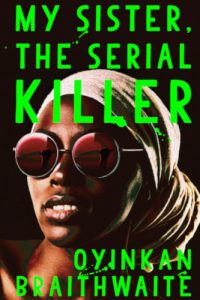

Contrary to what the title and pulpy cover seem to suggest, My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite is a novel of understated authenticity and gentle power, writes Jennifer Malec.

My Sister, the Serial Killer

My Sister, the Serial Killer

Oyinkan Braithwaite

Penguin Random House, 2018

As the African literary community discovered anew this week, writing about the taboo is a fine art. In the hands of an inexperienced or unskilled author, purportedly literary explorations of murder, incest, sex or death can quickly turn sensationalist, mawkish, or just plain offensive.

In her 1967 essay ‘The Pornographic Imagination’, Susan Sontag wrote that people, in their daily lives, have a moral and pragmatic obligation not to ‘venture into the far reaches of consciousness’, as in doing so they risk jeopardising the social order. However, she added that the ‘humanistic standard proper to ordinary life and conduct’ should not be applied to art: ‘It oversimplifies.’ At the same time, Sontag believed that what separated trashy or pornographic writing from literature was that the former possesses ‘only one “intention”’—to shock, to induce sexual excitement—while ‘any genuinely valuable work of literature has many’.

While Sontag was writing specifically about pornography, her observations can usefully be extended to other types of ‘trashy’ fiction. Which bring us to My Sister, the Serial Killer, the slim debut novel of Nigerian author Oyinkan Braithwaite, which, contrary to what the title and pulpy cover suggest, happily demonstrates the multifarious intentions of Sontag’s ‘genuinely valuable work of literature’.

My Sister, the Serial Killer opens with our protagonist, Korede, scrubbing a bathroom floor. Her sister, Ayoola is watching:

I soaked up the blood with a towel and wrung it out in the sink. I repeated the motions until the floor was dry. Ayoola hovered, leaning on one foot and then the other. I ignored her impatience. It takes a whole lot longer to dispose of a body than to dispose of a soul.

We discover this is not the first time Ayoola has called on her sister to help her clean up a bloody scene, or get rid of a body. In fact, it is the third time, and as Korede has learnt from concerned late-night internet searches, ‘Three, and they label you a serial killer.’

The setup may be outlandish, but within it Braithwaite constructs an affecting and uncannily accurate portrait of a sibling relationship. Korede, the elder sister, a nurse, is sensible, responsible, and plain. Ayoola, the younger, a fashion designer and Instagram entrepreneur, is spoilt, self-centred and beautiful. In a scene any responsible elder sibling will relate to, when Ayoola telephones Korede to help her clean up crime scene number three, Korede has just settled down to a comfortable night in:

I was about to eat when she called me. I had laid everything out on the tray in preparation—the fork was to the left of the plate, the knife to the right. I folded the napkin into the shape of a crown and placed it at the centre of the plate. The movie was paused at the beginning credits and the oven timer had just rung, when my phone began to vibrate violently on my table.

But she doesn’t get angry—neither at her sister’s behaviour, nor her post-manslaughter indolence. She feels exasperation, especially when Ayoola thoughtlessly invades her personal space in her bedroom, or forgets to play the part of the ‘concerned girlfriend of a missing person’ on social media, or when her mother blatantly favours her younger child, but in her loyalty to her sister she is resolute.

At the same time, Korede knows to keep her distance. Partly because she knows her sister is trouble, and partly because she is secretly in love with a handsome doctor, Tade, and she knows that if he lays eyes on Ayoola it will dash her chances with him conclusively. Of course, Tade does meet Ayoola, and within a short period of time is determined to propose to her. By this time Ayoola has added to her homicidal tally, and her solipsism, flightiness and lack of remorse have not endeared her to us. (‘Only the guilty go to jail,’ she blithely tells her sister when evidence that incriminates both of them is discovered in a missing man’s flat.) But her beauty has blinded Tade, a usually intelligent and sensible person, to the extent that when Korede bluntly asks him ‘what makes her special?’, he replies:

‘She is just so … I mean, she is beautiful and perfect. I’ve never wanted to be with someone this much.’

