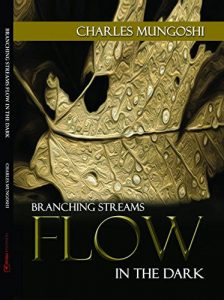

Literary giant Charles Mungoshi died on 16 February 2019, at the age of seventy-one.

Mungoshi was born in 1947 in Chivhu, Zimbabwe, and is regarded of one of that country’s foremost writers. He wrote in Shona and English, and won the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Africa region) twice, for his short story collections The Setting Sun and the Rolling World (1987) and Walking Still (1997). Two of his novels, one in English, Waiting for the Rain, and one in Shona, Ndiko kupindana kwa mazuva, both published in 1975, received International PEN awards.

Mungoshi was born in 1947 in Chivhu, Zimbabwe, and is regarded of one of that country’s foremost writers. He wrote in Shona and English, and won the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Africa region) twice, for his short story collections The Setting Sun and the Rolling World (1987) and Walking Still (1997). Two of his novels, one in English, Waiting for the Rain, and one in Shona, Ndiko kupindana kwa mazuva, both published in 1975, received International PEN awards.

To commemorate his passing, The JRB is pleased to republish an interview between Mungoshi and Lizzy Attree, excerpted from Blood on the Page: Interviews with African Authors writing about HIV/Aids. The interview took place on 7 August 2006, in Harare.

Attree writes:

Charles Mungoshi’s interview places him in the centre of a much neglected storytelling tradition from Zimbabwe, which features HIV/Aids alongside all the troubles and tribulations of life he has written about so beautifully since the nineteen-seventies. The interview attempts to focus on the short stories ‘Did You Have to Go that Far?’ in Walking Still (Baobab Books, 1997), and ‘Letter to a Friend’ in Seventh Street Alchemy—a selection of writings from the Caine Prize for African Writing 2004 (Jacana Media, 2005), but embraces much else, including Sufism, music, quantum physics and the writing process itself. It was a real pleasure speaking to one of Zimbabwe’s most respected writers.

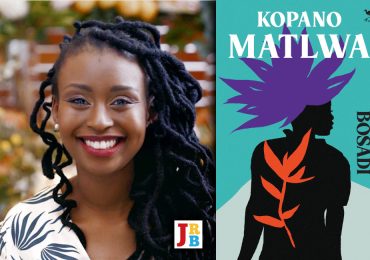

Branching Streams Flow in the Dark

Charles Mungoshi

Mungoshi Press, 2016

Read the interview:

Lizzy Attree: It says in the beginning of this book [Walking Still] that you published some of these stories in Horizon magazine in a different and shorter form: do you know how long before they were published it was that you wrote these stories?

Charles Mungoshi: I think some of these stories were maybe two years in Horizon first and then I collected them, I had nothing to do, but I collected them in my mind and could expand this and see some possibilities in these. It could be two years before the stories were published together.

Lizzy Attree: And just before I ask you about the main story that I’ve been focusing on, ‘The Wedding Singer’ is the story just before that, and it’s the woman in the story who is commentating on the lies …

Charles Mungoshi: That’s a long gestation, it’s the elephant eating thorns. Ya [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: Because that one’s very powerful.

Charles Mungoshi: You think so? Maybe in terms of crafting, but in fact, that’s how I put it, but that happens. I thought from her point of view, being who I am, sometimes we think for the women, which could be wrong, women don’t think that way but I thought she would think that way.

Lizzy Attree: One of the things that is most powerful in the whole collection is the way you relate the perspective of women …

Charles Mungoshi: You make me very happy, on a sad day [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: Is it really sad?

Charles Mungoshi: The lights are out [referring to the constant power cuts]. What are we talking about? Survival [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: Pretend it’s not happening. I wanted to ask you specifically about what she is thinking about, it’s the death of the child that she is carrying isn’t it?

Charles Mungoshi: No, she’s worried about …

Lizzy Attree: Is she going to physically abort it?

Charles Mungoshi: She’s not going to abort it. How did you read it? She won’t see it, the woman who took her man. What’s here will survive, because that’s his child, and you took my man, I’m going to kill you for taking my man.

Lizzy Attree: I wondered whether if it was meant to resonate with Aids, so it’s not because of a disease?

Charles Mungoshi: No, no, no, it’s simply straightforward, why did you have to do that? No, she wants to kill the woman. But I don’t know whether she will get the man, because the man used her. She was just a housemaid or something like that.

Lizzy Attree: And the bride is not innocent either.

Charles Mungoshi: She’s a schoolteacher or something like that—does that worry you?

Lizzy Attree: No. The man has been unfaithful, but they’ve both lied, coming to this marriage, they’re both concealing what they are. You talk about the shadows and the darkness, is that the lies?

Charles Mungoshi: Of course. There we go. I always like criticism because it brings out the light in my darkness. It makes the world go round.

