The JRB presents new narrative non-fiction by Pwaangulongii Dauod.

In December of 2014, barely one week after the department reluctantly approved my undergraduate thesis which, for varying reasons, had dragged past several deadlines, I embarked on a hesitant journey to visit my family, or what still remained of it, in the village of A—, in the hope that, somehow in the spirit of Yuletide, I would begin drawing to an end my desperate isolation of nearly a decade. The whole affair of leaving Zaria by bus on Christmas Eve for my hometown, east of the Niger-Benue Confluence, felt responsibly fair until I decided to get off the bus in Lokoja, still hours away from my destination. This precipitous disembarking was, again, not without uncertainty, due chiefly to the nervousness that consistently took possession of me every time I came this close to meeting my family, and was partly for the purpose of visiting the nearby relics of a mud house where my grandfather committed suicide in 1975; relics so haunting that I had developed a curiosity and began frequenting them, taking notes for my study and, subsequently, constructing for myself a narrative to comprehend the desolation that a year earlier had entered my awareness, by which I became vastly present in my own body, family, country and race—indeed, the Black Race. One day in the nineteen-thirties my grandfather, a young imam married to two wives and father of five children, decided to abandon his village, Holy Calling, and young family; he enlisted in the Royal West African Frontier Force, went to fight in World War II, came back from the Burmese forest and never returned to the person he was before the war. He lived in different places in the city of Jos between 1945 and the mid-nineteen-fifties, until he took up residence in a mud house in Lokoja, a city just three hours from his village of A—. The mud house was built sometime in 1958 and his suicide occurred in 1975. The house was eventually taken down in 2014.

On my disembarking in Lokoja that day, as the searing mid-morning drew firmer and firmer into a pitiless sun, the whole of my body began succumbing to the curious fatigue that usually beset me in that city. Without hesitation I slung my schoolboy rucksack over my shoulder and walked from the bus station towards the city centre, past the International Market, through dusty streets, and down the main road. Utterly fascinated by their stark nearness to the past that haunted me, I would usually make straight to several places of interest, such as the supposed Union Jack hosting site, the European Cemetery, the steel factory at Ajaokuta, the Samuel Ajayi Crowther Memorial Cathedral, The World War I Cenotaph, Lugard House, the Commissioners’ Quarters, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments of Colonial History. Instead I wandered through last-hour Christmas shoppers swarming around stalls, past people loitering around the stadium, and then all the way through several newly established estates. In the main square of one of these developments I decided to take a seat on a bench that had a good view. Even though I was seated in the open it seemed that I was floating in an airless contained space as I gazed at the view, as if some invisible cover had overtaken the city since the last time I was there. As I took in the structures around me—the houses, dusty streets, stalls, traffic and office buildings—once again it occurred to me how the open areas in places I had been wandering in northern Nigeria were being lost. These urban centres had about them a sprawling unimaginative bareness that filled me with horror, and this horror now seemed scarcely absent wherever I turned, television, the pages of books and newspapers. The urban centres’ self-evident lack of planning—no broad avenues anchored by art and architecture, no beautiful structures or intricate piece of engineering—displayed something deeper, something frighteningly shameful, a stark disregard for the human spirit or, as my friend Zachary once put it, a stiff-necked national anti-intellectualism. It was while thinking about this widespread artlessness that I stood up from the bench, taking advantage of the now subsiding sunshine, and walked through the city centre once more in the Christmas dust and took the road out of town.

I eventually arrived at the place where my grandfather, a world war veteran, had destroyed his own body decades ago. I must have stood there for three whole hours trying to make sense of it all, as I usually found myself doing when lost in such remote places, staring at the manner everything had become complex with time, overgrown plots, mounds of red earth, hay and rotted beams, shrubs, rocks, disused alloy, tall grass and rolling grassland. I wondered if beneath this geometry of destruction lay a more complex maze of shame, of fatigue. The noise of weavers in the canopies of nearby trees drew my attention and I raised my gaze. The tiny birds seemed to be scoffing at my repeated and futile visits to this place of destruction. It was probably due to the air, abundantly filled with a Christmas ambience and the suspicious sound of birds, and the shame shared by grandfather and I for isolating ourselves from the people who loved us, that I felt a deeply familiar horror, and I was not able to bear the place any more. I hastened back to town with images of human skeletons rattling in my head. I was lost. Despite being aware that my hometown was my final destination an intense disorientation took hold of me as I came back to town. I was indeed seeking a destination, a place not made with hands.

