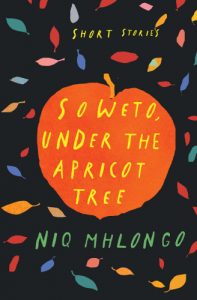

The JRB is proud to present new fiction from our City Editor, Niq Mhlongo, from his forthcoming short story collection, Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree, which will be published by Kwela Books in March. The excerpt is taken from the book’s title story.

Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree

Niq Mhlongo

Kwela Books, 2018

About the book:

“This apricot tree has multiple souls that fill me with wonder every morning and enchant me by afternoon. This tree has bitter-sweet memories, just like the fruit it bears.”

If the apricot trees of Soweto could talk, what stories would they tell? This short story collection provides an imaginative answer. Imbued with a vivid sense of place, it captures the vibrancy of the township and surrounds. Life and death are intertwined in these tales, which are told with Mhlongo’s satirical flair: funerals and the ancestors feature strongly; cemeteries are places to show off your new car and catch up on the latest gossip; characters come and go, like the politician who is mesmerised by his mistress’s manicure, the zama-zamas running businesses underground, the sangoma with a remedy for theft a private dancer in love and many others.

Take your seat under the apricot tree and listen to tales that entertain as much as they provoke.

Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree

After the unveiling of the tombstone, we are gathered at my home in Chi Town, Soweto. The apricot tree in the yard is beginning to shed its leaves as we approach autumn. The sun is shining brightly, and the tender yellowish leaves are rustling in the slight wind. My mother tells me that this tree is sacred and produces only one mysterious rotten apricot annually.

We are sitting in the shade of the tree and my mother looks happy. Her eyes are sparkling with unusual brilliance. Two of my uncles, Bhodloza and Sunday, are here as well. Uncle Bhodloza is wearing his black-rimmed glasses. When he laughs, he reveals his gap and a tooth that is stained brown. It’s amazing how clean clothes have transformed his lean body. I’m used to him wearing his favourite green overalls. Today he’s in the black trousers and a blue golf shirt that I gave him a couple of weeks ago. Recently, my mother warned him to stop wearing those overalls because he is unemployed and living at the Kliptown squatter camp. She told him that overalls are only worn at work, and that people who wear them while unemployed are confusing God. Uncle Sunday’s clothes, especially his shirts, are always sharply ironed, and today is no exception.

Other relatives and friends are scattered around our yard. They are drinking, smoking or eating. The noise is deafening because of the crowd and the Teenage Lovers’ song “Mayanka” on the giant speakers placed on the stoep. People have come to celebrate after the erection of my Uncle Tso’s tombstone at Avalon this morning. Uncle Tso was my mother’s brother who passed away a year ago. As is traditional, the family went to the Avalon Cemetery before sunrise to perform the necessary rituals and talk to our ancestors. A goat has been slaughtered, as well as a few chickens. Now it’s time for the feast, umqombothi drinking and stories. The smell of the stew cooking comes to my nose. My childhood friend Siya is here too, and we are sitting next to each other under the apricot tree. Ours is a special kind of friendship that doesn’t need conversation to sustain itself.

Nothing can induce our dog, Bruno, to stay in his kennel, despite the rags and an old blanket that have been piled up for his comfort by my mother. He paces around the yard for a while, then settles down on the stoep, not far from the speakers. He curls up to sleep with his nose tucked into his belly. Four pigeons settle on one of the top branches of the tree. A few leaves break off and carpet the reddish earth with their yellow and green. Next to my mother, Uncle Bhodloza is eating pap, chicken and goat meat. He has the habit of talking with food in his mouth, but surprisingly today he is simply concentrating on his colourful plate, which looks like a giant anthill. I can see the rainbow colours of the beetroot, pumpkin, cucumber, chakalaka, cabbage, rice, pap and meat. Because he is missing a few teeth he chews the meat with care. Each swallow is marked by the rise and fall of his plumsized Adam’s apple. Flies are buzzing around his plate. At the same time, my mother peers down the middle of a bone. She sucks it with her eyes shut, and stops only for a moment to say something. Her voice is full of pride and satisfaction.

“This apricot tree was planted in 1963. That’s what the apartheid government did when it moved black people into Soweto. They planted fruit trees for almost every matchbox house. A grapevine in front of the house. At the back they planted two fruit trees, a peach and an apricot tree, or a peach and plum tree. We were moved in with this apricot tree. Our peach tree died a few years ago. It used to be over there.” She indicates the spot with a nod of her head. Then she looks at me. “This apricot tree is as old as this Midway part of Chi Town, a year older than you, my son. This tree has witnessed lots of things.”

“But why did they plant fruit trees?” Siya asks, taking a sip from a can of Castle Lite.

“I don’t know. Maybe it was to fool us and make us believe that this place was better than where we used to live in Sophiatown, Western and elsewhere. But it was not only fruit trees that they planted. There were also a few tall bluegum trees.” She points with the bone at the front corner of the house. “We had one in the corner there in front of the house, next to the drainage system. You boys were already grown up when your late father cut it down, remember that, Sipho? Its roots were a problem to the floor inside the house, and the windows cracked all the time.”

I nod and she continues.

“Before these houses were built between 1962 and 1963 this place was a big farm called Albertville where people could buy livestock. Some people called it Albertine, but this was before it was given a Venda name, Tshiawelo, meaning ‘a place to rest’.”

My mother is seventy-seven years old, but to look at her you would never guess it. She is as sprightly as a woman at least ten years younger, with a moderately wrinkled but quite beautiful face and lovely brown eyes. Like any other black woman her age I know around this place, she has mastered the art of putting the past behind her. But today she racks her memory in an effort to recall, at all costs, the various experiences through which she has lived.

“Your umbilical cords, all five of them, shrivelled and fell off in this house. They are buried here,” she says, as if the falling-off was the true birth, the real beginning of the life she gave us.

Uncle Bhodloza drinks a glass of water after eating some raw green chillies. Beads of sweat cover his forehead. The water seems to cool him and help soothe the burning in his mouth. He picks up the last piece of meat and chews slowly. His eyes move from my mother to me with full appreciation of the food. The plate is so clean that it shines. The appetising smell of cooking wafts out to the tree from the open kitchen window.

My younger sister Thembi opens the door and comes out to collect the empty plates. She is still wearing an apron. She leaves the door open, and soon the smell of frying onions reaches my nose. But before she takes the empty plate from Uncle Sunday, he darts a glance at us and cleans the plate thoroughly with his bent forefinger. Bruno has woken up and comes to pick up a bone that my uncle has just thrown on the ground. He lies at Uncle Sunday’s feet and eats the bone. Uncle Sunday bends down and touches Bruno gently with his fingers. My mother chases Bruno away, and he removes himself to the gate where he sits penitently. His tongue hangs from his mouth. When more guests arrive, he walks in front of them as if guiding them into the yard.

Uncle Bhodloza is sitting on a beer crate with his back against the tree trunk, his whole attention concentrated on the umqombothi beer in front of him. A thought seems to strike him as he puts the big glass down. There is a dirty smudge on the glass where he has made contact. He scratches the right side of his greying head. The kitchen door opens again, and Thembi comes out to dish up more food for the people.

Uncle Bhodloza’s eyes turn to Siya. “You see that branch where the pigeons have just settled? That’s where your father committed suicide.” A shocked silence descends on us. We were not expecting him to talk about that past.

So sad