Lizzy Attree: So the main focus of the interview is the story ‘Did You Have To Go That Far?’

Charles Mungoshi: Is that a Horizon story again?

Lizzy Attree: A lot of the stories were published before, but was this one?

Charles Mungoshi: Originally? I think that’s one of the originals in the book.

Lizzy Attree: It was first published in this collection, Walking Still?

Charles Mungoshi: Ya, but it was worked through and through, I thought I’d given it to somebody, I couldn’t do it in other words, until when I sat down and it wrote itself.

Lizzy Attree: Because it’s the one I’m focusing on, it’s also interesting that it’s the longest one in the collection.

Charles Mungoshi: It could have developed itself into a novella or even a novel. If I’d paid attention to all the characters, but there it is.

Lizzy Attree: It’s very careful about changing the perspectives and playing with events in a child’s life, the way Damba observes his friend and his parents, it very cleverly shows the development of his understanding, using the child’s perspective, of whose fault certain things are.

Charles Mungoshi: Is he growing up? [Laughs] Rites of passages can be like that.

Lizzy Attree: For sure. It’s symbolic of a lot of your other stories which focus on an absent father or a missing male role model in each of the families; or where there’s a male role model he’s often manipulated by the women around him. Whether knowingly or not, did you consciously chose to include Aids as a subject for the story?

Charles Mungoshi: No, Aids was a passing thing, I wasn’t dealing with Aids, I was dealing with people and how they live.

Lizzy Attree: And particularly the way things like Aids become …

Charles Mungoshi: The whole thing, because we are Roman Catholic, because we are Irish, how it affects us and how it changes things and how a man-less woman lives next door, how it affects a community, that kind of thing.

Lizzy Attree: And people’s assumptions that she’s a witch …

Charles Mungoshi: There is no hard and fast rule, there is no philosophy there. It’s simply the philosophy of living, survival, what are we doing? And Aids, ah, ah, ah, ah, no, we don’t touch that. That’s how it is. Oh, Black, no don’t touch that. Jew! Ah, ah, ah, it says Hitler, that kind of thing.

Lizzy Attree: So you’d connect it with that kind of religious discourse, that tells people who is good and bad, or does it come from a more local understanding?

Charles Mungoshi: Our life has been sort of live and let live, so if I go to kill an animal, I eat it and the vultures finish whatever’s left. Feel good with what you have. Amass a lot of strengths, whether intellectual, material, sexual or whatever, I think, actually, sexually a lot of women, a lot of children, if someone wants to fight me, my children will fight, and also the women, I get rich, they want to be fed. There’s a personal, practical example of someone I won’t mention the name, it’s a religious group now, but the father who founded the church is a Pentecostal, the father who founded the church forgot the names of the children, he used to ask, ‘Who is your mother?’ In fact, I think the way he had it in his mind was, ‘Which is your mother out of these?’ So the child has to go down there on his knees or her knees and say the fifth, a bag of money, take a shovel …

Lizzy Attree: Were they orphans?

Charles Mungoshi: He couldn’t identify his children. All he had was just like an animal.

Lizzy Attree: So he fathered the children?

Charles Mungoshi: He fathered the children, but he had to ask the children, ‘Who is your mother?’ I don’t know whether he knew, or whether the mothers came for security or they got the children from some other man and came to him to look after the children. He had money, and he had the spiritual thing. He had this trick of those who can’t walk, shall walk, the things that I hear again in the churches, so there we go.

Lizzy Attree: I wondered whether there was any response to this story in terms of when people read the story, do they tell you what they think—are you trying to change people’s minds about behaviour? And how they suspect women?

Charles Mungoshi: I do not change people’s minds. I am on a journey finding out about myself, through many trips. In fact, I stopped somewhere, this is wonderful, I didn’t know we can think such evil, I didn’t know we can be so beautiful, I didn’t know we could look after each other, I didn’t know we could kill each other. I don’t change people’s minds, I’m worried about changing people’s minds, how many people have tried to change people’s minds?

Lizzy Attree: There’s a danger in that responsibility.

Charles Mungoshi: Exactly, there’s responsibility, I’m not Noah’s Ark! [Laughs]

Lizzy Attree: So you don’t want to be vested with authority of any kind. It’s just illustrating …

Charles Mungoshi: No, it’s simply, this is how we live. And how is it with you, neighbour?

Lizzy Attree: And how do you think people do respond to something like that, to Aids? Do you think that the way you described that has changed?

Charles Mungoshi: Aids is simply moving around, and it’s a disease and like any disease, like leprosy, like prostitution, like anything, it depends on who is involved with it, because those who are victims of that particular, whether it’s a disease or an inclination, they need pity, is it pity? Or they need love.