A young imam, so young and talented he was made chief imam of his village mosque at the age of twenty-two, abandoned his family and never returned home. Well, except for his charred remains after his 1975 self-immolation.

Later that day, having given up on continuing my homeward journey, I wandered through Lokoja town again until I arrived at the Niger River embankment where, in the falling darkness, I stood smoking and gazing down at fishermen setting off in their canoes onto the expanse of water. I cannot now recall precisely what I saw, besides the fishermen paddling downstream and their shirtless comrades gutting dinner catches on the shore, but it was so destructively hefty in the darkness descending over the place that I slowly collapsed onto the sands. The fatigue immobilised me for a long time; it took a while before my eyes could begin to make out things in the thin darkness around me. Gazing down the river, which lay darkly dreamingly vast before me, perhaps due to my earlier sighting of a man and his boy-apprentice distressingly pulling fishing nets from a canoe, I recalled the plot of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. In that brief moment I imagined myself the old man and the history of abandonment of family on my shoulders the marlin, and it was this wandering of mind as I looked at the water, I believe, which further prompted in me an absurd image of baby Moses drowning in the Nile hours before Pharaoh’s daughter considered taking her bath; believing that the fishers I earlier saw setting off from the riverbank for night catches had indeed gone further and further away, not to cast nets but to drown themselves at the downstream deep; accepting that the world was now one expansive river of darkness in which my forebears, having experienced destruction, beget me systems of drowning myself; recalling that during the past months I had been seeing young black African migrants on television, in the course of escaping destruction on the continent, drowned in the Sahara and Mediterranean seas. As the darkness drew even into the night I sat up on the sand. I felt hollow inside, yawning. I made to get back on my feet but the fatigue felt like metal. So I took to chain smoking and trying to remember my previous visits to this city, and began with recalling a long walk I had taken from this selfsame riverside early one evening to pay a hasty visit to my second cousin who had recently accepted a professorial position at the newly-established Lokoja university. The house, an apartment building that, though not as enormous and historical always evoked in me The House on the Embankment in Russia, was deserted and securely locked up. Uneasy, as though piles of broken bones were in my body, I went round the house in the hope of resting in his garden and found my second cousin standing atop the fire escape. I climbed up and rested against the railings, hesitating to ask why he was home but had locked the doors. I stood beside him, overlooking the corrugated roofs of buildings stretching onto the expanse of land reaching up and then along the river into the groves, where merchants under the auspices of the Royal Niger Company and then colonial Brits once lived and named the country as Nigeria. By way of explaining my regular visits to this city, I told my cousin how my recent happening upon an old essay called ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’ around the time I learned the story of my grandfather’s abandonment of his family and subsequent suicide had caused me vertiginous feelings and drawn me into coming back to scenes of such destruction, a nervous tracing of the past. On this Christmas Eve, however, as I sat alone by the river, gripped by fatigue and migraine and fear of drowning, I gazed at the darkness filling the face of the water in front of me and struggled to recall my cousin’s response to my observation that night atop his fire escape; I remembered nothing save the wildfire that appeared in raging plumes on distant hills across the river, which we both stood watching silently until daybreak.

I would later find myself telling my friend Zachary about this wildfire, that it was probably my recalling the seeming gulf in the wildfire, its solid blackness, and my own resolve to understand the wildfire as a phenomenon, one of the national (as well as continental) tragedies about which I had not only conceived a curiosity but had begun tracing that, after dragging myself from the riverside later that night, had me pacing my motel room and asking myself several questions I had been too deeply ashamed to ask. Zachary had underlined the paragraph where I described the above scenes and written beside it the words, abstract, too mannered. Even as I now compose this note I have no answers as to why I arrived at trying to understand ‘the national tragedies’ or any of the other questions, but the uncertainty of my footsteps in that room was evidence of the commitment I had given to understanding the centuries-old dismal circumstances that created my own nervous condition as a young black man in 2014, probably the same nervous condition that severed my grandfather from his beloveds. For the first time I felt the immediacy of the heritage of shame (in my family), the shame that partly contributed to my estrangement from my family, the shame that held back my grandfather from returning to his family after the war, the shame that made me feel burdened like an old man even though I was barely twenty-two years old that December.

