As part of our January Conversation Issue, Wamuwi Mbao chats to Chibundu Onuzo.

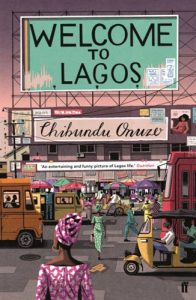

Welcome to Lagos

Welcome to Lagos

Chibundu Onuzo

Faber and Faber, 2017

The swish Cape Town hotel where I’m meant to meet Chibundu Onuzo seems a lifetime away from her latest work, the teeming Welcome to Lagos. Onuzo is part of a new generation of young African women whose writing is changing the face of African literature. When she appears (on the hour, as promised), she’s disarmingly understated for an author with two novels under her belt. She’s in town for the Open Book Festival, has been browsing at the markets and she’s planning to climb Table Mountain later in the week, but she’s agreed to sit down and chew the literary fat with me.

Naturally, I start by badgering her with a horrifying literary trope, asking her if she’s written The Great Lagos Novel. ‘I think it’s for readers to say if it is a Lagos novel, let alone if it’s great. I hope so! It’s definitely my attempt—I threw my hat in the ring.’ I tell her that my sense of Welcome to Lagos is that it’s infused with a strong sense of the city, which she accepts reticently.

Over the next hour, we discuss the writing craft, her sense of herself as an author, and what ‘home’ means when you’re a diasporic African.

Wamuwi Mbao for The JRB: I’m going to begin properly by throwing a quote at you. Joan Didion said that writing ‘involves the mortal humiliation of seeing one’s own words in print’. What did you think when you first saw your words in print?

Chibundu Onuzo: The first time was The Spider King’s Daughter, which is a while ago now—about five years. I found it all quite overwhelming. It was my final year of university and then suddenly this thing which had been on my screen for many years became real. The first time I had a hard copy it was the proof copy, and it was a real wow moment. But then when it came out, I became a Nigerian author. People would say ‘oh, there’s a Nigerian author—come and say something about the Nigerian elections’ and I had to say that my book is about two Nigerian teenagers and I’m not necessarily qualified to speak on these things!

Wamuwi Mbao: Why do you think that is—as soon as you’ve written a novel, people think that you’re an expert to be consulted on a wide range of issues?

Chibundu Onuzo: It’s partly pragmatism. In a British context, they get a lot of stick for not being diverse enough. So once a Black person gains prominence in any field, you’re automatically an expert.

Wamuwi Mbao: What’s the most random thing someone has asked you to comment on?

Chibundu Onuzo: The World Cup. I mean, I watch Nigerian football, but I have no idea what offside is …

Wamuwi Mbao: Neither do I.

Chibundu Onuzo: But I’m generally quite up for it. I was asked once to write about Madonna, after she’d adopted an African baby. [chuckles] Because I’m an African person, I generally have an opinion because we all have opinions on these things, but then the question is—do I necessarily want to share my opinions in public?

Wamuwi Mbao: Your writing is quite incisive in its focus on the overlap and contrast of experiences that proliferate in the city. In Welcome to Lagos, we see close attention paid to how people connect across and in spite of their differences.

Chibundu Onuzo: I started off with two characters, Chike and Yemi, and they were in the Niger Delta. I very quickly realised I didn’t know enough about the Niger Delta to set a novel there. And I was thinking, ‘Where will they go? Lagos!’ I know Lagos, so that’s what I wrote. I didn’t necessarily know they were going to end up in Lagos, but I always envisioned them picking up all these people along the way …

Wamuwi Mbao: Which is a fantastic conceit.

Chibundu Onuzo: Thank you. I read Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, which does something similar. I really wanted to write something with a large cast of characters. The problem was that at one point I had eighteen characters and the story had kind of lost all shape and momentum, so I had to kill some people off. So I ended up with seven. It was kind of like ‘survival of the fittest’. Welcome to Lagos is a bit of a cemetery, actually.

Wamuwi Mbao: That’s a wonderful way of describing it. How do you get a thought onto the page with the same impact that the real life carries? For example, you capture the feeling of a Lagos motor park without resorting to excess or journalistic description.

Chibundu Onuzo: I did a lot of research—sometimes Google isn’t enough. [laughs] I interviewed people who work with militants in the Niger Delta, people who worked for Shell … I interviewed a Nigerian soldier, which gave me a feel for what military life was like. For the BBC stuff, I knew two people who worked at the BBC so I just interviewed them. I wanted it to be authentic, even if I didn’t actually go to the Niger Delta.

The book wasn’t always called Welcome to Lagos. I grew up there, but we moved to England when I was fourteen. My sister came up with the title (which I initially thought was a bit obvious) because she thought the first title was boring. After I changed the title, I had to think about how much Lagos was in the book. I thought that if I was going to call it that, I had to really think about what aspects of Lagos were iconic to me—those extra details. So I think the novel expanded to fill the title, and I was moving through Lagos being hyper-aware. Lagos is home, but it’s also the place where I don’t have to explain myself. When you live in England, the moment you say ‘my name is Chibundu’, people are like ‘where are you from?’ In Nigeria, so much is known about you just by introducing yourself.

Wamuwi Mbao: Your first novel, The Spider King’s Daughter, was published when you were only twenty-one. What did you do differently when it came to Welcome to Lagos?

Chibundu Onuzo: Spider King’s Daughter wasn’t the first novel I wrote, but it was the first novel I completed. After that, I knew I could do it, and that was valuable. Welcome to Lagos took four or five years to write, but if the book lost momentum or I didn’t quite know how to work things out, I had that confidence that I would figure it out.