Lizzy Attree: Because I think the way the story progresses, even though you’re showing Damba’s development, and his growing understanding, one of the things you also show is how wrong those misconceptions can be: not that there’s a right and wrong, but you completely blur the line between the boy Dura, that they decide to dislike, who seems to be quiet, but turns out quite spiteful and by association with him, they think he has Aids, and so it’s a very passing thing but I think it’s quite pertinent, even if he did have Aids.

Charles Mungoshi: He does not know that they think he has Aids.

Lizzy Attree: No, he doesn’t know.

Charles Mungoshi: But he’s just playing pranks like any other boy. The mother said, he’s very sharp but look after him he’s got a weak chest.

Lizzy Attree: And then he gets sick from being pushed in the water. I just think that by showing that blame is not straightforward you’re complicating an issue that people want to simplify because people want to have villains, and they want to have someone to say he definitely did this for whatever reason, and he was bad.

Charles Mungoshi: What are you saying here?

Lizzy Attree: Well, I think I’m just saying, or perhaps it’s not a question [laughs] but you’re mixing a culture of blame with more of a human understanding of how people deal with fear, their own insecurity.

Charles Mungoshi: I do not think in advance of people with a culture of anything, I look at people responding or doing things to each other.

Lizzy Attree: I wondered why you chose to write the story ‘Letter to a Friend’ in the Caine Prize collection Seventh Street Alchemy from the perspective of the first person?

Charles Mungoshi: That’s a process, that’s the work in progress, but it’s been in progress for a long, long time. Irene [Staunton, Weaver Press] asked me something about Aids, and could you write something? I couldn’t write anything.

Lizzy Attree: So she asked you to write something?

Charles Mungoshi: Yes, but I had something on the fire, and had to pull something from the pot, mind it’s hot! Letter to a Friend is from something I’m doing.

Lizzy Attree: So you’re still working on it.

Charles Mungoshi: I hope so, if we don’t die tomorrow [laughs]. The whole thing is about strength and waking up to do something, in your mind.

Lizzy Attree: Because the woman actually says in the story that she doesn’t know how much it will cost to write the letter; it takes a lot out of her. I think it’s powerful to talk about how telling the truth can cost …

Charles Mungoshi: No, it’s a whole community, the people she mentions, that’s my way of writing, and she mentions these and she’s going to look into every detail, how the children, how the husband, how the mother, the father, later on I think they’re going to go to a jazz club [laughs] and they find it out.

Lizzy Attree: Is she going to bump into her father, then? Is she going to meet her father?

Charles Mungoshi: She’s looking for her father.

Lizzy Attree: She’s going to bump into him?

Charles Mungoshi: Bumping, what do you mean, bumping, I don’t understand the word.

Lizzy Attree: Just accidentally meeting, perhaps.

Charles Mungoshi: Oh, she will meet a man.

Lizzy Attree: On purpose?

Charles Mungoshi: No, the father has been looking from a long distance, looking at his lost daughter, come and find your lost father.

Lizzy Attree: So will there be different voices in the later story?

Charles Mungoshi: I don’t know. It’s something I’m working on. I say to myself, ‘Ah, this is going to be wonderful,’ and then I say, if you say it’s going to be wonderful, it’s rubbish! [Laughs] You have to listen to the way the characters are doing it. You must make sure that you respond to them, because they’ve been living with me in my mind for quite some time. That’s a strange thing, that you can be haunted by your imagination [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: Yeah, it’s quite common.

Charles Mungoshi: Comic.

Lizzy Attree: Yes, but it can be disturbing.

Charles Mungoshi: Very disturbing. Ya, you can kill yourself [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: You mustn’t.

Charles Mungoshi: No I won’t. So we try to kick it out with barbiturates and things like that: barbiturates, is that right? What is that?

Lizzy Attree: It’s a drug, it depends, you can have different ones.

Charles Mungoshi: I was very interested that while they were looking at the British Empire to go to Africa the women were taking opium or things like that.

Lizzy Attree: Really? To keep themselves normal?

Charles Mungoshi: Now you were asking about this ‘Did You Have To Go That Far?’

Lizzy Attree: I suppose they’re not really questions you can answer.

Charles Mungoshi: Letter to a Friend that’s what we have been talking about and I said it’s been pulled out of a bigger work, that hasn’t yet been written; it’s not down there, and this is a point of view that I thought I might take, she might tell her story. I don’t know whether she has to tell her story, but I thought at that point, this is the most effective way of telling my own story, and remembering things and regretting, and so on. You know, I remembered, there is a book (I haven’t read it, and, by the way, I’m worried), So Long a Letter, that I’ve heard of, but that’s so long ago. I don’t know whether you have read it?

Lizzy Attree: No, but I gave it to a friend, I know what it’s about.

Charles Mungoshi: But I suppose that kind of personal admission and personal strength, because she’s got to have some friends somewhere. She’s alone there, they are moving away as I look at them, in their minds they’re moving away from me. So I think that’s where we were.