My reluctance to continue my journey towards my family kept me in the motel. And as I paced my room, wandering in thoughts about the destruction of my grandfather and the ‘national tragedies’, many of which were equally visible here in Lokoja and in Zaria where I had journeyed from, I began to see that European colonisation was merely a fancy term for decades in which my ancestors were brutally infantilised. I saw that my grandfather was in the Royal West African Frontier to serve in a war for which he had no purpose, a war to which without the British Empire upon his land he would not have been attracted. I saw that my own father waited long and in vain for his life to change for good. He waited for good governance, and then for white people in the World Bank and Western metropolises to assist his country. I saw that during my last semester at university a professor could still confidently say to the class that Europe was responsible for the underdevelopment of Africa. I saw that my fatigue could be interpreted by the laces of these histories. Pacing that room, I thought hard about the reasons for the endless misery in my family, my tribe, my nation and continent, how it was possible after all for black people to be bought and sold. I thought about how it was possible that a certain Berlin Conference could ensure the destruction of my grandfather. I wondered, and how I now cringe at this, if there was any truth to the idea that Black Africans are inferior? Why did my ancestors fail to stop these foreigners? What was it about black people that made them fit for slavery and colonialism and such utter degradation? If truly my ancestors had great civilisations, steeped in science, art, society, medicine and technology, philosophy, why had the black race fallen behind the rest of the world? What preoccupied my ancestors during the centuries Europeans developed schemes in war, industry, exploration and trade? Is it not possible that those who, even today, teach us that Europe kept Africa backward, that the history of the backwardness of my race began with Europe, are not only trying to escape from reality but are also complicit in infantilising black Africa? Are they not deepening the inferiority of Africans and entrenching white, Western supremacy?

Bereft of any useful answers to these questions in that motel room, and incapable of stopping myself from asking them, I could not help but weep. And it was during this time I convinced myself to begin documenting the journeys that had created fatigue and disorientation in me and had resulted in my awakening to the age-old destruction that I feared would soon come upon my friend Zachary and me.

A Note on My Friend Zachary, His Darkness, His Destruction

And more than two years after pacing that motel room, on a day that began with Donald Trump giving a speech in Warsaw where he emphasised that Western ‘civilisation’ has been confronted by a more lethal threat with the recent migrations to the West than it has ever faced in the past, and that an urgent rallying together of Western peoples must happen to secure the occidental refinement of ‘symphonies’, ‘innovation’, the ‘fastest and greatest community’ known to mankind, I finished assembling the pages documenting the gradual awakening to wretchedness that underlay my wandering further and further away from family and friends.

I had begun this project in America in August 2016. Some months from late spring 2017, I locked myself inside my apartment, with an inexplicable urgency, and for weeks did nothing save composing the last pages of the book. After emerging from what felt like a dungeon, a desperate craving to return to reality took hold of me. I felt hollowly distant from the world, so I pulled myself through the streets to downtown Charlottesville, grabbed something to eat and, even though hefty fatigue had encamped in my joints, similar to that which usually plagued me when visiting relics of the past in Nigeria, I set off to wander the old city. I strolled through the university grounds, down gleaming, almost deserted streets. A profound foreignness that had not before occurred to me during the many months I had been in this place suddenly coated everything, the streets, the traffic lights, the buildings, sharply reminding me of my stranger status. Once more I began trying to make sense of the words I had heard Donald Trump utter, in light of the pages I had just concluded about the present-day condition of black people in the world. It was an ongoing season of nervous condition for me. Any words or images could trigger my thinking about being black. Even though I could not say precisely why, right in the middle of these thoughts I felt my eyes being taken over by a darkness. It felt unhealthily distinct from the night darkness and so rapidly staccato that I no longer could make out passing cars and other passersby. A short while later at midnight I was taken to the emergency room where I remained for several days in the mental ward.

My bed in the hospital was a foot from a wide window, so that even while laying on it I could still see cranes protruding against a multistoried building under construction. And a certain meaning sprung into view whenever I stood gazing out of the window. The skyline, the traffic lights, and distant freight trains seemed like images in motion on the thick pane before me, and this proximity to distance began playing with my mind. The gigantic building under construction, which I had been told by my nurse was an extension of the hospital, appeared so close to the sky. I began to suspect that the reason the mental facility was located up there on the uppermost floor of the hospital was to offer a subtle commentary about the suspended state of its patients, a fitting description of mental illness. We, the patients, were neither fully up nor on the ground, but stationed in the air. Even though there was a hard floor upon which the room, the bed and I stood, the impression of being suspended in air became deeper and deeper each day. Peering down at the street below, at cars coming in and out of the parking lot, the hesitant traffic meandering at intersections, the doctors in their uniforms expertly emerging from the chaos and making haste across the street into the hospital, the passersby along the curb, and the sudden distinctness by which all these movements impressed their forms upon my vision began to keep me at the windowsill. And indeed it was this floating about the ward, as it were, that made me restless, lying down and rising up, pulling the blinds up and down, seeking stability, weeping for hours on end. Standing at the window and watching the view with a wandering mind as I sipped at my tea early one evening, I saw a worker at the construction site with his body crooked on a crane, and I happened to recall that several months earlier I had walked the city of Charlottesville struggling to dispel from my head a distressing image of my dear friend Zachary. Despite being quarantined in a lunatic asylum in Nigeria, my friend kept mailing me handwritten letters. No month passed without a letter from him in my mailbox. It was Zachary, the scholar with whom I feel the greatest affinity, who heightened my own interest in studying.