I rub my forehead with my fingers. He fails to point out the fact that she laughs at the silliest things and never holds a grudge. He hasn’t mentioned how quick she is to cheat at games or that she can hemstitch a skirt without even looking at her fingers. He doesn’t know her best features or her … darkest secrets. And he doesn’t seem to care.

And just like that, despite her broken heart Korede reminds us of the depth and span of her love for and intimate knowledge of her sister. Similarly, in one of the final scenes of the book it emerges that when it really matters Ayoola, despite what we may think of her, reflexively protects Korede, with little concern for her own safety. These moments underpin the delicate and pleasantly surprising depth of character in the novel.

Relievedly, Braithwaite has resisted any pious urge to position My Sister, the Serial Killer within a troubled political history or ‘vibrant’ cultural context, although Lagos peeps in here and there, temperamentally, with its ‘never-ending car horns, the shouts of hawkers and tires screeching on the road’, or its ‘rain that wrecks umbrellas and renders a raincoat useless’. Braithwaite does, however, allow herself full use of the tragicomic opportunities afforded to a crime novel set in Africa. The police are humorously—and usefully—inefficient and corrupt; at one point, while driving the car she used to transport a body, Korede is able to talk herself out of a ticket with some wheedling pidgin, even though it strikes a false note on her middle class tongue—‘Oga abeg, let’s sort am between ourselves’—and a medium-sized bribe. And when the wealth and status of one of the Ayoola’s victims makes his death too high profile to ignore and her car is finally impounded, Korede is confident that her homely cleaning skills will defeat the lax arm of the law:

Some of the blood has seeped into the lining of the boot. Ayoola offers to clean it, out of guilt, but I take my homemade mixture of one spoon of ammonia to two cups of water from her and pour it over the stain. I don’t know whether or not they have the tech for a thorough crime scene investigation in Lagos, but Ayoola could never clean up as efficiently as I can.

Importantly, whether Ayoola is guilty or not is left to our judicious imagination. After five deaths we strongly suspect she is, but in all but one she claims to have been attacked by the men in question, and that she killed in self-defence (the other, she says, was mere coincidence). Ayoola’s beauty is of the sort that encourages irrational behaviour from rational men—the femme fatale that should be confined to fantasy, but that is very much evident in the world’s everyday reality—and leaves us wondering, ‘Could she? … Did he?’ By not providing any evidence for or against, Braithwaite almost seems to be testing out a fable for the #MeToo movement.

With its short chapters, each with an edgy, one- or two-word title—’Instagram’, ‘Knife’, ‘Mascara’, ‘Blood’—My Sister, the Serial Killer skips along breezily, even as the body count rises. But through glimpses into the past we begin to learn more about the women’s late father, and a darkness emerges at the edge of the story. It turns out that Ayoola did learn at least one lesson from her big sister, and the novel neatly, and grimly, turns the tables on the idea that beauty is always a blessing.

To return to ‘The Pornographic Imagination’: interestingly, Sontag disagreed with the idea, still commonly held today, that in order for a work to be considered ‘good literature’ the author should have ‘the proper “distance” from his obsessions’. Instead, she asserted:

What makes a work part of the history of art rather than of trash is not distance, the superimposition of a consciousness more conformable to that of ordinary reality upon the ‘deranged consciousness’ of the erotically obsessed. Rather, it is the originality, thoroughness, authenticity, and power of that deranged consciousness itself, as incarnated in a work.

Fifty years later, an effervescent story about a glamorous serial killer is, thankfully, no longer considered an indication of a ‘deranged consciousness’. But we needn’t fear in any case, as the value of My Sister, the Serial Killer is demonstrated by its narrative originality, the gentle power of its examination of family dynamics and the harrowing legacy of abuse, and the understated authenticity and strength of its women characters.