Lizzy Attree: I think it’s really unusual to find those stories because (from the texts I have researched) people have not written fiction about HIV/Aids from the ‘I’, the first person perspective: fiction that isn’t testimonial, that isn’t real autobiography.

Charles Mungoshi: That’s why it’s been kicking in my head for, like a child to be born—no, it’s no longer a child, it’s much bigger, an elephant of twenty-one years. The story’s there: I write, the papers are all smoky and have been exposed to sun.

Lizzy Attree: For twenty-one years?

Charles Mungoshi: Not twenty-one but somewhere around ten or so. Ten would be 1990, ya, somewhere there. Actually the whole story is Saidi, who’s a Muslim …

Lizzy Attree: Also something that hasn’t been published.

Charles Mungoshi: And he plays music, and her father plays music and something happens, it has not to be very melodramatic, it must not be a story, it must be people, they are from the same root, something like that, ya. That’s the idea.

Lizzy Attree: And she sees a connection?

Charles Mungoshi: And I have to make it somehow. They have to tell me, how do we make it? That’s why they live with me. It’s not very good for real family affairs. You are living in your mind, we need bread. Ya.

Lizzy Attree: There’s no easy solution to that. It would bring back an idea of a mythic father, someone that she’s imagined, that she’s created.

Charles Mungoshi: Mythical things, those are your words, I see the story like this.

Lizzy Attree: It’s just a father, and a daughter.

Charles Mungoshi: She’s looking for her father in the letter, and the mother is not going to be left. And there is a woman who is a cachaça swiller, a gin drinker is the stepmother, that’s how it should go, I always lose my balls in the grass, I’m playing golf.

Lizzy Attree: You talk about the laughter, the way she laughs and her sort of hysterical response to knowing she’s ill. And it’s something I’ve noticed here, that people laugh when people are stressed and upset, they end up laughing. But it’s not written about, so when it appeared in there it struck a chord.

Charles Mungoshi: Well, that’s from personal life, actually it’s a relation to getting new energy; laughter is the best medicine.

Lizzy Attree: But it can be a subversive thing when people laugh.

Charles Mungoshi: Just laugh. When they laugh at you, or laugh at themselves. Well there’s a suppressive thing if I laugh at you, when I’m alone, walking down the road does she think … hahhahhh, now is that laughter, there’s a whole bellyful. There is laughter. You know this is how it works [laughs]. Then you come back to be real, what are you laughing at? To tell you the truth, shit I’m sick, I’m ill. The best thing is taking medicine, or do you go on a vendetta spree or …? I think once you laugh you sit up and look at how it is, in the middle of the problem.

Lizzy Attree: It ends without resolution this story, and I suppose if you’re writing more, then that’s partly why.

Charles Mungoshi: That doesn’t give you some idea of where she’s going, well there’s a lot of darkness, but the last sentence is ‘I didn’t know there’s so much to talk to.’

Lizzy Attree: Just talking is also as a confessional thing. Because letters are often not communicating directly to someone else, it’s more about the character who is speaking.

Charles Mungoshi: We’ll find the finer points when we go into the main thing, we have just pulled the tits out of the baby’s mouth, you have taken photographs of the tit in the baby’s mouth, we know the story, this is somewhere, something like that has happened, but the text, the context, the whole thing, it is a story that has to be done. And I’m struggling on it. It makes me get drunk, because I don’t know what these characters do. But once I sit down they talk and I can go home to it. No food, no drink, no nothing.

Lizzy Attree: Really, that’s how you write?

Charles Mungoshi: I just go on, a very pleasurable experience [laughs], finding out about myself somehow.

Lizzy Attree: Almost like the romantic poets, who believed in their inspiration coming from …

Charles Mungoshi: The muses, I am not amused [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: … the muses. They used to believe you had to be ill to write. They would deliberately contract TB, and other consumptive diseases, to be …

Charles Mungoshi: To be what?

Lizzy Attree: To reach a higher state of consciousness.

Charles Mungoshi: I think that’s for women, no?

Lizzy Attree: No.

Charles Mungoshi: No, no I think they have a feeling/thing of ‘she looks evil’, you know, consumptive and kind of something that we cannot handle, a cloud, or …? Well that’s western culture I suppose and it hasn’t shaken us.

Lizzy Attree: You refer to lots of things like the religious, the Islamic and Christian things which are going on, but this idea of something apocalyptic happening, you get those references quite a lot in western culture, and I’ve started to find them in South African and Zimbabwean literature, and I don’t know how close they are to how people feel. Is there a sense of apocalypse? Could you relate apocalyptic thinking to the way Zimbabweans think about things, is that something that’s come in from outside?

Charles Mungoshi: Apocalypse, Armageddon, it comes from outside. Ya.

Lizzy Attree: That’s what I wondered.