My friendship with Zachary began in 2010. My girlfriend at the time, a friend of his, introduced me to him the November of that year. I was a teenager who had recently begun to read and write in English when I arrived in Zaria to begin study at Ahmadu Bello University. I was having great difficulty with the syntax of English. And this was a major obstacle at the time because it meant that to excel in my literary studies I also had to commit to a literacy programme. My girlfriend was compassionate, she knew of my problem and wanted to offer some help. She was the first person who saw in my desperate stuttering a struggle to express ideas about literature. She had coached me for the university’s preparatory exams and when I received the admission letter she wanted to put me in touch with an old friend of hers in Zaria. Someone, she said, who would help me become the reader of books that she had always imagined me to be. This someone was Zachary. My girlfriend was the first true other I had met in my life and in no time she became a bridge to my knowing of many others, such as Zachary, on campus. She was a Muslim, half Hausa and half Palestinian Arab; in 1984, she told me, her mother, a hopeless Palestinian teenager, had managed to find her way from the West Bank, through several North African countries, to northern Nigeria, where she married a Hausa man. My then girlfriend emerged from this marriage as an only child. Besides being the person who helped me discover love and trust, she gradually made me aware of the existence of the others, the plural, other worlds, which had been utterly foreign to me in the years prior. Before her my world was tiny, fearful, selfish, chaotic, and enclosed in brothels, nightclubs, drugs and fear. Besides using her own history to shatter every myth with which I had constructed my world, she bought me books. She had made me read numerous books before she would allow me to touch and kiss her. We visited all the street corners, markets and shops that sold secondhand books in Kaduna before I could touch her again, and it was this, her curious desire to keep me in the realm of words, letters and the pages of books, that made her visit the campus and introduce me to Zachary, on 19 November, 2010.

And our own friendship began with Zachary walking me every other day to find the realms inhabited by the others on campus: the budding intellectuals, singers, poets, scientists, writers, painters, dramatists, designers. In no time my world was awakened and expanded by a stunning warmth. I saw teenagers like me in complete freedom, at readings organised by the Creative Writers’ Club, at the Friday night Cipher and Poetry Slam in the university Sculpture Garden, and the community began to build a strange nameless fire in me. For the first time in my life I was in the midst of people whose immediate needs were not food, money and the politics of ‘vote and be voted for’. As the fellowship deepened, it occurred to me that most of these young men and women faced a similar anxiety, they were boys and girls who, like my grandfather, were fleeing from home. They were especially at loggerheads with their fathers. On campus, in the company of Zachary, I started to care less and less for the worlds that existed back in the neighbourhoods. For Zachary, C Boy, and every young intellectual I befriended, the dream was to realise Zaria as an intellectuals’ hub, a place of original thinking and indigenous breakthroughs in technology, culture, science and economics. Like The Frankfurt School or Howard University’s social scientists of the nineteen-thirties, they wanted to create The Zaria School. Zaria would grow to possess power and attention like Paris, London, Berlin, New York. Let us stay and be intellectuals here, said Zachary once during an Intellectual Discourse session at the Creative Writers’ Club. Abroad, he continued, amidst white people, we can access more respect and money, but we should stay home and grow this place. We should not be ashamed to be fulfilled as intellectuals at home, said C Boy later that evening, in his off-campus apartment. I was astounded by the single-mindedness displayed by these folks. They were just three, four, five and seven years older than me but I found a genuine conviction in their eyes that I had not seen elsewhere. Before this time all the writers, philosophers, journalists, scientists and artists I had read—both African and non-African— lived and created from Western metropolises. In my head these creators and thinkers were as powerful as the cities that they lived in, but gradually I began to doubt if the power they held in my head came from the cities or from their imagination. Little by little I felt something strangely compelling whenever I heard Zachary and C Boy speak about power and Zaria. I felt a loosening of my own imagination. I actually began seeing the possibility of an International Zaria. I would rove the campus at night and catch myself wondering whether the passion of my friends could translate to reality; if Zaria, like London and New York, could pull powerful publishing houses, financial institutions, theaters, open spaces, and academic authorities to its streets, if Zaria could become a home to lectures, festivals and international curiosity.

