested in talking African politics.

The only discordant note in our conversation was on the question of Zimbabwe. Peter wanted to know whether the reports on human rights abuses in Zimbabwe were not exaggerated by the Western media, and I informed him that, unfortunately, far from being exaggerated, the scale of abuses was far higher than reported. He was saddened by this, and more generally by the failure of postcolonial African states to respect freedom of speech and independent thought.

Throughout the visit I marvelled at the remarkable memory and mental clarity of this man who was just two years short of turning ninety years old. Our conversation was interrupted at some point by a young man who had come in to fix Peter’s email. From his conversation with the technician, I gathered that Peter Abrahams knew more than I did about computers.

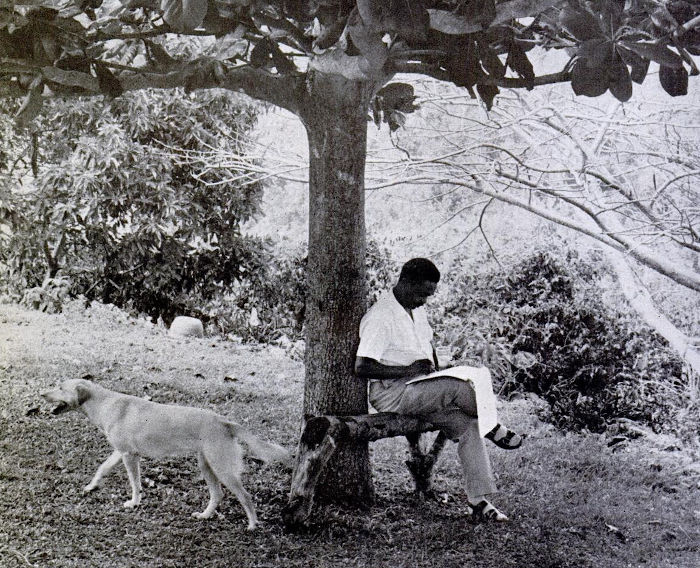

The visit ended all too soon, and as Leith inched her car down the hill, I mentioned that the couple must be having a problem with their water supply, judging from the brimming buckets and small baths I had seen when I went to the bathroom. Leith informed me that running water and electricity were indeed a problem in the area, and that Peter and Daphne lived a simple life, without the perks one would expect from Peter’s global fame and status. This was an oasis for writing, ‘far from the madding crowd’. It was quiet and picturesque, and they had access to technology, which enabled them to keep in touch with the latest news.

A few months after my return to South Africa, I had a phone call from someone from the Presidency. I immediately tensed up. The Zimbabwean in me assumed that the call was in connection with my public criticism of President Thabo Mbeki in the previous week, on his approach to dealing with the Zimbabwean crisis. But apprehension transformed into pleasurable surprise and disbelief when the voice informed me that Peter Abrahams was being awarded the Order of Ikhamanga for his service to South African literature, and had nominated me to receive the award on his behalf, since he was unable to travel to South Africa. I was profoundly moved by the honour, and overjoyed by the recognition for Peter. I received the award and delivered it to Faith Radebe, then the Ambassador to Jamaica, who has sadly since passed on. Ambassador Radebe organised a special event to present the award to Peter and Daphne, which was covered by the Jamaican media.

In the ensuing years, I was in touch with Peter and Daphne a couple of times by phone. Sadly, I could not get any publisher interested in publishing Daphne’s autobiography. There was, however, interest in Peter’s 1954 novel The Path of Thunder. Dusanka Stojakovic, the managing director of David Philip Publishers, which had co-published the book in a new edition in 1984, wanted to republish it as a school setwork. When her attempts to reach Peter to get permission were met with a rebuff, I tried to persuade him to change his mind, without success. When he complained about his experiences of being ripped off by publishers, I suggested that we could get a good intellectual property lawyer to protect his interests, but he was not receptive to the idea, so we had to let it drop.

The last time I spoke to Peter was when I heard from Leith that one of his daughters had passed away. I tried to call him after news of Daphne’s death in 2016 but there was no response. When I heard he passed away in January 2017 I assumed that it was natural causes. I wept when Leith informed me that he had been murdered. It was not fair that his life ended in that way. He should have slipped gently into that good night.

Apart from a tribute by the Thabo Mbeki Foundation and a few obituaries here and there, Peter Abrahams’s death did not receive much attention in South Africa. In his excellent obituary, Brooks Spector questioned why Peter Abrahams had received so little recognition in the country of his birth:

But what comes as a shock to discover, however, is that there apparently are no monuments in his home nation to Abrahams’s great literary achievement. Surely there should be a library named in his honour, an endowed chair in African literature at one of the nation’s premier universities, and a publishing effort reprinting his output in a standard, uniform edition. It is long past time for these honours.