Charles Mungoshi: With music, with movies, that whole lot of conquering another world. That gives them thoughts so that they rub out their own thoughts; what about their God? So that we can have our God, like the superior powers, super powers.

Lizzy Attree: And so that’s from a language of war and a language of colonialism.

Charles Mungoshi: Exactly.

Lizzy Attree: And you don’t think that was here before?

Charles Mungoshi: No, it wasn’t. It was here in a way, but not on this massive global scale.

Lizzy Attree: And what about the ideas of plague, the connection of diseases and something like Aids with apocalypse—does that make sense here as a way of seeing disease as a threat, for example?

Charles Mungoshi: It is very interesting. I haven’t dealt with this, but we have forgotten God’s words, it is with those who took the western religion, the Pentecostal churches and they are making the first mistake. They have taken a dark African way of looking at things, that if you rape a little girl you get new life.

Lizzy Attree: You think they’re preaching that?

Charles Mungoshi: They don’t preach it, they don’t say it, but they go and do it. They’re in jail some of them. Leaders who pray for miracles, but somehow they get lost somewhere, they rape a little girl to get a new life, elixir or whatever, that’s the word isn’t it?

Lizzy Attree: Eternal life, what they would preach as eternal damnation, I would imagine.

Charles Mungoshi: [sniggers] Ya.

Lizzy Attree: But people in power, n’angas and others, does it relate to a more general abuse of power?

Charles Mungoshi: Even spread the germ around, don’t germ yourself, spread the germ around, give us more bread, it’s OK. We don’t know, there’s analysts, critics see what they see according to their own theories, but life happens. It’s like, ‘shit happens’ [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: But I’m trying to look at other ways of seeing things than the way I would see them, and to ask you …

Charles Mungoshi: You have to live the life, or imagine the life and live it, in a concentrated way.

Lizzy Attree: And so I’m doing that by reading the books.

Charles Mungoshi: I don’t know if we get there. Take me over across the bridge.

Lizzy Attree: And a penny for the ferryman.

Charles Mungoshi: But my most painful experience I’ve been telling about, I was given a class of children in Vermont, United States, I was telling a story, The Elephant and The Hare, and so on. They understood the language, but they didn’t get where it comes from: where we laugh, they couldn’t laugh and I felt very, very bad—I thought I was a failure because they didn’t understand me.

Lizzy Attree: But how would you have explained?

Charles Mungoshi: How could I have? No. We don’t explain how we grow up with a lot of whatever we have, and we put it in a story, you know the tip of the iceberg, that kind of thing. You know when we tell a story we can see the surface but where it comes from they didn’t understand, they couldn’t laugh and I felt very bad and I went into Famous Grouse is it? [Laughs] To kill the egg. That’s the time I really did not enjoy myself but it was a wonderful experience in the sense of how do we write, who are we writing for, what language we use, and that kind of thing?

Lizzy Attree: Well, for example in the story ‘Did You Have To Go That Far?’ there’s a song, and in the glossary it just says ‘nonsense song’, but is it meant to be funny? The children, the boys next door sing a song, but what does it mean?

Charles Mungoshi: It’s in Shona, I didn’t translate it. Who said nonsense?

Lizzy Attree: It says it in the glossary, it just says ‘nonsense song’.

Charles Mungoshi: [Sings] that’s my grandfather, my maternal grandfather, my mother’s father. He was an mbira player, they used to smoke grass, leaves, that’s why they become weak, when we take them we go, that’s an Alice in Wonderland sort of thing.

Lizzy Attree: So it’s a psychedelic reference, hallucinogenic.

Charles Mungoshi: [Sings] He used to sing that.

Lizzy Attree: So your grandfather used to sing it when he smoked weed?

Charles Mungoshi: Yup. Unfortunately I didn’t see him, but my mother talks about him a lot, and she’s a beautiful singer. And she can tell you the difference between mbira, she can tell you my father used to sing beautiful songs, and she sings for this occasion, this song.

Lizzy Attree: So why for that occasion are they singing it?

Charles Mungoshi: It’s simply things that they hear from people.

Lizzy Attree: So they’ve just picked it up. The other boy’s jealous of that song and wished he’d made it up himself?

Charles Mungoshi: No, no, no, that’s the other song. Oh yeah, it’s Pamba, thinking that Dura has got the song. It’s the way it’s sung. Because I think Dura is more intelligent than these other guys, than the storytellers, but the storyteller looks like an elderly man looking at how we played when we were children. Not quite a child—I don’t know, it’s the way you see it.

Lizzy Attree: And then there’s passing on the curse ‘kurosirara’?

Charles Mungoshi: Oh that’s … the simplest word in English is ‘scapegoat’. It is not scapegoat in the sense of simply pushing the blame on someone, it’s a really a spiritual living thing. My mistakes are caused by this thing, so I’ll get a goat, tell the goat, ah, we’ve got it in the Bible, the pigs, the pigs! Ya. Legion, that’s it ‘kurosirara’ we take the bad spirit, put it in the pigs we throw it away, korasa is throw.