After Zachary had established me within these realms he decided to help me see the world in his own life and in books. He had begun assisting me to understand the syntax of English. His Michel de Montaigne collection introduced me to a whole new sensibility, the essay form. His obsession with Werner Herzog, whose The White Diamond and Lessons of Darkness he considered ‘purely endless’, came gradually to steady my own gaze when it came to narratives and, subsequently, the world. My friend is now only in his thirties but his inclinations are utterly old-fashioned. He does not print his letters. He uses neither a phone nor the internet; he is taciturn and travelling on foot is one of his major principles. His eyes, which I loved being cast on me, contain a childlike innocence. He wanted to be a philosopher, or a scientist, and despite the innocence one could see fierce conviction in his eyes. All the years he spent in Zaria, where, like myself, he was a student, Zachary never spent a night sleeping; his off-campus apartment, or the Library of Congress as his associates named it, was filled with obsolete lab apparatus, documentary films on obscure subjects and an unimaginable collection of books, most of which dated back several centuries. He possessed a strange, inexplicable relationship with darkness and had since his second year committed to some obscure scientific enquiry into it. Occasionally he wandered at night with his stills camera, down campus, far into Old Zaria City, through inner streets and alleyways and mosques, settlements that perpetually lay dark without electricity, and then at dawn he would stroll back home with photographs of images made indistinguishable by blurry swaths or utter blackness.

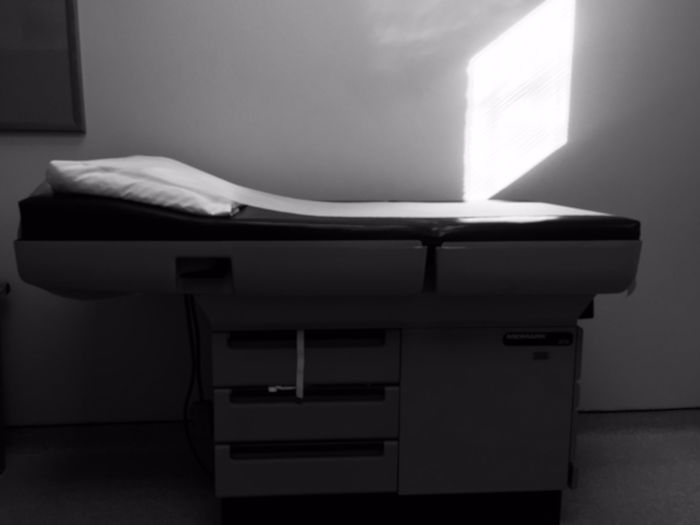

I was barely taken aback when he confided in me that the subject of his long study was, in fact, to determine the geometry of darkness. But it was as ambiguous to me then as it is now. Upon entering his dim, musty room, which also was notably studded with varied apparatuses such as measuring tapes, wall clocks, thermometers, speedometers, rulers and abacuses of several types, Zachary was always to be seen hunched over books and papers at his desk, facing a corner of the wall as if the subject of his study extended inside the bricks. He slept on the floor but had purchased a scrapped and reconditioned hospital bed and had it positioned by the only bare wall in the room. He initially did not reveal the purpose of this bed in his affair with darkness. But one day, as the afternoon was drawing to a close, I walked into the room and found my friend photographing the bed, as the sun coming from a small window cast a beam of light in the shape of slanted square. He told me that he was taking the photograph to aid his analysis of the anatomy of darkness. He and C Boy had begun composing a treatise vaguely titled of darkness.

It was customary for him to stay locked in his room, drinking and reheating coffee, reading and scribbling notes. Only on Wednesdays would he emerge, with eyes that were taken over by vast uncertainty or fatigue, as the case may be, to visit the gym where he trained in the sport of boxing.

