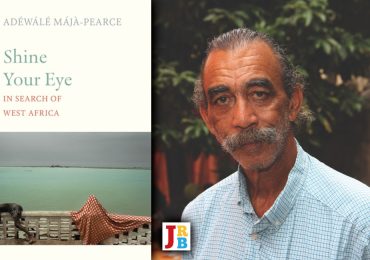

Header image: Binyavanga Wainaina (second from left) and Niq Mhlongo (far left), with American author and academic Jeffery Renard Allen, Lesego Lebo Ntuane and photographer Oscar Gutierrez in Maboneng.

Let me do the unthinkable by abandoning literature and the pen for a moment to talk about a few times I spent with the man I knew as The Binj—though it was literature that first brought us together, of course.

If I could link the late Binyavanga Wainaina to an important South African value, what comes to mind is our famous principle, ‘Batho Pele’—people first. For those who don’t know it, this principle is aligned to our constitution and requires public servants to be polite, open and transparent, in order to deliver good service to the public. This is the quality that struck me most forcibly about The Binj: he put people first. He was always surrounded by people; he was loud, fearless in confronting unjust systems head-on, always talking, passionate about African literature, helping young writers, teaching, learning—and chain-smoking. The Binj loved good beer, good company, and good food—three things we definitely had in common. I’m not surprised at all that, in his early days in Cape Town, he collected over 13,000 recipes from around Africa, or that he was an expert on traditional and modern African cuisine. That man loved good food.

I first met The Binj in Zanzibar, Tanzania in July 2005 at the Zanzibar International Film Festival. I was still relatively new in letters, then, with my debut novel Dog Eat Dog having been published just a year previously. I was recommended by him to the organisers of ZIFF after he had read my book, and this was my very first international appearance as an author.

I went to ZIFF with author Véronique Tadjo, who used to live in South Africa. We were asked to participate in the same (single) session, for $100 each. The session was structured in such a way that there were about twelve authors in one room. We came from Lusophone, Anglophone and Francophone countries, and we sat around the table talking about new writing in Africa. In this group of writers, I only knew Véronique, but it seemed she knew everyone. I remember being impressed by the man sitting opposite me, because he seemed to have in-depth knowledge about the continent, and when he talked everyone listened attentively. That man was The Binj. My immediate impression was that he was a very talkative, intelligent person who liked sharing his experiences with others. I didn’t know where he came from, but he made a lot of references to South Africa, Cape Town and the Eastern Cape—which helped draw me into the discussion during that one-and-a-half hour session.

After the session we were given a tour of Stone Town, where we were staying, which included visiting the Freddie Mercury House, learning about dhow construction and the importance of Mangrove wood, revisiting the slave and spice trades, and so on. I was surprised when the man I thought was from Cape Town asked the tour guide a few questions in Kiswahili and then interpreted back to us in English. In the afternoon The Binj, Véronique and I went shopping around Stone Town. Véronique chose my famous woolly ‘Rasta hat’ for me, and The Binj negotiated the price down, in Kiswahili, from $11 to $5.

In the evening The Binj invited us to Forodhani Gardens—a night food market near the beach. For the first time I was introduced to different kinds of African food. We walked to dozens of stalls, tasting fish skewers, octopus, mango slices dusted with salt, mishkaki and freshly-squeezed sugarcane juice with lime and ginger. As always, The Binj negotiated the prices in Kiswahili. From there, we went to the nearby Mercury Beach, where the festival had organised a storytelling session under a bonfire, complete with African drums. This is my 2005 Zanzibar memory of The Binj.