Lizzy Attree: ‘Nengozi dzakumba kwavo’?

Charles Mungoshi: Ah ngozi, no that’s their bad spirits, don’t bring it around here. It is ngozi, it’s actually something inherited, it’s in your genes, and if they don’t fight it back the whole way, they made lots of mistakes and their minds are still screwed up with the mistakes that they made.

Lizzy Attree: Do you think people understand it like that?

Charles Mungoshi: This is how it works with us. Ya.

Lizzy Attree: But is it like rinyoka?

Charles Mungoshi: Rinyoka, I don’t know how it means.

Lizzy Attree: Isn’t it when a man says his wife has a disease, and if another man touches her he’ll also get the disease and it was a way of deterring infidelity.

Charles Mungoshi: Well that’s what you call this disease if you stay close with somebody. A rinyoka, I would want to believe, I don’t know, because it comes from another part of this country, but rinyoka would be something like hexing, fixing you.

Lizzy Attree: To protect or to cause pain?

Charles Mungoshi: Ya, like I’ve got a knife, and I go to a medicine man or medicine woman: if my wife is being unfaithful I’ll close up my knife, and I’ll find them still in bed when I come back from the long trip.

Lizzy Attree: A way of catching them out. So that’s from the north—whereabouts exactly is that from?

Charles Mungoshi: Guruve, or something like that—the Zambezi valley, Chinhoyi or somewhere.

Lizzy Attree: And then where would you place yourself?

Charles Mungoshi: Midlands, Chivu, Crossroads, Harare that way, Gurinmandoro that way, Masvingo that way, Mutare that way. In the heart of the heart of the country.

Lizzy Attree: And so do people have ways of explaining Aids there that are particular to that area, or disease in general?

Charles Mungoshi: We don’t talk about it. That’s my experience. We try to say, ‘the clinic says’. We call it ‘mukondombere’—that was a song by Thomas Mapfumo, he gave it that word, it’s something like a locust invasion.

Lizzy Attree: Which can also be biblical.

Charles Mungoshi: It is a very, what is it, pandemic, ya. It attacks everybody, so that’s a weaker ‘mukondombere’: Aids is much deeper, we still, I can’t say ‘they’, we still don’t want it said.

Lizzy Attree: Said out loud.

Charles Mungoshi: Ya.

Lizzy Attree: And when you write it in a story … is it dangerous to even write it in a story, if people knew you were writing?

Charles Mungoshi: No, no, it isn’t. We see it, but we don’t say it. We know it. Ah, chakauya—the thing that came.

Lizzy Attree: People also say chiwere?

Charles Mungoshi: Chiwere is disease.

Lizzy Attree: So the thing that came chakauya. Because also using that language, it makes people feel there’s nothing you can do, you can’t stop locusts, so it victimises people in a way …

Charles Mungoshi: No and especially the way Thomas Mapfumo sings about it, it’s much more message-ful (if there is such a word), to the people, but urban people don’t know about locusts, what are you talking about. You need to get a new language; it actually created a new language for the people.

Lizzy Attree: So they use those words instead. Do you think it matters, if people use Aids as a word?

Charles Mungoshi: We use Aids when we are talking in general terms, but when somebody is dying there and we are burying them, we don’t say he is dead, or she is dying from Aids. His people or her people will kill you.

Lizzy Attree: So it’s that dangerous?

Charles Mungoshi: Ya. They will take the traditional way and go and find out who killed them, because somehow, in that darkness we still believe nothing happens without something causing it. And other people who hate us use witchcraft. Our enemies, so really it’s not Aids.

Lizzy Attree: It’s something else.

Charles Mungoshi: Ya. But now we find in different corners the whole thing, little punctures there, some people stand up, ‘My daughter, my son, has died from’, we tell you young people, ‘Don’t play around, don’t fool around.’

Lizzy Attree: Do they say that at funerals?

Charles Mungoshi: They say it, ya. Some people.

Lizzy Attree: And can it only be the parents?

Charles Mungoshi: Those who are close to the one who has gone. Ya. Because those who would give speeches are the parents: the mother’s way of looking at where she came from, where he came from, who they are the father’s side, and the other relatives. So really, those who are physically directly his side. My daughter dies or my son dies, I can openly say, ‘I know. You have seen it, how he was fooling around. You have seen it, don’t go and look for other people. Don’t take the traditional road, this is ‘it’ that’s killed him.’ That’s their business.

Lizzy Attree: And does it work if someone does that?

Charles Mungoshi: Ya. I don’t know whether it works, but some people really walk away and say, ‘We knew it.’ It’s like, ‘I knew it, but I couldn’t say it.’ [Laughs] That is how it is in Zimbabwe.