Yet Zachary’s fine and intimidating intelligence did not save him from receiving the poorest grades in his class. He attended his classes, studied in his room and all the libraries nearby in Zaria, procured books with the allowance that came monthly from his older sister, but the moment it was time for an examination, melancholia would take possession of him. He would become compulsively irritated and take to violence at the slightest provocation. By this time I was beginning to be affected by the uncertainty surrounding his mind. I was convinced that a strange disease, probably the same as my grandfather’s, had begun eating deep into my friend. It defied all logic that he had so many books and breathless insights—he even lent books to professors and some of us his younger friends—but chronically got bad grades.

It was during this time of desolate floating between incomparable knowledge and terrible academic performance that Zachary offered to take me on a walk one night to talk about Thomas Carlyle’s ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’, which, for several reasons, had obsessed me since I happened upon it in the university main library. Carlyle’s note, published in 1949, was merely a racist composition about freedom and the economy of black slaves in the West Indies. However, I could not help reading it over and over; it had a character that deeply struck me, a character that frighteningly resembled something from my childhood. When I was a child my father was obsessed with talking about the question of his growing up fatherless. Any slight provocation was enough for him to launch into a lecture on how privileged we were as children with a father in the home. He organised monthly family meetings and his favourite word when addressing his wives and many children was ‘question’—the Food Question, the Question of Respecting his Fatherly Presence, the Farming Season Question, the Question of Division of Labour, the Question of ‘My’ Truck, the Question of School Uniforms. He described the family’s headaches as a sort of question. He possessed a single-mindedness and deep authority over the family during the meetings whenever he spoke about these questions. Not only did I accept that he was ‘the owner’ of our family, but I was also convinced that the family was irredeemable, in terms of those questions. I was a child then but I could see and feel these things. My father raised these questions as if he himself was not a member of the family, but a powerful envoy on a mission to address it. Even as an adult now, whenever I come across the word question I am reminded of my own family. So even though I had read a number of racist documents prior, Carlyle’s short essay was the first composition in which I encountered the deep single-mindedness of a white man regarding the question of people of my own race. More than anything else, I was preoccupied with the title, ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’. Incidentally, I was not offended by the essay itself, because I already knew that white people spoke about black people in such a manner at the time of its publication. But rather, it began to feel as if I was being summoned; I began to wonder if it was necessary for me to initiate another Discourse on the Negro Question in this century. I started having the urge to make everyone around me, including Zachary, see that we were ‘Negroes’, Negroes still surrounded by centuries-old questions. I would wander through the Zaria campus and imagine myself having been given a responsibility by Carlyle’s racist text. Just as my father’s words helped defamiliarise the miseries in my family by tagging us as a question for constant discourse, happening upon Carlyle’s piece indirectly summoned me to recognise that there is still a Negro Question in the world today. And I immediately wanted nothing then but to start my own assessment of this Question. And this is what preoccupied my mind for many months at the university in Zaria, which my friend Zachary had seen and hoped to explain to me.

However, rather than give his intended exposition on the essay as he and I walked through the campus, Zachary started on his characteristic analysis of layers of darkness. He strayed and could not make any meaningful observations about Carlyle’s essay. He went on and on talking about discoveries in his own study of layers of darkness. His scientific (mathematical) insights into darkness were not only beyond my comprehension then and now but also were clearly symptomatic of the utter blackness in which he was desperately drowning. If my friend were a Westerner or a resident in the West, perhaps a young European or American, he might have been hailed as an emerging philosopher of his generation. But this was not possible for him as a black man in a black world, a man born in a place notoriously disdainful of his kind of imagination and inquisition, a place with no regard for true human curiosity. His philosophical talent and inclination were too sharp, too earnest, and were agonisingly unrecognised. It was this long-felt obliviousness of the entire world to his imagination, which, I strongly believe, became the evil fire that caused the rapid deterioration of my friend. His is a unique case in all the destructions I have so far witnessed. Zachary himself had foreseen his own tragedy when he argued that his scientific study of darkness was to pierce the geometry of known things to reach the very soul of existence, where, he further observed, we could find the realm of true but unanchored meanings. I cannot now piece together all the observations he made that night as we wandered on through the streets in Zaria; however, as we made to take leave of each other, he first counselled that I desist from trying to understand the so-called ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’, an essay published by a European, and expressed his absolute optimism about the same Question. He has never stopped being an optimist. Despite the disrespect he receives from the world and his countrymen he refuses to despise.

Years later, as I began composing these pages, it occurred to me that his refusal to speak about Carlyle’s essay as well as the present-day ‘Negro Question’ in the world was either because he himself, whatever his knowledge of science and history, was not aware of the connection between our lives and the thread of dismal history from which our generation was born; or his silence came from the certain shame that he himself had once described as burdened upon us by our reckless ancestors; or he had been seized by fatigue occasioned by the very Question. But right then, though I was naïve, I knew that both he and I were young black Africans who credibly belonged to a ‘Question’ in this century.

