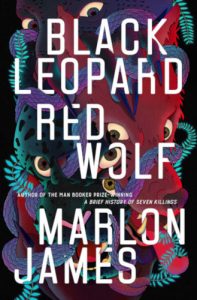

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is a frustrating could’ve, would’ve, should’ve affair, although it may yet prove to be the beginning of something, writes Tymon Smith.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf

Marlon James

Hamish Hamilton, 2019

In my personal, once vivacious, now sadly less regular reading life, there are two books that mark either end of the imaginary shelf of my interests, from the beginning of the twenty-first century to 2015. On one end stands Don DeLillo’s 1997 epic magnum opus Underworld, a novel described by Michael Ondaatje as ‘an aria and a wolf whistle’ to the turbulent, late-Cold War uncertainties of the second half of the twentieth century. On the other stands Marlon James’s 2015 Man Booker Prize-winning A Brief History of Seven Killings—a bass-heavy, reggae-charged, ‘five-o’ cornerboy shout-out to an alternative history of the same century.

Seven Killings is a periphery-focused, Joyce-infused, time-and-space-travelling, difficult, overly ambitious but ultimately brilliant literary moonwalk between the boundaries separating historical fact and its unique, witty, powerfully questioning reconfiguration of the events surrounding the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in 1976 and their aftermath. Both books provide unexpected, time- and thought-consuming templates for how to navigate the difficult and increasingly newspeak-infested divergence between the black and white, right and wrong certainties of the map of the world and the ever-shifting, fluid realities of life on the ground. DeLillo took the simple object of a ball, the object at the heart of a seminal fixture of ‘America’s favourite pastime’, and used it to track the shift from the us-and-them, commies-vs-freedom-lovers platitudes of the nineteen-fifties to the nuclear-waste-dump, second-thought-too-late regrets of the decade following the smashing of the Berlin Wall. James took a gun and the men who had used it to paint a different kind of picture of a not too dissimilar period, when gang violence, bolstered by Cold War politics, swept the streets of Kingston, Jamaica and caught the island’s most famous son in the crossfire, before Rastafarian vengeance took care of those who had tried to kill him.

All of which is a perhaps long-winded and very roundabout way of saying that for a once enthusiastic, now horribly lapsed reader, whose tastes are defined by two ambitious, sprawling, novels characterised by toe-dipping into History (capital H), the news of James’s new book presented something of a perplexing quandary. On the one hand, the question had to be asked as to how James would follow up the success of his over-vaulting, dazzling third novel. On the other was the announcement that rather than continuing with the historical-and-then-some explorations of his first three books, James would be writing the first of a trilogy of fantasy novels that he described in a throwaway comment as an ‘African Game of Thrones’, a tag that has stuck. So, after five years there would be a new Marlon James book, but as at best an occasional fantasy reader, would I really read it? Of course I would—after all this is Marlon James, and in the era of Wakanda, the award winning Broken Earth trilogy by NK Jemisin, Afropunk and of course the rise of Afrofuturism in every cultural sphere from literature to fashion to Beyonce’s music videos, the first instalment in the Dark Star trilogy seemed tantalisingly immediate and intriguing.

In the month between the book’s release in the United States and its appearance on local shelves, the Western hype-machine has been working overtime to promote Black Leopard, Red Wolf. It began with a galley blurb from Neil Gaiman comparing it to Tolkien and Angela Carter, followed by an expansive profile in The New Yorker, a glowing review by the feared Michiko Kakutani in the New York Times, Vanity Fair and GQ interviews—all of the things a Man Booker Prize winner should be entitled to. However, as the Fugees warned us in the nineteen-nineties, sometimes it’s best that you don’t believe the hype. For, in spite of its undeniable depth of research, its refocusing of the precolonial narrative on a richly-imagined, self-sustaining, mythically-infused African tale, in which the supernatural and the real coexist and which is full of beguilingly-realised characters, Black Leopard, Red Wolf suffers a little too much from the pressures imposed on it by its author’s perhaps grandiose intentions. It is a book written by a great writer who wants to be everything to everyone, and it suffers because it has forgotten to focus clearly on itself.

James has said that the trick of his trilogy, which is set in precolonial times yet told squarely through a present-day Afrofuturist lens, is that each novel will relate the same series of events from the perspective of a different character, a conceit inspired by a discussion about the television series The Affair. This Rashomon approach may yet prove to be more than just a clever device and tie the three novels together in a mammoth epic that is more than the sum of its parts—after all, the third instalment of The Lord of the Rings films won the Oscars for all of them. For now, though, the Dark Star trilogy must be judged on its first instalment as it exists on paper, independent of the hype and the pressures attendant on the writer of an acclaimed, award-winning book that readers like me regard as the great literary achievement of the early years of the twenty-first century.

