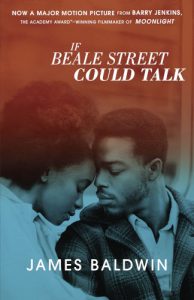

James Baldwin’s novel of half a century ago, If Beale Street Could Talk, now reissued by Penguin Random House, was successfully adapted into an Oscar-winning film by screenwriter and director Barry Jenkins. Bongani Madondo reconsiders the text and the film as part of the Transatlantic blues tradition.

He was a great master of English prose in whose style two Jameses seemed to blend most naturally: Henry James and King James’ bible.

—Lewis Nkosi, ‘To the Mountain’, Transition no. 79, 1999

For all his time in exile, and for all of the time he spent dwelling on the agonies of difference, Baldwin always spoke in a radical, cleansing and prophetic voice.

—Lawrence Weschler, New York, 2014

1.

Tish is nineteen and pregnant. Fonny is twenty-two and in jail for a crime he did not commit. They are badly frightened but intensely brave, painfully alone but very much together, lost in a world they never made but certain of each other. Above all, they are in love.

Tish is nineteen and pregnant. Fonny is twenty-two and in jail for a crime he did not commit. They are badly frightened but intensely brave, painfully alone but very much together, lost in a world they never made but certain of each other. Above all, they are in love.

This was, in 1974, the basis of James Baldwin’s fifth novel and thirteenth book overall, If Beale Street Could Talk. Almost half a century later this is also at the heart of celebrated black filmmaker Barry Jenkins’s screen adaption of the same title. Woven in—indeed, serving as the canvas upon which the main story unravels in quite a slow narrative—is the subplot of a bigger life and love story: the main characters’ love of their families, and in turn their families’ love for them.

All these interwoven tableaux of loves, of racial and romantic intimacies, take place, in the book and in the film, against the backdrop of a world, well their world, Harlem, flooded with hate. Although this is a story set in the north, New York City, the original street Beale Street is known, even to us in South Africa—indeed to all jazz- and blues-loving black folks the world over—as kind of blues and jazz heaven in downtown Memphis, Tennessee.

The title is a nod to WC Handy’s 1917 ‘Beale Street Blues’, a song whose popularity influenced the changing of the Memphis road’s name from Avenue to Street. Its role in the development and marketing of the blues has long manifested into blues lore. Among jazz and blues royalty, artists such as Louis Armstrong, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Albert and BB King, Rosco Gordon and Rufus Thomas have all played (on) Beale Street. Cab Calloway, known for popularising the zoot suit and, to a modest extent, as Hugh Masekela’s father-in-law, albeit for a brief time (Masekela was married to his daughter Chris), recorded ‘Beale Street Mama’, the 1923 Robinson and Turk song (that, interestingly, lent its title to a so-called ‘race film’ in 1946). The folk-rock poet Joni Mitchell’s ‘Furry Sings the Blues’ and the band ELO’s Time are a few among a trickle of other artists who have channelled, nodded, name-dropped or wore the street’s inspiration as part of their musical hearts on their sleeves.

Although a New Yorker and a Europhile globetrotter, in some sort of exile in and out of America, James Baldwin’s deep love and curiosity for the South—and with it, for the blues—is well documented. At the heart of his literary and ideological aesthetic stirs the blues and Southern speech patterns, what Johnny Cash refers to as ‘Southern accents’. Add classical biblical liturgy and black hymnody and the reader is sucked into a blues lyricism brimful with incertitude: always as description and spirit, words transformed into feeling and assuming a performative cadence all their own.

Baldwin wrote with the sort of mellifluous beauty that was at once Harlem bred, Southern rooted, and ultimately ethereally global—and thus, ironically, local. Local to where his reader and listener and watcher found themselves at any particular time. We are drawn from anywhere at any moment into any of his works and, by extension, his presence.

It is not readily known why he referenced this uniquely Southern cultural touchstone in his story of love between Harlem teenagers, but I know why I referenced my own chapter ‘If Esselen Street Could Talk’ in my book Sigh, the Beloved Country: after Baldwin’s 1974 novel. The man’s chokehold grip over my own work as storyteller and human being—had it not been blended into and mitigated by a truckload of secondary influences, such as Amiri Baraka (whose lacerating criticism of and later love and respect for Baldwin is a book waiting to be penned), Ayi Kwei Armah, nineteen-nineties hip-hop journalism, a genre of film criticism rooted in both satire and resistance politics by the likes of Camille Paglia, bell hooks, Armond White and Joe Queenan, for example—would have left me destroyed with envy.

Envy directed at a ghost, of course, for Baldwin died in 1986, a good two decades before I could be comfortable with referring to myself as a ‘writer’, and not merely a hack. This is, of course, the asinine and yet healthy envy writers, were they to be honest with themselves, harbour at all stages of their lives, knowing fully they’d never be half as good as the object of their inspiration’s worst work. Ever.