Lizzy Attree: But it’s a sad thing, when the way people deal with it is to hide it, and it must come from how people are feeling …

Charles Mungoshi: Of course, it is very sad, the whole business of enlightenment, do you take Christianity or do you look into your mind, or what?

Lizzy Attree: And which one do you use as a tool?

Charles Mungoshi: I use anything handy which kills the gods [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: Do you believe in it?

Charles Mungoshi: I mean, right now I’m using Buddhism: there’s a comparison in Rumi that Jesus Christ was there and apparently a lot of people in mystic, Islam, the mystics.

Lizzy Attree: Sufis?

Charles Mungoshi: Ya, Sufis. Apparently they refer to Ben Ariam, Eid Ariam, Jesus Christ the son of Mary, they refer to what he says. They’ve got a whole history of working that way, it’s very interesting.

Lizzy Attree: Using all the teachings and writings …

Charles Mungoshi: To find something for ourselves, exactly.

Lizzy Attree: And would you call that thing that you find the truth? Or do you doubt truth of any kind?

Charles Mungoshi: ‘What is truth?’ Pontius Pilate asks, it moves.

Lizzy Attree: What about love?

Charles Mungoshi: What is love?

Lizzy Attree: You would ask the same question?

Charles Mungoshi: What is love?

Lizzy Attree: Sufis particularly, believe there’s a kind of love of God.

Charles Mungoshi: Especially Rumi, that connection, melting, the subject melting into the object that kind of thing. I wouldn’t like to call it shape, because I haven’t been there, but it sounds very real. Ya. Because he’s been able to do some things and people do some things.

Lizzy Attree: It comes back to the hallucinogenic side of enlightenment …

Charles Mungoshi: Ah, shortcuts to the experience. Well, it’s like wanting to get a kick through beer, but when you can meditate you can actually walk away and you’ve dropped your whole thing and you don’t need it anymore. Like, writing, in fact: I write satisfactorily when I walk away from the desk, and I know where I’m going to, where I’ve left the story and it works out. And I go to the pub and I’m shouting ‘Hallelujah!’—something like that.

Lizzy Attree: So it works out and you’re happy. Have you read The Doors of Perception?

Charles Mungoshi: Huxley? It was a long time ago, because there were a lot of things, there was Dr Leary and the Beatles were going around, and Dr Leary talked a lot about that kind of thing.

Lizzy Attree: Acid?

Charles Mungoshi: Actually he told me a lot about Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game.

Lizzy Attree: This is a revelation to me, I’m having my own revelation.

Charles Mungoshi: But you know your western or Græco-Roman crystal cult, I’m trying to dig the mound which is Thomas Mann in Germany.

Lizzy Attree: You’re reading it in German!?

Charles Mungoshi: No, that’s the bad thing, you have to read it in translation. I like García Lorca, he’s quite good. He’s got a light touch into deeper things.

Lizzy Attree: It’s a difficult thing to achieve.

Charles Mungoshi: Ya, it is. We’ll usually use laughter over death. We laugh at death. We bring drink! [Laughs] Do the usual thing. This is not new. This is our business. If you want to cry, go and cry. This shall pass away too.

Lizzy Attree: But it’s a longer dialogue just with mortality. I’ve been struggling with some of the stories I’ve looked at with a reluctance to be morbid, what you would call maudlin, western art and culture has always had this fascination with death, not that any other culture doesn’t, but in a kind of …

Charles Mungoshi: Maudlin?

Lizzy Attree: An almost gruesome fascination with the details of death, physical disintegration as well as the side of what happens, in paintings and in lots of literature like in Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, and Camus’s The Plague, they like to describe the nasty things so it almost becomes like a project in itself to describe …

Charles Mungoshi: They’ve got a German word for it, is it like angst or something? Like Kafka’s sort of world is it?

Lizzy Attree: It could be Kafka. [Schadenfreude]. Can you relate that to your own experience?

Charles Mungoshi: Of course, I mean we’re always shouting ‘Why, God? Why me?’ But I think it’s always covered with, ‘What do I think?’

Lizzy Attree: But does that come from an artistic temperament?

Charles Mungoshi: We don’t have a literary … we have a storytelling, we sing it.

Lizzy Attree: So it tends to focus on the happy-sad?

Charles Mungoshi: No. The sadness is heard in the singing. And when you respond, we cry together. So if I could write a song, if it could be heard the same way that it is read, then probably. I’m struggling against the current. We are not only writers. We are a visual and an audio people, especially music, the beat.

Lizzy Attree: And the way that makes you feel inside.

Charles Mungoshi: [Sings in Shona]—some of it relates to movement, sadness and whatever has happened to us, and it’s like letters. Blacks in America, jazz, easy to get until it gets very intellectual. Blues, I think. Some kind of ballads in another language: Spain, the moors, blacks were in Spain and I think that’s part of Africa. I mean we are also, we are all together. It’s unfortunate that the politicians don’t see it. [Laughs] It’s always politicians.