The hero of this first book is known only as Tracker: thanks to a preternatural sense of smell, tracking is what he does best. When the story begins Tracker is being interrogated by a murky figure known as the Inquisitor. He tells him, and us, ‘The child is dead’. As the rest of the novel will show, James has thus set up early on that while the story, in true Tolkien fashion, will involve a quest, the quest itself is the material and not the outcome—which has been revealed in the first sentence. Tracker begins with a long back story about his terrible family life, his olfactory powers and his development as a loner, cynical and tied to no one, sexually other. He is brought by circumstance into the ambit of a shape-shifting half human, half leopard fighter, and charged with the protection of a group of outsider children with supernatural powers who live in the care of an ‘anti-witch’ called the Sangoma. The first part ends with the destruction of the children’s sanctuary and the dispersal of the Sangoma’s charges. They and perhaps the Leopard will remain the only things other than himself that Tracker really cares about.

The world of the story is one of different kingdoms, warring tribes, and supernatural forces that are part and parcel of everyday life, and it is violent and highly sexualised. At first James’s particular penchant and talent for operatic descriptions of violence and his evocation of the world of the story, with its many elements derived from various sources of African and diasporic mythology, is refreshing for its inventiveness, its strangeness and its dedication to the mission of bringing genre fantasy into a reasonably new arena of exploration. It is intriguing to see James’s very active imagination laying the groundwork for what will follow—stumbling sometimes, particularly when it comes to dialogue (often overly expository and predictably biblical) but gradually painting a picture that is full of action and occasional dark humour, in the vein of an Anansi tale or even the multi-universe stories of comic books.

In the second part, Tracker and the Leopard are reunited in a mercenary mission to find a child, together with a band of similarly ruthless and specially-skilled characters, for a slaver whose interest in this unnamed child is unclear—but hell, he’s paying, so off we go. It’s here that things begin to fall apart, mainly perhaps because James falls back on his talent for descriptions of violence and sex at the expense of the narrative, which, even though we know its outcome, still needs to be clear and interesting enough to hold the attention of readers expected to stick out the novel’s six-hundred-plus pages. Unfortunately, while there are several strong portraits of new places and characters, the book suffers from James’s determination to use his writing as a platform for addressing issues rather than allowing these concerns to arise naturally from within the story and through the characters.

The violent scenes all eventually tumble into a fog of battles, fights, weaponry and ruptured anatomy that serves little purpose other than extending the length of the manuscript. The journey is not engaging enough and, frankly, Tracker as a main character is pretty flat and one-dimensional, and hanging ideas about Africa’s precolonial grandeur, alongside liberal-minded attitudes to gender and sex, is not enough to make him interesting. James’s skill for dialogue, dialect and interior monologue, which served him so well in A Brief History, lets him down monumentally here, perhaps because in this book it is derived not from experience but from an idea of how people might talk in a world in which we could never have heard them. Thus we end up with the kind of clunky, unwieldy, and portentous-with-ambiguous-foreboding kind of thing that’s been a staple of fantasy books for decades.

It has its moments, but as a whole Black Leopard, Red Wolf is disappointing not only because of who its author is and what he achieved on his last outing, but because in spite of its worthy intentions, aspirations and recognition of the times in which it is written, it fails on so many basic levels. Its intentions are writ large, but like Tracker they tend to beat the rest of the book into submission.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf may well yet work as the foreseen television adaptation it is set to become under the stewardship of Black Panther star Michael B Jordan, but on the page it is bombastic, inflated and lacking in any real depth of feeling. As a follow-up to one of the century’s most difficult but rewarding books this is a disappointing mish-mash, a regurgitation of familiar tropes in a different setting, which panders to the knee-jerk woke revisionism that tends to drown out constructive reevaluations of genre and its limitations.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is a frustrating could’ve, would’ve, should’ve affair that may yet prove to be the beginning of something I can’t quite see—but at the moment is something I am about to quite easily forget.

I was wondering if you could help me I am trying to contact Tymon Smith on behalf of the English Academy of Southern Africa. Could you please send me his contact details or forward my details on to him. He has given an award by the society and I would like to know if he would like to accept it.

I am the admin assistant for the society.

Kind regards

Karin Basel