2.

‘Jimmy’, as those who would have us imagine they were on a first-name basis with him refer to Baldwin—usually the sort who have hardly earned such intimacy—has been a major inspiration, not only to me but to hordes of, in his language, ‘American Negro’ artists and ideologues, plus their fellows from Africa and Asia, and Latin and European parts, for yonks. His impact, in the form of literary artistry, church-derived public speaking, sartorial aesthetic, artistic and gender fluidity, and indeed his several phases of ideological and political growth, the righteous anger here, the bitterness there—especially at the collapse of what he might still have hoped would be the attainment of the American Dream, brought to ashes via the trilogy of assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Dr King—and ultimately his rhetorical flourish have had unspeakable (largely because its effect is so deep and so wide, of ‘negro’ expression yet universal experience, so rooted and so rejected; ultimately immeasurable) influence on, at least this world, in this day and age—more so than, say Nelson Mandela, in their mutually singular real times.

While he was a popular struggle figure and an underground darling for decades while incarcerated (nineteen-sixties to the nineteen-eighties), the blast of force of Mandela’s power, at least on the global scale, was largely felt in the aftermath of South Africa’s first democratic elections of 1994. The message through which it was transmitted was love: peace and reconciliation, something the current radical young garde would do well not to poo-poo. The revolutionary essence of peace as a philosophical and mobilising vehicle is just as socially and culturally transformative as the power of anger to collapse mountains and redirect the flow of oceans.

It is ridiculously unfair, bad manners even, to compare Baldwin to Mandela, but it is not, I find, unimaginable. And so: measured against the voluble media attention on Baldwin beyond the boundaries of the USA; against the sheer volume of his written and spoken output—fiction, drama, essays, film, text accompanying photography, radio and television interviews—from the late-nineteen-forties to the mid-nineteen-eighties; against the resurgence of Baldwin mania in the last twenty-five years, the last five as its apogee—Baldwin the writer, queer, liberal, black radical humanist, internationalist, flâneur, Baldwin the symbol of black transgression and global black anger, is simply peerless.

Add to that that he never really was a formal politician, never ascended to office, never recorded or released music, and never in his life featured in a film.

In his cover blurb for a reprint of Go Tell It on the Mountain, Michael Ondaatje writes: ‘If Van Gogh was our nineteenth-century artist-saint, James Baldwin is our twentieth-century one.’ Reviewing Notes of a Native Son in the February 26, 1958 issue of The New York Times, blues poet and Baldwin’s predecessor by a good two years Langston Hughes saw Baldwin thus:

As an essayist he is thought provoking, tantalising, irritating, abusing and amusing. And he uses words as the sea uses waves, to flow and beat, advance and retreat, rise and take a bow in disappearing.

One of ‘Jimmy’s’ friends, exiled South African journalist and essayist Lewis Nkosi, whose late-style prowess with the essay form and cultural criticism was inspired by, and notably a performative challenge to, Baldwin’s own lyrical eloquence and intellectual force, once said of him in a travelogue ode, ‘To The Mountain’ [Transition, 79, 1999]:

After reading the first novel [Go Tell It On The Mountain] what was striking, then, about these essays [Nobody Knows My Name], was precisely the discovery in them of the same holy-roller rhythms, the same liturgical cadences of the church sermon, so that behind the prose you imagined you could hear whole generations of Black preachers who ever bore witness in the store-front churches. James Weldon Johnson had worked the same turf when for his poetical diction he had exploited structure and rhythms borrowed from the African-American church sermon.

Young man/ Young man/ Your arms too short to box with God.

3.

Techno-logically, cinema and book-gen’read literature are oceans apart. A director who acquiesces to an author’s or publisher’s dictates, and tries to render their film as a word-for-word adaptation of the book upon which it is based, is a candidate for suicide.

Films, and books, even biopics and non-fiction, are necessarily artistically works of fiction. To create art is to render experience via tactile or technological objects into consumable documentation. At the core of all art making (religion, too) is the aesthetic urgency and agency of retelling. Thus, often, the medium dictates the shape of the message, often it is the message! Consider the following two examples of openings, both voiced by the same character, known as ‘Clem’, the young woman whose lover is in jail, in If Beale Street Could Talk the novel, and later the film.

The novel [Signet Books, 1974]

I look at myself in the mirror. I know that I was christened Clementine, and so it would make sense if people called me Clem, or even, come to think of it, Clementine, since that’s my name: but they don’t. People call me Tish. I guess that makes sense, too. I’m tired, and I’m beginning to think that maybe everything that happens make sense. Like, if it didn’t make sense, how could it happen? But that’s really a terrible thought. It can only come out of trouble—trouble that doesn’t makes sense. Today I went to see Fonny. That’s not his name, either, he was christened Alonzo: and it might make sense if people called him Lonnie. But, no, we’ve always called him Fonny. Alonzo Hunt, that’s his name. I’ve known him all my life, and I hope I’ll always know him. But I only call him Alonzo when I have to break down some real heavy shit to him.