Lizzy Attree: I was telling someone recently about Morris Dancing, you know, dancing with sticks and it’s called Morris because it comes from Moorish. So that one thing that people think is really English, the bells and people dancing with sticks, is from …

Charles Mungoshi: Where does it come from?

Lizzy Attree: It’s from the Moors, from the Crusades.

Charles Mungoshi: Ask them where, who started it, in Norfolk, Derbyshire, or York?

Lizzy Attree: In Cornwall?

Charles Mungoshi: Or in New York or New Amsterdam?

Lizzy Attree: But it’s one of those things.

Charles Mungoshi: No I’m quite happy. What I used to like, I loved geography. I would take a map, I’d like to be there.

Lizzy Attree: And you’ve been able to go.

Charles Mungoshi: And it’s happened to me. I’ve been invited. Just work very hard where you are, you’ll get there.

Lizzy Attree: Then you can escape!

Charles Mungoshi: You can’t escape from yourself, because you are here.

Lizzy Attree: And it makes you see yourself differently.

Charles Mungoshi: But when you are here, wherever you are you can escape; OK, I think you are right. You can get out, you can look around and say, ‘Why the hell am I here?’ Just get out. But you will always, always, always be with yourself.

Lizzy Attree: It’s true.

Charles Mungoshi: Is it shit? We eat shit, eh? [Laughs]

Lizzy Attree: Eventually.

Charles Mungoshi: Finally. Exactly. Paul Celan, Jewish, German, he’s got a good poem, which I’m doing in Shona, he’s inspired me to do my book in Shona. ‘Death, when the party is over, you are the partner I hug, dance with me.’

Lizzy Attree: That’s what I mean: when you marry death, there’s that almost sexual element to when you embrace death. People used to say in Shakespearean times that when you had an orgasm, or when you had sexual intercourse, that you ‘die’; they would describe it as dying.

Charles Mungoshi: You forget yourself.

Lizzy Attree: In that moment.

Charles Mungoshi: In Buddhism it’s drop mind, drop body. And in 1253, there was a Japanese person who went to find out about Buddhism, it’s a whole culture those guys had with, there’s also a whole lot of culture in what we call witchcraft here, but then nobody has bothered to look into it deeply, researched about it. They don’t want to be asked, it’s quite interesting. If people had researched before they killed …

Lizzy Attree: And said that it was wrong before … But it must have had its uses before?

Charles Mungoshi: Like the Indian in America, same sort of thing, you kill the culture so that they’ll be servants to you. If they still believe in what they say, they will kill you.

Lizzy Attree: But now it’s very hard to find out, isn’t it, because there are so few people left, and also you get accused of intruding on a sacred culture?

Charles Mungoshi: But then they have the survival element, they came riding and raiding, a quarter of this population [from Zimbabwe] is somewhere in Luton or … [laughs]?

Lizzy Attree: That’s right.

Charles Mungoshi: And they are buying houses. Adaptation, the chameleon adapting to whatever, it’s about survival. You don’t go about asking what is in the past of a rose, but rather a rose is a rose is a rose [laughs]. Well, I’m just finding it out now discussing these things. Sometimes we are very lonely.

Lizzy Attree: It’s Harare North.

Charles Mungoshi: Is it? Luton? [Laughs] Do you believe? In what?

Lizzy Attree: No. I believe in life.

Charles Mungoshi: Exactly. It looks after us if you look after it.

Lizzy Attree: Not always. I think it’s unpredictable.

Charles Mungoshi: I’m not on my own.

Lizzy Attree: Do you believe that?

Charles Mungoshi: Well, if I take away the vegetable, the meat, or even if I take away what I eat, I am part of that, I will die. I will return in to feed these things. I am part of that. I’m not even what I think because I didn’t bring myself here.

Lizzy Attree: But somebody did.

Charles Mungoshi: It becomes those Kant and Schopenhauer, and Kafka: I read them too early in my life. They damaged my brain [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: And mine. Especially Schopenhauer. He was a nasty person.

Charles Mungoshi: What the hell. Who the hell is he? I had been reading that, actually I was fasting and doing all sorts of things in 1965, my friend comes around and gives me a book, Mein Kampf, he said, ‘Listen to this passage, this passage is very powerful!’ Hitler was powerful, he was a powerful preacher, but don’t be fooled, well, who are we to judge? Now I’m falling to clichés and … death is a cliché … [laughs].

Lizzy Attree: It’s so boring and repetitive.

Charles Mungoshi: [Laughs] we are all going to die. Lazarus, wake up! He said, ‘Well, open up.’ Are we through?

Lizzy Attree: Yes. Thank you very much.