Wamuwi Mbao: And with these novels under your belt, do you have a favourite? That’s a bit of an unfair question, I know. The favourite is always the last one, isn’t it?

Chibundu Onuzo: The favourite is definitely always the last one. My favourite is the one I’m working on now. It’s the best thing since sliced bread—it’s going to knock everyone dead. I’m doing a PhD in history, and it’s going to be a historical text.

Wamuwi Mbao: How do you balance studying and novel-writing?

Chibundu Onuzo: I haven’t been that good at it. I’m in the fourth year of my PhD. Some people do it in three. I met someone who did it in two …

Wamuwi Mbao: That’s awful …

Chibundu Onuzo: Yeah. I try to do one thing at a time. So I write fiction for a week and I do PhD stuff for a week. I try not to leave the PhD work for too long.

Wamuwi Mbao: So what are you focusing on?

Chibundu Onuzo: I’m looking at a group called the West African Student Union, which was based in Camden Town. It was founded in 1925, for a very pragmatic reason: it was very difficult for Black people to find accommodation, or even to enter restaurants, at that time—

Wamuwi Mbao: ‘No Dogs, No Jews, No Blacks’?

Chibundu Onuzo: Exactly. So they created this space for themselves where there was food and a hostel. New arrivals could go there and stay until they found something more permanent. People like George Padmore ran study groups from there, and they began to really identify as the future leaders of West Africa. It was this idea of being in a place where you don’t have representation—who speaks for you?

Wamuwi Mbao: I think that would make a fantastic skeleton for a historical novel. Speaking of which, it’s a truism that most first novels are about the author themselves. Would we find you in either of your novels, if we knew where to look?

Chibundu Onuzo: Definitely not in Welcome to Lagos! [laughs] Maybe I’m a little bit like Isoken, although nothing like what happened to her has happened to me. I guess I see myself in the way the characters experience their lives in the city—what they see, especially.

Wamuwi Mbao: What are you reading at the moment?

Chibundu Onuzo: [laughs]

Wamuwi Mbao: What or whom?

Chibundu Onuzo: I’ve read a lot this year—it’s been a good year for African fiction. I read Rotten Row, Petina Gappah’s new collection. I’ve also read Stay with Me, by Ayòbámi Adébáyò. One that really struck me this year was Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table. It was very unusual: I haven’t read anything like it before. I’m also reading some stuff on my Kindle that’s really bad, but really good.

Wamuwi Mbao: Well, there’s a lot to be gained from bad literature. I’m a fan of reading something a bit different. If you only read the Pulitzer winners, you miss out on a lot.

Chibundu Onuzo: Yeah. [laughs] But I also have Kamila Shamsie’s new novel Home Fire lined up, so I’ll go back to more elevated levels soon.

Wamuwi Mbao: So, obviously I did my research on you. You’ve written quite a bit about cities and about the legacies of colonialism as it applies to cities. They feature prominently in your fiction—why do you think that is?

Chibundu Onuzo: About the city in general or about Lagos?

Wamuwi Mbao: About the city generally, but also Lagos itself.

Chibundu Onuzo: I’m a city person. Maybe the older I get, the more open I am to living away from the city. But when I came to England, I went to school in Winchester, which is about an hour out of London, and I hated it. It was nice, but I always remember spending my half-terms in London and going ‘Yes! People! A crowd!’ I like the buzz of it, the pace. The country is nice because it’s an escape from the city, but if there was no city to escape from … [laughs]

Wamuwi Mbao: So you’re like Virginia Woolf. You’d much rather be in the city.

Chibundu Onuzo: Yeah. Like today, for example, I’ve been walking around Cape Town. If I was in a rural area, obviously there’d be nature to walk in, but …

Wamuwi Mbao: Nature gets boring after a while?

Chibundu Onuzo: Exactly. Anyway, I haven’t seen that much. From a plane, it looks like any European city. But then as the plane gets closer to the ground, and you see the—do you call them shanties over here?

Wamuwi Mbao: The townships.

Chibundu Onuzo: And I think, ‘Yes, I’m still in Africa.’ And when we drove from the airport, I thought ‘This place looks like Lagos!’, and then you come here [looks around the hotel] and it’s just such a contrast. This isn’t my first time in South Africa, though: I’ve been to Joburg and Durban as well. What I noticed the first time, and what I find frustrating, is that, in Nigeria, the government doesn’t work—for anybody! If you’re rich, or if you’re poor, you don’t have running water! You don’t have constant electricity. In that sense, the government doesn’t discriminate—thank you rubbish government! [laughs]

Wamuwi Mbao: At least they’re an equal opportunity rubbish government.

Chibundu Onuzo: Whereas here, the government is capable of running infrastructure to some of the people, but at the expense of these other people. I saw the same thing in Brazil, where the favelas are in stark contrast to the luxury places.

Wamuwi Mbao: Finally, let’s take it back to the writing. What’s your writing routine? Are you one of those fabled authors who gets up at four in the morning and writes for three hours every day, or do you write as it comes to you?

Chibundu Onuzo: I write on my laptop when I have a stretch of time. I used to write at night and I used to be very precious about my time. From midnight to about four in the morning there’s a special quality of silence that you get, which you don’t get during the day even when you’re alone at home. It’s as quiet as death, with no cars, nobody coming to deliver the post. The problem is that your sleep pattern becomes different from the vast majority of the world’s—sleeping in the afternoon and being awake at night isn’t sustainable, so I’ve given up on that and I now make do with normal hours.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.