The JRB presents ‘Loadshedding’ by Michael Yee, the winner of this year’s Short Sharp Stories Award.

The Short Sharp Stories Award was established in 2013 by the National Arts Festival, and aims to encourage, support and showcase established and emerging South African writing talent.

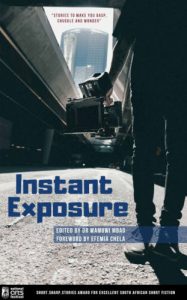

The twenty shortlisted stories have been collected in this year’s Short Sharp Stories anthology, Instant Exposure, edited by Wamuwi Mbao.

Instant Exposure

Instant Exposure

Edited by Wamuwi Mbao

National Arts Festival, 2019

The judges said of ‘Loadshedding’: ‘It’s experimental in form and style; the dialogue is strong and believable. Yee is in full control of his prose, and succeeds in whisking together all manner of grit and colour with his distinct lyricism, blending and contrasting images with ease.’

The Short Sharp Stories Award runners-up this year were Stephen Buabeng-Baidoo, for ‘Wi-Fi for the Most High’, and Shubnum Khan, for ‘Digging up Boxes’. Vamumusa Malusi Khumalo received an Honourable Mention for ‘Durban Nights’.

~~~

Loadshedding

‘To live with ghosts requires solitude.’

—Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces

He:

The lights went out, blinding him. Voices from the TV rose like lost souls through the ceiling. Darkness swallowed him whole, the kitchen whole and colour and light and time.

‘Damn it. Not now!’ he said looking up like a blind person.

‘It’s fine.’

‘It’s not fine. How is me having to cook in the dark fine?’

‘Tell you the truth I’m not even that hungry.’

He glared at her, eyes bright with dead light.

She:

‘Damn it. Not now!’

‘It’s fine.’

‘It’s not fine. How is me having to cook in the dark fine?’

‘Tell you the truth I’m not even that hungry.’

She sat on the high stool, bare feet swinging over the tiles, feeling his glare. ‘Stop,’ she said.

‘Stop what?’

‘That passive-aggressive shit.’

‘You can’t even see me.’

‘I can feel you doing it,’ she listened to him walking away from her to the cupboards.

‘Fucking Eskom!’

She rolled her eyes.

‘Koko, Singh, Molefe, they make me sick, all of them.’ He started banging pots around, taking this out on her, when tonight was his idea. He asked her to come. Him.

‘Can’t you just chill? I mean, it’s our last night and everything.’

He:

‘Just chill?’

‘Ja, what’s the big deal?’

‘Can’t you see?’

‘Uhm … little hard right now?’

‘I do everything around here!’

‘Now that’s unfair, tonight was your idea.’

‘You know damn well what I mean, the whole time we were together,’ his voice trailed off.

She:

Her black hair, which touched her shoulders, shook as she sighed.

He:

‘You know what I realised the other day? We were together one-third of our lives. One-third. That means one in every three breaths I ever took was with you.’ He ripped off his work tie and waved his small hands in the dark. ‘So sorry if that meant something. Sorry if I couldn’t let that go without one last fucking meal together.’

She:

As her eyes adjusted objects stepped out of the gloom: the microwave, the spice rack, the oven, their edges melting, becoming other things. Would he punish her if she got up and left him now? Would he withhold her half of the money from the sale of this house? Was it in him? Not long ago she would have said never, but she was seeing another side.

‘Say something!’

She stopped biting her hair. ‘Hey, why don’t I go grab us a pizza instead?’

‘What? No, man, why?’

‘No, it’s fine, the place up the road uses wood burning ovens.’

‘It’s like speaking to a brick wall, Jesus!’ he kicked the table.

‘Don’t talk to me like that!’ her chair screeched as she rose.

‘Don’t go,’ she heard him sigh. ‘How long will you be gone?’

‘Twenty minutes?’

‘I meant on your big trip.’

‘I don’t know. A year maybe?’

‘Can we talk about us after that?’

‘Sure,’ she added, ‘but you should get on with things. You know? Don’t wait for me. It’s healthier that way.’

‘Healthier for you, you mean. Fuck you.’

She fetched her handbag and her keys from the table. She was about to open the front door when he grabbed her shoulder. ‘Get off me!’ she twisted away.

He held up his hands. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘I shouldn’t have come.’

‘Look, the lights will be on soon. Don’t go, please.’

