In La Bastarda we find a revolutionary piece of literature, where a young girl isn’t saved by her long-lost father, but by herself, writes The JRB Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela in our Temporary Sojourner series.

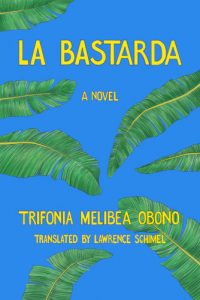

La Bastarda

Trifonia Melibea Obono (translated by Lawrence Schimel)

Modjaji Books, 2018

‘When I grow up

I want to be a forester.

Run through the moss on high heels.’

—Fever Ray, ‘When I Grow Up’

I like to read particular books at a certain time in a certain place. My favourite books to read on planes, trains and buses are ones that unnerve other passengers with their titles, like Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting and the cannibalistic anthology of new fairy tales, My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me. There’s nothing quite like other people being needlessly embarrassed on your behalf while you’re reading a good book, enrapt.

The latest book to be added to my collection of eyebrow-raising public reads is La Bastarda by Trifonia Melibea Obono, which got quite a few stares on the Gautrain. It was originally published in Spanish by Flores Raras in 2016 and is banned in Equatorial Guinea, its author’s home country. An American edition, translated by Lawrence Schimel, was brought out this year by The Feminist Press in New York and, in South Africa, by Modjaji Books.

The bastard child of the title is the sixteen-year old narrator, Okomo, a plucky young Equatoguinean girl who tries to define herself outside of the identity foisted on her by her family and her tribe—the Fang. She lives with her ornery uncle, the claw-footed Barefoot Osa, who rules his compound by pitting his wives against one another and subjecting his family to long lectures about the glorious exploits of their male ancestors. He is cruel to Okomo and as soon as her period starts makes it clear that it is only a matter of time before she will have to submit to the rule of another man, her husband.

Okomo takes after her mother, who died in childbirth. According to the accounts of those who knew her:

‘She never learnt her place in the Fang tradition. She lived much too freely.’

But it is her missing father whom Okomo puts on a pedestal. Ever curious, she undertakes serious detective work to find out more about him and where he might be. She feels she cannot move forward without resurrecting this figure from her past. No one in the village sees her as anything more than a girl to be bartered, and she hopes that if she finds her father she may be able to escape the forced eyebrow tweezing and days of endless housework and dowry negotiations that are imminent.

For Okomo, her abuela, or grandmother, cuts a pitiful figure. She is no longer fertile and sometimes finds herself in machete fights with her sister wife. Barefoot Osa no longer sleeps with her abuela, preferring the sexual company of his younger wife (and prostitutes), but she is determined to win him back. She seeks the advice of the curandera, or healer, who demands the princely sum of 50,000 francs to help her regain her husband’s interest. It doesn’t escape Okomo’s notice that although her abuela strictly follows Fang tradition she finds herself at a constant disadvantage while her male counterparts flourish. She begins to plot her escape.

Okomo’s accomplice, and one of the most lovable characters in the book, is her gay uncle, Marcelo, who lives with Restitua, a local prostitute, and sometimes his boyfriend, Jesusin. He is one of the last links Okomo has to her mother and serves as an alternative role model for his tomboy niece. Marcelo decouples sex from duty, seeking his own pleasure instead of curtailing it and pursuing it within the bounds of Fang tradition. He fails to consummate several marriages with women and when he is called upon by his family to sleep with his brother’s wife so an heir can be born he refuses. Like Okomo he is an outsider, called fam e mina or ‘man-woman’ by most people in the village. Everyone blames him for the drought and the failing crops. When he narrowly escapes being burnt to death by the villagers, he makes a bid for freedom in the jungle and leaves Okomo a comforting letter with the name of her father’s village in it.

Throughout the novel, nature calls to Okomo. In the forest she first explores the bounds of her sexuality with three girls who call themselves ‘The Indecency Club’. At first she is reticent, but Dina, who ends up becoming her girlfriend, says:

‘You’re in the forest—the Fang forest is a free space.’

Equatorial Guinea is the only country in Africa that has Spanish as an official language, and the country’s former colonial ruler haunts the characters in the book, as a place where unnatural things come from. When Marcelo cremates his father, this in the Spanish tradition, a practice viewed by the Fang as an abomination. And although Marcelo is pointed to as a threat to the livelihood of the village, the true problem are the mitangan, the Spanish settlers who overfish the rivers.

Obono is clearly highlighting, here, that notions of what is ‘natural’ and what is ‘unnatural’ are subjective and not as fixed as the Fang would have them. Homosexuality is natural and African in this book: the story’s underlying perspective is that it has existed in Africa for centuries as a mode of sex and love and is not a Western import. By contrast, the village, fettered by tradition, is uncovered as a place of some horror, where duplicity, mob justice and infidelity wreak havoc on individual lives. In La Bastarda, family members dispense cruel punishments in the name of protecting the appearance of morality. When the Indecency Club is torn apart and its members exposed they face a terrible fate. Linda is sold to her father’s creditors to pay off his gambling debts; Dina is forced to leave the village, marry her brother-in-law and become the mother to her dead sister’s children; Pilar disappears and we later find out she has become pregnant by her father, who has been raping her since she was a child.

Meanwhile the forest, which in African literature is often represented as a fearful place, full of spirits and danger (think Amos Tutuola, Chinua Achebe), turns out in La Bastarda to be a kind of utopia, where the characters set up a secessionist queerdom. In this, the first novel by an Equatoguinean woman to be translated into English, we find a revolutionary piece of literature, where a young girl isn’t saved by her long-lost father, but by herself.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing Editor Efemia Chela on fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the seventh article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.