Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater is a striking, startling, butterfly-net of a novel, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

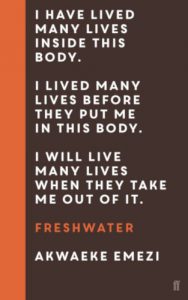

Freshwater

Freshwater

Akwaeke Emezi

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2018

Frank Kermode once described a Wallace Stevens poem as ‘a sustained nightmare of unexpected diction’. That sentiment could well apply to Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater, a novel curious and frustrating in equal measure. As a debut, the book teems with invention, innovation and boldness. It is a striking, startling, multilayered story that, in truth, deserves greater critical response than the modern reading industry’s inexhaustible neophilia allows. Emezi also deserves extensive praise in particular for travelling widely into the exotic reaches of the mind through their writing.

This unconventional novel tells the story of Ada, a baby born of mixed parentage who arrives in the world accompanied by a chaos of spirits, awakened at her birth when the gates between the spirit world and the world of the flesh are left open. ‘The first madness was that we were born,’ they say, ‘that they stuffed a god into a bag of skin.’ By this, the spirits mean that rather than becoming a unitary whole with their host, they retain their own interests and preoccupations, as well as the wrenching awareness that they are dislocated from the realm of the gods: ‘We were sent through carelessly, with a net of knowledge snarled around our ankles, not enough to tell us anything, just enough to trip us up.’

If you aren’t at least cursorily familiar with Igbo spiritual concepts, the idea of the ogbanje may initially be confusing. Thankfully, it travels fairly well in Emezi’s prose, and even if you haven’t read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, you’ll soon have your bearings. The ogbanje is a mendacious spirit that manifests as a child that cannot remain in the living world for very long. An ogbanje’s modus operandi is to come and go, and so one trapped in the world of the living will rage and tear at its cage.

As Ada grows, so the reach and the power of her accompanying spirits grow stronger. The novel becomes an unusual sort of Bildungsroman, in which Ava becomes not so much a character as a site for the rolling, heaving contestation of her divided selves. The ogbanje regard Ada as a mere vessel (one of the multiplied spirits calls her ‘the Ada’), and her parents as instruments in the attainment of their perturbations. Ada’s father is inconsequential, and the spirits conspire to drive her mother away. With Ada unsheltered, the spirits are free to disorder her world.

Dreams, night terrors, insanities, sex: these are the ways the spirits manifest in the real world. The novel moves deftly here, inhabiting Ada’s interiority as she is spirited away under the possession of the ogbanje. ‘I don’t even have the mouth to tell this story,’ she says in one of her infrequent appearances, conceding that we may as well have the narrative from the spirits, since they are the truest version of her. Here, the novel is uneven in its gifts. Asughara, the assertive spirit who takes over whenever something traumatic happens to Ada, is rendered with dexterity, but another incarnation of the ogbanje sounds alarmingly like Gollum. This self knows words like ‘rowdy’ and ‘boisterous’, but refers to Ada as though she were an object, and the conceit strains at the reader’s patience.

The trickiness in making such multiplicity legible becomes evident in a novel that bears the smudges of its debut status. Like many recent fictions, Freshwater is taken up in form and content with the mimetic capture of quiddity—the reduction of pure essence, pure character to words. The result is a butterfly-net of a novel, which is not so much disorienting as occasionally infuriating— much as one might grow impatient with the entangling aspects of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Emezi gives us both the phenomena and their organising geometries, and because a little goes a long way, a lot can make the writing feel over-seasoned.

What ultimately emerges from the cacophony is a tale about what happens when a chimeric soul is trapped in the confines of a human body. Ada’s self-harm reads as a way of perforating her restrictive human form, so that when we later see her undergo ‘reconfiguring’ via surgery, this too represents a freeing gesture, the peeling back of the skin to reveal the ripe self beneath.

Many of the reviews of Freshwater are seized by its radically unsettling narrative, and they try to evade self-arrest by paraphrasing the story into normalcy. There is something untoward in the way the story blooms onto the cover of one edition of the book (a faux pas as bad as a trailer that gives away the central plot of the film, and just as disruptive in its prescriptiveness), or the way each chapter is headed by a portentous epigraph (the literary equivalent of loudly announcing yourself before you enter a room). The cast of spirits who narrate the inevitability of Ada’s journey towards mental extremity have to display the otherness of their world in ways that teach us how to read them. Mostly they manage this rather well, but occasionally the prose elongates into great meretricious towers of description. Often a stunningly precise sentence will be followed by one whose meaning blurs under its own weight. Here is the spirit Asughara describing Ewan, one of the book’s major human characters, alongside Ada:

He didn’t seem real, from the thick richness of his voice and the weight of his rolled consonants to the things about his life that sounded as if they were pulled from the Frank McCourt memoirs she’d read as a child.

This reads inconsistently with how we have encountered Asughara before, and thus badly. Indeed, Freshwater often makes for strenuous work, asking us to take a great deal of interest in dysphoria and its operations, while lapsing into the writerly problem of telling rather than showing how Ada’s disparate selves experience the world. Here is one of the voices, sounding a little too much like John Cleese:

Forgive us, we sound scattered. We were ejaculated into an unexpected limbo—too in-between, too god, too human, too halfway spirit bastard. Deity seed, you know.

That rib-nudging ‘you know’—would the spirit-voice of a young Nigerian woman really sound like this? The management of voice is a shaky part of the critical scaffolding in a novel that is otherwise distinguished by its maturity. The missteps are only jarring because the story is otherwise so absorbing.

A final gripe, and not an insignificant one: reading this novel feels like submitting oneself to the dull clasp of the Big Book industry: there are chummy shouts from Taiye Selasi, NoViolet Bulawayo and Chinelo Okparanta on the dustjacket, and this strident cheering feels a bit like an algorithmic people who read this also bought endorsement. Freshwater doesn’t need training wheels: it is an accomplished novel whose fluidity and complexity will certainly mark it as one of the decade’s most intriguing works of fiction.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.