Her hand was in her bag, clutching the car keys so hard it hurt, but she couldn’t leave now. The house. The money. He couldn’t be trusted and so she turned on her cellphone and cleaved through the pitch, entering the lounge she raised the phone and cast wide the circle of light in the room.

‘Where’s the candles?’ her eyes searched the shabby chic mantelpiece, under the papier-mâché head of the deer.

‘First aid kit,’ he shouted from the kitchen.

She found it there on the bookshelf and opened the lid and scratched amongst the plasters and safety pins. ‘They’re not in here!’

‘Look for them!’

‘I’m telling you they’re not … found them.’

He:

He deveined the prawns by the sink, using one of those torches with hundreds of LEDs. Then he brought the camping stove out from the pantry and put it on the table, turned the valve, struck a match, a blue lotus hissed and bloomed in the dark. After he had brought his bisque to a boil, he added scallops, prawns and roe, concentrating the flavour. He dipped a spoon in, blew on the steam, tasted. A hit of umami lit up his frontal lobes, triggering something his colleagues had said months ago when he first told them his wife wanted to separate: ‘You should start a family,’ Ndoro said. ‘Nah, don’t listen to him bru,’ this was Austin. ‘Girls wanna have fun. Good times, man. Good times keep the lights on.’

She:

The waxy bottom of the candle was held over the match until it softened and could cling to the mantelpiece. Then she went to sit on the sofa and stared at the candle flame until her eyelids grew heavy. It went missing, whatever you call it. One day it was there, and then, poof.

He:

Broth boiling, miso melting. He made this exact dish for her the day they moved into this house. Did she notice? Course not! Serves him right, he was always a driven little turd. Working nights, weekends, holidays, trying to elbow his way past the other middle managers; working nights, weekends, just to stand still. When he looked up she was gone.

She:

She kept fighting with the cushions on the sofa. Laid her head down, at last, only to find that the armrest smelled like the back of his neck. She sprang up. Jumped off the sofa. Went to stand over the candle so the heat would scour his scent from her nose. Did time reverse everyone’s polarities? She regretted staying so long, wasting precious time. But it was always a feeling, never a thought; took years to distil into inchoate words, wrestle into a sentence, to say out loud: ‘We make each other sad.’

He:

‘Dinner’s looking good,’ he shouted. He waited a while. ‘Hello?’

‘Hmmm.’

He imagined her staring into the dark, dream-soaked eyes; he had always loved that about her. Could he win her back? Even now? He still loved her, well, he loved who she was, what they had, they were happy once, you don’t throw that away, an epoch, fair to say, you just don’t. ‘So, the estate agent’s got viewings lined up with potential buyers tomorrow,’ he said.

‘Great.’

‘We can still cancel though, you know, think it through a bit more.’

No answer.

He turned off the stove and went to splash water on his face.

She:

Smooth soles slapped softly on ceramic tiles, her hand cupped the candle flame all jumpity as she entered their old bedroom. She pressed her cheek against the pane of the French door and looked out into the back garden all bruised by the night. Marriage is never having to face the dark alone, but cowering over the light of togetherness, the cost is dear. Not an earthshattering insight, but her own, she hopes, not something that had filtered through her vanities to emerge like laundered money, the source wiped clean from memory, let it not be, please. She desired optimum growth from this experience and so, clichés were the enemy, rungs leading down the ladder, instead of skyward, where she longed to be.

He:

She had abandoned him in the shell of their marriage. Left him alone long before she had the guts to say it was over. How could he forgive her for that?

She:

She loathed clichés. Her exhaustion was a cliché. Her ennui was a cliché. Ennui? How pretentious. She was bored, plain bored. Depressed? She hated that word. Middle-class pain. Facsimile suffering. A corpse trapped inside a zero-carb body. Millions of less privileged South Africans would give anything for a fraction of her life and still she couldn’t give a shit. What was the word for that?

