As part of our January Conversation Issue, Anietie Isong chats to Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike about his debut novel Radio Sunrise, which has been longlisted for the 9mobile Prize for Literature.

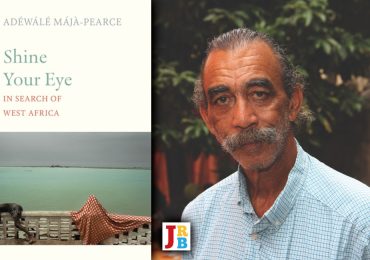

Radio Sunrise

Radio Sunrise

Anietie Isong

Jacaranda Books, 2017

Radio Sunrise tells the story of Ifiok, a conflicted journalist who often fumbles in his attempts to apply ethics to a profession where money exchanges hands frequently. His principles appear to be open to challenge, and it comes as little surprise when the reader finds him cheating on his girlfriend, thus bringing their relationship to an end.

Serious and funny by turns, the story presents a disquieting narrative of a post-military Nigeria hobbled by youth restiveness, oil capitalism and environmental degradation. Against this background, Isong immerses the reader in a libidinal world underpinned by greed, promiscuity and hypermasculinity.

Isong is a Nigerian writer, currently working in the field of public relations. He studied communications at the University of Ibadan and the University of Leicester, and has won several prizes for his writing, such as placing in the Olaudah Equiano Prize for Fiction and the Commonwealth Short Story Award. His debut novel, Radio Sunrise, was awarded an Author’s Foundation grant by the Society of Authors in the UK. The novel was shortlisted for the 2017 Kingston University Big Read, and has been longlisted for the 2018 edition of the pan-African debut writing award the 9mobile Prize for Literature (formerly the Etisalat Prize for Literature).

In this interview, Isong reflects on his writing practice, the literary representation of some of the themes, and the future of Nigerian literature.

Uchechukwu Umezurike for The JRB: Congratulations on having your first novel longlisted for the 9mobile Prize for Literature. I found it engaging and liked it for its humour, especially—something that is rare in Nigerian fiction. How did the story come about, and how long did it take you to write it?

Anietie Isong: Thank you, Uche. I started writing Radio Sunrise in 2010, and was offered a book deal by an award-winning independent press in Birmingham in the UK. Sadly, the press went bankrupt, and I abandoned the novel for years to focus on my career in public relations. I went back to the manuscript in 2016, and Jacaranda Books offered to publish it within twelve months. I have worked at a government-owned radio station in Lagos, so the novel is based mostly on my experiences there. All the things I witnessed, the various characters who worked there, and the office banter provided background for the novel. While I worked at the radio station, I occasionally wrote and produced radio drama, and this is where I learnt to infuse humour into my writing. With Radio Sunrise, I wanted to write a simple and easy-to-read comic novel, just like the radio drama I used to write and produce.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: Much of the literature from the Niger Delta engages with the theme of environmental destruction and social justice. While reading your novel, on the other hand, one feels that the Niger Delta serves mainly as backdrop; the grim sense of despoliation that afflicts the region is barely evoked in the narrative. Do you feel any ethical responsibility to point to injustice as a writer?

Anietie Isong: I feel strongly about the Niger Delta because I am from that region. But I am not obliged to write about the region in any particular way. So in my novel, although I mention issues of environmental destruction and social justice, I decided to focus more on family relationships in the region, in line with my objective of telling a simple, funny story.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: Certain literary critics have argued that contemporary African novels tend to be self-anthropologising. Eileen Julien calls such novels ‘extroverted African novels’ because they assume that their primary readers are non-Africans, are in the West. Sarah Brouillette, in fact, argues that much of twenty-first century African writing is ‘Western-facing—targeted primarily at British and American markets’. What might your take be on this?

Anietie Isong: My novel is deeply rooted in Nigeria. One might assume that since the novel is published by a UK press, the main target readers are Westerners. But we must also remember that there are a large number of Africans living in the UK. For instance, the people who attended my book launch at Waterstones in London were Westerners, Africans and Afro-Caribbeans, who all lived in London. So I think the readers of African novels published in the West are a lot more diverse now, and publishers must acknowledge that and design an appropriate marketing strategy.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: Your novel criticises the culture of ‘brown envelope’ (inducement, to be euphemistic), which has eroded the practice of investigative journalism. In fact, a character says, ‘Never cover an assignment without collecting a brown envelope.’ What do you think is at stake for a nation whose democracy is still flagging, when its watchdog is so compromised?

Anietie Isong: I first heard of the concept of ‘brown envelope’ in my journalism class, more than twenty years ago. Sadly, this unethical practice has not abated. Yes, the watchdog has been compromised, but the reality is journalists in Nigeria are so poorly remunerated that it is difficult to survive without inducement. There are media organisations who owe salaries for months. How is a journalist in such an organisation expected to survive? That said, ‘brown envelope’ is a reflection of the culture of soliciting and collecting money in Nigeria at all levels—from the security guard at the gate all the way to the ‘oga at the top’.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: There is a scene in the novel where you write about a corpse being kidnapped and its coffin stolen. It is perhaps the most bizarre detail in the novel, and I found it painted a rather cynical image of civil society.

Anietie Isong: That bizarre scene was actually a real-life story, and there was a time in the Niger Delta when kidnapping was so rampant that even the dead were not spared. In my state of origin, a preacher was kidnapped while he was giving a sermon in church. It shows just how far the country had disintegrated, and I wanted to show that in my novel, albeit in a satirical way.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: Are there plans to have your novel translated into other languages?

Anietie Isong: It would be great to translate Radio Sunrise into other languages, but I have left that task to my UK publisher.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: Can you say just a few words about the rising recognition of new Nigerian writing?

Anietie Isong: I think it is a good thing. But let’s not view this as something entirely new. Nigerians have always been writing, even during the dark days of the military. When I was studying at the University of Ibadan, I read many interesting works by many new writers then. And we had awards like the ANA/Cadbury Prize that recognised some of these talents. What 9mobile is doing for literature is wonderful, and I really wish that more corporate organisations would also sponsor awards, even at country level. In the UK, for instance, we have not one or two, but several awards for published fiction.

Uchechukwu Umezurike: May I ask what you are working on at the moment?

Anietie Isong: No, I am not working on anything new at the moment, as I have a demanding full time job. But if Radio Sunrise continues to be well received, I might consider a sequel. I am also considering an anthology of my short stories—I have written quite a few of these over the past fifteen years.

- Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike has had his short stories and poetry published online and in print magazines, and he has also won a couple of awards for his writing. He is a PhD student at the University of Alberta, Canada.