Months after that awkward evening wandering through the neighbourhood, Zachary graduated, after nine years of pursuing a four-year degree, and of course with the worst grades. Before leaving Zaria he discreetly gathered up all his books and drowned them in the river. This was the destruction of my friend. Nothing prepared us for this phase of his life. He had only become more withdrawn, taking to a curious silence during the months leading up to his drowning of his research and intellectual life. My friend had stayed within a system thinking that salvation would emerge from the pages of books, but the darkness around him was bigger than enlightenment. His books were his life; drowning them in the river marked his surrender to the heritage of destruction. After this he went back to his family in Abuja and, as he wrote in his letters, his interminable animosity with his father became much fiercer. A while later he eventually lost it and had to be quarantined in a mental home, from where he consistently wrote letters on foolscap and mailed them to me in America.

So it was from the above memories of Zachary that a particular one began haunting me by the time I moved to America. The image, the very crooked one I happened to recall by the windowsill of my hospital room, tormented me as I wandered every day in Virginia, which, memorably, also has an unspeakable history of not only disdaining black bodies but also prospering by destroying them. And indeed if today there is anything still more nervous about the Black Race besides a massive, stale Third-Worldness, it has to be this: the black body does not only shockingly exist in profound dishonour but it is also being overwhelmed by severe fatigue anywhere it finds itself, in Europe, in the Americas, Asia, Australia and of course, nauseatingly, in Africa. It was my awakening to this fact of the Black Race in 2012, the year I became twenty, which filled me with fear, and this was perhaps why in 2014, after a prolonged witnessing of destruction around me, especially as realised in people like Zachary and my grandfather, that, little by little, I became convinced of my own imminent extermination as a young man.

Even though my recollections of Zachary obsessed me over the years, there was one particular moment that upset me deeply and kept me aware of the dungeon where I myself belong; the dungeon that made it impossible to be able to compose these pages in Nigeria, on the African continent; the dungeon that ensures that to be human I have to sojourn through institutions in the West, begging for a degree, subsidy and endorsement; the dungeon that keeps my body homeless, placeless and humiliatingly nervous anywhere it finds itself in this world while people of our ages of different races live in comfort on their home turf. In this image of my friend he was bare-chested and crooked over the table in his studio, working on a dismantled computer in the shine of a hanging oil lamp. It was late at night and I was visiting. His face, bearing giant spectacles, was pulled close to the table. Though there was a slight beauty in the way his dreadlocks, remarkably long and hefty and ungroomed, spread onto the bits of hardware scattered across that table and shone under the huge lamp above his head, it was the manner in which his trunk tensed up in that unbalanced, brittle posture that lingered with me. It was vulgar to allow this crooked image to stay so long in my mind but it has become an image of enormous significance. I do not embellish this. Zachary does not consider himself a victim of an unjust Nigeria, or the British colonial fraudsters whose dream it was. I do not intend to establish his victimhood either. I do not define him by such jaded postcolonial language. I recall asking him to put aside the repairs he had been doing since daybreak was at hand, but he was stubborn and refused. I watched him labour in the heat and dimness, afraid to leave him, wary of stepping into the darkness outside; neither of us at the time knew the hour at which this world would disappear to us. The world has practised a long tradition of exterminating young black people like us, and our comrades in Zaria, such as C Boy, Terry, Abdul, had begun disappearing. Except by political and social privilege, no one can actually outgrow this tradition.