‘Hey, why so quiet? You alright in there?’ his voice barged into the bedroom.

‘I’m ok.’

‘Ok, well, dinner’s almost ready.’

He:

Since she moved out of the house he had been receiving flashes from the past, like radio signals forever moving through space. And now, as he groped for the soup bowls in the cupboard, another transmission:

They were in a shopping mall, side-by-side, skin glowing, god-fearing, that young, that whole.

‘They say couples who hold hands stay together.’

‘Who says that?’

She shrugged.

He was enduring yet another frigid spell, and so when she reached for his hand he pulled away. This was the moment they broke, yes, he was certain. He remembers her fleshy palm, her long fingers, shaped like the hole she had punched through his heart.

She:

She pressed her ear against the hardwood floor, listening to the house creaking. She opened her eyes. A white box was under the bed. But how? It should have been in her parents’ garage. Just the other day she had come to collect it along with all her other things. Didn’t she? She disappeared up to her elbows, and retrieved it from the bed.

He:

He wanted to rush into the bedroom screaming at her. It’s like this. One minute he wants her back. The next he wishes she were dead. He picked up the carving knife and ran it against his neck instead.

She:

Mothballs clattered as she lifted her wedding dress. She held it against her chest, watching her reflection in the window. How many selves had she tried on since she last wore this wrinkled thing?

He:

The pot lid rose in his hand, and aromas, transforming this little pocket of Pretoria into an Osakan district, but he didn’t care. He was staring into the bright past, receiving another transmission.

She:

She lifted her arms and pulled the dress down over her t-shirt, then wriggled like mad as the dress refused to be bullied past the hips of her jeans. She pulled and pulled until eventually she fell over, out of breath, staring up at the ceiling, she smiled. She had met someone a few years ago. Out of the blue. She was forty, but still young enough to believe that following your heart was like Polyfilla. Righting all wrongs. Filling all cracks. Instantly unfucking her fucked-up-ness. Christ, she shouldn’t even be thinking about that right now. Not with him in the kitchen; once they were so close, they could speak without words.

‘Dinner’s ready!’

‘Coming!’ she struggled out of the wedding dress, abandoned it on the floor and walked into the kitchen, shone the candle around. ‘Where are you?’

‘Out here!’

She found him standing on the balcony. Two yellow soup bowls and a copper saucepan were on the patio table. Dragons of steam rushed out as he lifted the lid in the moonlight.

‘Come, before it gets cold.’

He:

She walked straight past the steaming pot.

‘All your favourites in there: mussels, clams, is there enough miso? Have a taste,’ he snapped.

She leaned on the balcony rail and watched the spill of freestanding houses, pitch black in the valley of the veld below. ‘When will the lights come back on?’

‘Never,’ he smirked. He saw her shaking her head and then storming off to the far side of the balcony. The Weber screeched against the terracotta tiles. ‘What are you doing?’ Logs, which he had split ages ago, thundered as she threw them into the black kettle drum.

‘Where’s the firelighters?’

He tried to stare her down.

‘Tell me.’

He pointed to the lemon tree.

She found it behind the pot plant, wiped away the cobwebs and ripped open the packet. Small waxy blocks smelling of kerosene were placed under the logs. Soon, she was conjuring flames.

‘You know if you wanted to braai you should have just said.’

‘I don’t want to braai.’

He dished up for himself and threw the ladle back into the pot.

She:

The smell of the soup was making her naar, that’s why the fire. She felt better as soon as the wood began to snap and she breathed in the dry smoke.

‘Hey, it’s gonna be okay,’ she said. He looked so pathetic, staring at his soup, she forced a smile, didn’t take it to heart when he ignored her.

He:

Just like old times, eating alone.

She:

It was better near the fire, warm on her face. She closed her eyes. Flames hit the wood like axe heads. Crickets sang under the stars. Dogs howled behind high walls. A cupboard door banged open. Loud as a gunshot. From the bedroom. The hairs on her neck stood on end. Her eyes grew wide. She froze. House invasion.

He:

Sounds are brighter in the dark. He heard books, boxes and shoes sparking as they hit the bedroom floor. The house keys lay on the patio table. He lunged for them, pushed the panic button. ‘Fuck.’ He aimed the fob at the white box shaped like the badge of their security company, high on the balcony wall, mashing his thumb on the button the alarm refused to sound.

She:

‘I didn’t lock the front door. Oh God. Did you lock the door?’ her hand flew to her mouth.

He:

The patio chair settled silently against the wall. He climbed onto it and opened the cover of the alarm box. The circuit board was bleeding rust. The gutters above. The rain had leaked in.

‘Call the police,’ she said.

‘My phone’s in the kitchen,’ his eyes were wide as the soup bowls.

Something made of glass exploded in the bedroom.

He put his finger on his lips, shut the sliding door and locked it with the house keys. The flames of the Weber fell silent as he put the lid back on.

Her eyes screamed, what now?

He walked past her, crouched down in the corner on the far side of the balcony, he whispered, ‘Don’t expect me to die for you.’

She:

Her legs. She held onto the balcony rail for support and waded, as if through quicksand, trying to get as far away from him as she could.

‘Come back here,’ he hissed.

She stared through the sliding door he had just locked. Something was moving inside.

‘Did you put something in my drink?’

Was it confusion in his eyes?

‘Did you?’

He shook his head.

He:

Her hand was shaking as she pointed into the living room. He frog walked back to her side of the balcony and peeked through the sliding door. The living room was so dark inside. He adjusted his glasses. It felt like cold water down his back. A wedding dress stood under the ceiling fan.

She:

At first she thought he had drugged her drink, but no more. The blood had drained from his face.

He:

Oh Jesus, oh Jesus, oh Jesus.

She:

The soup grew cold on the table. The clams went off in their shells. The tap dripped alone in the kitchen. Face pressed against the sliding door, she cupped her hands around her eyes and peered into the darkness inside. The wedding dress wore an art deco Juliet cap lace and tulle veil, it had a bateau neckline with collarbone curves, from which long sleeves tapered into arrowhead cuffs, while white satin cascaded from the bodice in an A-line, ending in a train that swept the tiles as the dress walked towards the sofa, carrying a wedding suit in her arms.

A minute passed, or five or ten; darkness stretches time. The wedding dress lay the suit like a down corpse onto the sofa.

He:

Clutching his chest, he slid down onto his bum and sat with his back against the sliding door. Objects started to fall inside, but he couldn’t turn around, he couldn’t breathe.

She:

With her face still against the sliding door, she watched the dress flinging books off the shelves with its empty sleeves, it was looking for something.

He:

A flash of pain shot through his right arm and the side of his neck.

She:

Hidden behind the dusty holiday road maps, the dress found a stack of old photos and threw them onto the floor. They scattered like leaves on the tiles, under the sofas, even as far as the coffee table.

He:

Knowing the cost if he lost, he wrestled his heartbeat down, down, down.

She:

The dress dropped to its knees, bent low and sniffed at the snaps like an animal, only stopping when it had reached the coffee table and sniffed at the photos there. She couldn’t see what it was from the other side of the sliding door, but the dress held a photo against it chest, only one.

He:

Better, but still too weak to stand, he kept massaging his heart, still a fist in his chest, but unclenching now; while the house keys became a knuckle duster in his other hand. In spite of what he had said, whatever stepped through that door would pay.

She:

The dress went back to the sofa and held the photo against the moonlight, at an angle so that the suit could see. She opened the sliding door and stepped inside.