The film

As with Raoul Peck’s docu-drama I Am Not Your Negro, the screen bursts up with James Baldwin’s words, from the git-go: ‘Beale Street’, the text jumps on the screen, ‘is a street in New Orleans, where my father, where Louis Armstrong and the jazz were born. Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street, born in the back neighbourhood of some American city, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy.’ At which point, as I sat alone in the afternoon screening of the film at the Ster Kinekor art-house theatre in Rosebank, Johannesburg, I wondered: which place in South Africa serves as our collective, metaphorical birthplace? Lovedale College in the Eastern Cape? Cape Town? Soweto 1976? Inside the courtroom of the Rivonia Trial? On the blood-spilled battlefield of Isandlwana?

But I let the thought go, as it threatened to disrupt my enjoyment of the film. Jenkins is a filmmaker known for the deep and lush fashion with which he photographs black folks in their various skin tones, and their surroundings—in gorgeous browns, sun-down scarlets, deep blues, almost always with a hint of sepia, even if in colour. His films exhort the viewer not only to watch, he invites us in to be part of the family.

Often the families are wretched, unvarnished, beautiful, ugly. He doesn’t do cinematic voyeurism, he does heartfelt characters, and that’s the beauty of him as a director.

First time we see Fonny and Tish, they are almost leisurely walking down by the river; it could only be the Hudson. Harlem is both beautiful and familiar.

It could only be Harlem, but it could also be anywhere, perhaps Alexandra township’s Pan Africa precinct, or down Gugulethu between Mzoli’s eatery and Kwa Sec jazz joint on a Sunday. The backdrop music, Nicholas Brittell’s score, sets the entire pace of the film.

Admittedly, this pace would drive a Tarantino fan up the wall. Here, the young woman, played by the gorgeous Kiki Layne with her chicory velvety skin and Afro, looks at her lover, played by Stephan James, and utters the film’s first spoken words: Are you ready for this?

It is to his and the film’s credit that Jenkins (whose Oscar-best-picture Moonlight was a cantankerous beauty and a lesson in the Eastern European less-is-more school of filmmaking, think Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog series) never indulged Baldwin’s novel’s opening monologue. While even at his worst Baldwin’s sense for the dramatic, especially his characters’s internal drama, is gold dust, he could be clanky and too layered for a drama feature. What sets the narrative up punchily in the book might prove a drag in a film.

While Baldwin’s wordiness (one of the best and worst traits all of us Baldwin’s global midnight chirrun, Ta Nehisi, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, Garnette Cadogan, Touré, Achille Mbembe even, have internalised) might deliver that free associative monologue mad-rush, or dark joy, in a Quentin Tarantino or Spike Lee film, it just feels out of kilter for a Jenkins joint. Until such a time as Jenkins is assigned to direct the sequel to Lee’s Inside Man—with Lee as the executive producer. Imagine that.

A few films had actually prepared me for this sort of pace and magically captivating realism:

- Twenty-five years ago, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, shot with poetic sensibility and lack of affectation by Arthur Jafa, dropped, made a bit of noise within the art-house circuit, then disappeared for a quarter of a century. Decades later Jafa’s visual aesthetic would be transmitted to a wokey Millennial generation via Beyoncé’s Lemonade, courtesy of his stylistic heir, Kahlil Joseph. And thus was Miss Dash’s career duly resurrected. She is now slated to direct a biopic on Angela Davis, and, as per youth argot, it promises to be lit. Someone who lights her films with similar beauty is Nefertite Nguvu.

- Also shot by the inimitable blues cinematographer of this and the previous century, the aforementioned Jafa, Nguvu’s indie beauty, In The Morning, in its location, setting, colouration, texture, pace and beautifully complicated black love at its heart can be read as Jenkins’s film’s precursor, although not the story’s.

- Read together with Dash’s Daughters—less so Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep or any of Spike Lee’s joints, with their different tempos and colour palettes—is a decades-long black cinematic intergenerational relay race of creative athletes rooted in the same tradition and playing for the same team. Winning is not at the centre of their conversation: rather, telling black lives’ stories with piercing realism, psychic beauty, complexity and ultimately in the spirit of community with its necessary differences, is.

4.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a story of love, of the inadequacies of hope, of perseverance, and, of course, of the absurdities and cruelties of black familial unity in the face of white supremacy. Its cinematic charms (on the page, on the screen) cannot lull anyone into doubt about its core message: sometimes hope, too, is not enough in the face of evil.

- Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo is an author, essayist and arts scholar. He writes on poetry, photography and politics. Regina King won an Oscar 2019 for Best Supporting Actress in If Beale Street Could Talk.