But with nearly three years remaining until the [hundredth] anniversary of his birth, there is time to get things moving, if influential people get behind such an effort. Embracing his memory as an early literary pioneer and impact as a writer must also take into consideration the eclecticism of his political thinking, his influence on the Pan-African idea, and an ethnicity that embraced the near-totality of South African experience.

Sadly, Spector’s clanging hint was not picked up, and Peter Abrahams’s remarkable legacy remains largely unrecognised. In comparison, the University of the West Indies Mona held a full-day symposium in his honour, entitled ‘Celebrating Peter Abrahams 100: Milestones in Literature, Media and Political Commentary’, the recording of which is fortunately available online.

The symposium, organised by Prof Hopeton Dunn, was informative, inspiring, and heart wrenching at times. I intended to watch for a few minutes and ended up sitting up for hours. What touched me most was that, in complete contrast to what one might be led to believe from the tragic circumstances of his death, Peter was not a relic of the past, a lonely old man up on the hillside. He had a community of people around him who supported and cared for him, and he was intellectually alert until the end. Testimony to this was his joy when Barack Obama became President of the United States, and his canny prediction that there would be a backlash and that Donald Trump would win the next election.

Many would argue that because Peter Abrahams left South Africa at the age of twenty, his books banned, and without a return after 1994, it is hardly surprising that the memory of his literacy legacy has faded. In a paper entitled ‘The Long Eye of History: Four Autobiographical Texts by Peter Abrahams’, Stephen Gray notes:

The fact that Abrahams has not returned to South Africa since 1952 seems to have ruptured the scholarly memory, as we know only too well the infrastructure that keeps authors alive—reviews, discussions, lecturing, research, the press and journals—tends only to assert the values of contingencies and current needs. In short, Abrahams of the forties and fifties, the founder of dark testimony in South African literature and the country’s first professional black writer, is no longer meaningful to us. But Abrahams’s work is not only seminal for the variety and sustained standard of his output, but inescapable for its influence—he was the first South African modern to demonstrate the possibilities and potential of black literature in a postcolonial world.

—from a paper presented at Wits History Workshop, 1990.

Gray argues that Peter Abrahams may not be in vogue in South Africa any longer partly because, unlike Mphahlele, his newer work was not obviously and directly South African. But this begs the question of why the centenaries of both Mphahlele and Noni Jabavu were not marked either. I would argue that for all three the lack of attention to their work is more a case of a general lack of interest and investment in literature outside of academic and literary circles.

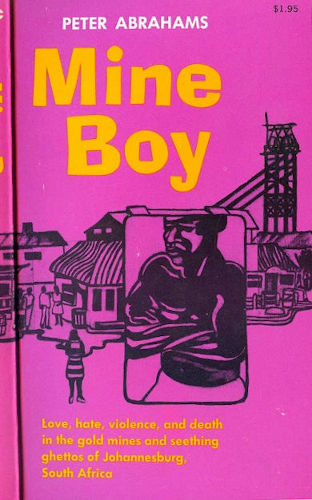

I recently had the honour of being the guest speaker at the annual Jozi Books and Blogs Festival in Lenasia, south Johannesburg. I spoke of the need for a literature of mirrors and windows for young children—the mirror so that the child can see her- or himself in the book, and the window to look out at the world. Literature, like education, should move from the particular to the universal, not the other way around. After my presentation, a Grade 11 student came up to me and said how inspired she had been by my message, and wanted to know what books I would recommend. She said their setbooks at school were Macbeth and To Kill a Mockingbird. My immediate thought was, why not Tell Freedom: Memories of Africa—? Why would Harper Lee be in vogue in South Africa and not Peter Abrahams?The Fees Must Fall movement called for a decolonised education, and I would argue that a decolonised literature is at the heart of it. And what better writing for such a project than that of Peter Abrahams?

My recent rereading of his The Coyaba Chronicles: Reflections on the Black Experience in the 20th Century has convinced me that Abrahams has an important place in a decolonised literary canon, and if we in South Africa do not understand how to reposition his work according to contemporary needs and tastes, then we need to look to the Jamaicans to show us how to do it.

- Elinor Sisulu is an author, literary activist and Editorial Advisory Panel member. Follow her on Twitter.

Thank you for this article. I am planning to register at Wits for doctoral studies in literary journalism and will be doing it on Peter Abrahams.

Perhaps we can talk sometime.