He:

No! No! No!

She:

The dress threw her arms around the suit, which had become substantial, its hollows perhaps buoyed by the memory contained in the photograph. Now standing just a few feet away, she could see clearly now what it was. A holiday snap. Younger versions of themselves stood on a bridge. He had his arm around her, her shoulders were back, her head was up, he was squeezing joy through her eyes.

They:

The microwave beeped three times. Voices ballooned from the TV. Lights blazed.

He:

Coruscated corneas. Hammering light.

She:

Stunned, blinded. When at last she could see, the dress and the suit lay in each other’s arms on the sofa, but only the ceiling fan was moving. A hand touched her shoulder. She spun around.

They:

‘C’mon, let’s go,’ he hobbled past her, still rubbing his chest.

‘Go where?’

‘C’mon,’ he said.

She looked at the mess in the living room. ‘But the viewings.’

‘I’m cancelling.’

‘You can’t.’

‘Watch me.’

She:

There at the sofa, she picked up the dress in her arms.

‘Don’t touch it,’ he said.

She carried it to the balcony, uncovered the Weber and threw the dress inside, blew life back into the coals. Flames galloped up the mountain of satin. The lace made a crackling sound and turned to ashes that rode the rising thermals, then made a leap for the stars. She went to fetch the wedding suit and the photos and watched them burn.

He:

It was too much. He went to sit in the kitchen, relieved at his steadier pulse.

She:

She walked into the kitchen carrying the soup bowls from outside.

‘How are you not freaked out by this?’

She left him alone in the kitchen for a while and returned with the heavy saucepan.

‘Did you hear what I said?’

‘You think I’m not freaked out?’

He watched her pour his soup down the drain. ‘What do we now?’

‘We clean,’ she opened the tap.

He:

She washed, he dried. She packed, he swept. Something told him this was their last night together and so his eyes became cameras recording the details.

After they had cleaned the kitchen and the living room, they went out onto the balcony, doused the fire and emptied the sludge into a bucket, which was flushed down the toilet.

Only the bedroom remained.

On his knees, dustpan in hand, while she returned boxes to the cupboard, he picked up pieces of the broken vase by the bedside. Working with her again felt familiar and yet terribly new. Some part of him kept planning their dinner for tomorrow night, not sure if this was the past and the present.

‘Damn it!’ he stared at the long shard of glass. Blood poured from his palm, she came running.

‘Shit, shit, idiot.’

She:

‘Keep it elevated.’ She led him by the arm into the bathroom and held his hand under the tap. He pulled away. ‘Don’t be a baby.’ She eased his hand back, he gritted his teeth as water streamed over the gash.

‘How bad is it?’ he couldn’t look.

‘We might need to amputate,’ she smiled as she opened the cabinet and scratched around inside. ‘This is gonna hurt, ok?’ Hydrogen peroxide bit into the wound as she poured.

He tried to hide the pain.

‘Embrace it,’ she cringed. He deserved better, but all she had was this cliché.

He smiled at her.

It reached his eyes. Would anyone love her more?

He:

They left the bathroom together. He was still glowing like a paper lantern as they surveyed the living room, everything was in its right place.

‘What do you think? Would you live here?’ he asked her, still glowing like a paper lantern inside.

‘How much we asking?’

He told her.

She:

Clutching her handbag, she walked to the front door, turned the brass handle and held the door open for him. ‘Shall we?’ She drove her white Hyundai out of the driveway and onto the road, resisting the urge to glance at her rearview mirror.

He:

He followed her in his own car, with his headlights on in the near dawn, weaving through the short streets named after Highveld flowers. When they reached the main road, they drove for a few more kilometres until she stopped at the intersection. He pulled up beside her, their cars filling with electric street light. He put his indicator on. The traffic light changed to green. He turned left.

She:

She turned right.

They:

The:

Th:

T:

:

.