I do not associate this recurrent crooked image of Zachary in my mind with the series of letters—treatises on water, night-time light, Wu-Tang Clan, sex, destruction; incomplete observations on photographs; ramblings on my obsession with the Negro Question—he has been sending me from his mental home in Nigeria for the past years and to which, guiltily, I have not written a good response. I attribute its continuous stay in my head to the anxieties inside me that made it possible for such an image to affect the way I now see the world. I put it to the brutal conditions that adeptly placed Zachary into a narrative, a nation in which no one regards his body and imagination. I also accuse the innumerable forces that seek to normalise this truly absurd position, the forces that now believe that the centuries-old negro question of misery, underdevelopment and continuous destruction, phenomena which claimed my grandfather and to which Zachary and I still belong effectively, has become jaded and thus can be discarded. I also blame it on our forebears, the men and women whose action or inaction created this nervous condition for my generation. I am indeed reluctant to show them any respect. I sympathise with my grandfather, my father and all the ancestors who were destroyed by the weight of European inhumanity but, honestly, I cannot say I have useful regard for them. My refusal to feel any sense of pride in my own ancestors is part of the heritage of shame that destroyed my grandfather and subsequently destroyed my own family. I am aware that some resisted and fought back against Europe and her machinery. I am aware that some of these ancestors died by suicide in order to preserve their dignity. I am aware of strong black men and women who fought to the death in order to repel colonialism and slavery. But also I know that what happened to my ancestors was not a single night affair. It was an enterprise lasting hundreds of years, a business that began with gunpowder, religion and explorers; and this business would later set up consuls, offices, straits, railroads and ships mainly to plunder land and bodies. The great emphasis of this long night of indescribable cruelty has always been about black bodies, the helplessness of victims in shackles, in labour fields, on ships in transit, mutilated bodies. They are, indeed, the true conditions of past eras, and in many ways conditions of this present time. History books, professors and the university campus in Zaria taught and exposed me to the humiliation that my ancestors suffered. However, my curiosity has always drawn me to wonder why it all happened. And this curiosity is now as vertiginous as the fatigue in my body.

I actually did not notice the crooked photo of my friend Zachary at the time I sat two chairs away from him in that room more than three years ago; however, as I set off assembling my notes, walking Charlottesville every day, from the amusements downtown to the breathtaking scenery of hills, railroads, woods, libraries, theatres, bookstores, the Monticello, roving the arcades of imposing buildings in the disturbing quietness of the almost deserted campus at night; befriending young scholars with great thinking and originality, contemplating how ‘we’ came to be distantly lagging behind the prosperities of the world, wanting to know my thoughts on the ‘position of the black body and what the world has made of it’, by which I mean to affirm or denounce the inconveniences (or fatigue) passed on to me by my forebears, it began to occur to me while I gazed upon this position of Zachary in my mind that his posture over the table, shone upon by the hanging lamp, held some significant meaning. I am lost, ill, and susceptible to reading too much into situations, but not this. I observed that his crookedness at the table notably obscured his waist. This crooked position made the trunk of his body, which bore more of the light, display his tense black complexion, so that he appeared in that room as if the strength of his body had all streamed down into his skin colour, giving a brittle impression. Picking up and dropping the tools at the table, his sweating became profuse from the dark of his body in a way I had never seen, and in that long moment of exertion it seemed like I was staring at a trunk that been smothered by a dark, wet living sheet. In that moment it appeared as if every movement by Zachary only pronounced the strange discomfort of his young black body. I felt fear once I saw it years later. And it is as I now recall also, in fact, that I could see that the intensity I beheld years ago and which had returned times without number to humiliate me is in no way a unique phenomenon, but a fitting commentary of the nervously homeless position of the world’s black population both as natives on the continent of Africa and in the diaspora.

Unbeknownst to me, it was as if the world bullied me all my life into staring and taking in the realisation that all the women and men, boys and girls, individuals through whom I became aware of myself, possess the same nervous posture as Zachary. Thus my own individual fatigue also finds its meaning in this nervous posture.

This posture is a posture of destruction, and the world that centuries ago began its enterprise of destroying the bodies of people like Zachary and my grandfather has not broken off from its own denial. The world will say the darkness and destruction of which I speak are nothing new, that the case has long been made, that it has now become a heritage of ‘racial paranoia’. But it is this heritage of destruction and underdevelopment that first began emerging in my awareness in 2012, and which eventually caused me to break down time and again as a twenty-two year old in 2014, that I seek to narrate, even through my scarcely sensible fatigue.

- Pwaangulongii Dauod is the former creative director at Ilmihouse, an art house in Kaduna, Nigeria, and is a 2016 MacDowell Colony fellow. He is currently working on two books, a collection of essays, Africa’s Future Has No Space for Stupid Black Men, and a story collection, The Uses of Unhappiness. He was shortlisted for the 2014 Short Story Day Africa Prize, and was awarded the 2018 Gerard Kraak Prize. He holds a MFA from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. His writing has appeared and is forthcoming in Granta, Callaloo, the Evergreen Review, the Literary Review and Brittle Paper. The title essay of his forthcoming book, ‘Africa’s Future Has No Space for Stupid Black Men’, has been staged and performed in Nairobi, Zaria, Abuja, London, New York, Berlin and Rio de Janeiro.