I met him again the following year in Kenya at Crater Lake. This time I was part of the ten-day Caine Prize for African Writing retreat, and it was here I wrote my short story, ‘Goliwood Drama’. Véronique was there, as a mentor, along with Jamal Mahjoub. The Binj came two nights before we left in a kind of motivational speaker’s role. He had won the Caine Prize in 2002, and established Kwani?, an important source of new writing from Africa, in 2003. At Crater Lake, everyone wanted to tap into his brain, to learn how to win the Caine Prize, which came with a lot of money and exposure. The Binj, Billy Kahora, Chris Mlalazi and I stayed in the pub until the early hours of the morning, drinking free alcohol and talking stories. The director of the Caine Prize then, Nick Elam, jokingly said to me and Chris the next day—’Don’t let Binya corrupt you. You’re here to write and not to drink alcohol!’ He had probably seen how high the bill was that morning.

In March 2008, The Binj and I met again—this time in Accra, Ghana, as part of the Pan-African Literary Forum festival. We were both facilitators: I was facilitating the fiction class (The Binj had recommended me to the festival’s founder and director, Jeffery Renard Allen), and The Binj the non-fiction class. We were with other writers from across the world, the South African entourage included Siphiwo Mahala, Sandile Ngidi, Zukiswa Wanner, Kea Modimoeng, Vonani Bila and the late Prof. Keorapetse Kgositsile, among others. We spent two weeks in Accra, and then a week in Kokrobite by the beach. At night we would visit a pub in Kokrobite and sing along to Bob Marley’s ‘Redemption Song’ and ‘Buffalo Soldier’, which The Binj loved.

In 2009 The Binj, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Chika Unigwe, Tolu Ogunlesi, Mama Ama Ata Aidoo, the late Chenjerai Hove, and indeed Niq Mhlongo were invited to a literary festival in Oslo, Norway. I remember one cold evening when Chika, The Binj, the late Hove, Chimamanda’s brothers Kene and Okey and I visited a pub, and had our loudest African corner. We were joined by curious Norwegian strangers who seemed to be fascinated by the fact that the late Hove took snuff. The Binj proposed a loud toast, of a different kind: he suggested that we pour a bit of snuff on the floor to thank our African ancestors, and instructed the late Hove to say something suitable in Shona.

In 2010, The Binj and I met again in Lagos, Nigeria. This time around, we were both invited to the Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop by Chimamanda. I remember our nights out at the Kuramo Beach and Fela Shrine, with Eghosa Imasuen, Onyeka Nwelue, Okey, and A Igoni Barrett. The Binj introduced me to spicy asun (goat meat) in Lagos.

In 2014, The Binj and I spent a week at Haverford College in Philadelphia in the United States. One night The Binj decided that we should visit some place near Haverford where the whole street is just pubs and breweries. The idea was to taste and learn about different beer-making processes. That cold night Ike Anya, The Binj, my sister Chika, Zachary Rosen and I hopped from one pub to another until the morning hours.

The last time I saw The Binj was in my hood, Soweto. It was 2017. He contacted me to say that he was around Joburg. His speech was impaired then, and he was no longer the highly spirited person I knew. He had suffered from successive strokes a year or two ago, and it was very difficult to follow when he talked. At that time he was in the process of buying a house in Yeoville, because he wanted to live in South Africa (for the second time). He mentioned how he loved South Africa because of our progressive constitution and our Bill of Rights, which protects the rights of the minorities. It was on a Sunday when I met him with Jeff Allen Renard in Maboneng. We had beer, and then I drove us to the Orlando Towers, where The Binj alone was brave enough to bungee jump.

After that I found myself travelling a lot, but The Binj and I stayed in touch. One of the things he wanted us to do when I came back was to attend an EFF rally, because he wanted to meet Julius Malema.

That was The Binj I knew: one of those rare breeds who could talk as beautifully as he wrote. He was conversant on every topic, as I learned. His curiosity was endless. I will miss The Binj, the hardworking writer who wrote most mornings and partied most nights. Open and approachable, he was committed to helping others in a most unselfish way. The Binj that shared ideas, drank beer, collected books, cuisines and friends. That Binj.

- Niq Mhlongo is the City Editor. Follow him on Twitter.

One thought on “[City Editor] The Binj outside books—Niq Mhlongo recounts adventures with his friend, Binyavanga Wainaina”