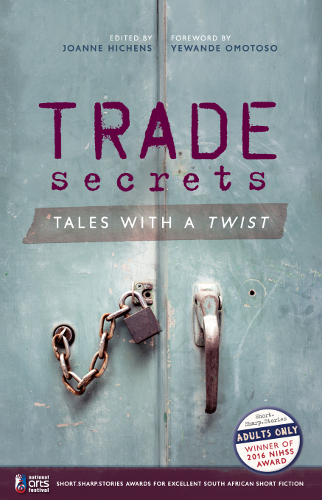

Exclusive to The JRB, new short fiction from Ntsika Gogwana, excerpted from Trade Secrets, the new Short Sharp Stories anthology. Gogwana’s story, ‘Home Cooked’, was a Commended entry in this year’s competition, with judge Phakama Mbonambi calling it a ‘powerful read’.

Home Cooked

Ntsika Gogwana

It was already late afternoon when she arrived from doing the shopping at the taxi rank. Nomafa anxiously arranged the ingredients for a simple chicken stew across the cupboard counter: four half-frozen pieces of chicken, an onion and two tomatoes. The stark but clean shack was clothed orange in the fading light. Soon, Sizwe would be arriving from the factory and she wanted him to arrive to a hot, freshly cooked meal—as always.

He worked twelve-hour shifts, Monday to Saturday, but he barely earned enough for them to survive. Yet still, Nomafa took pride in her daily efforts to make the most of whatever they had. Whether it was an extra buttonhole that needed to be sown into Unathi’s romper to make it last yet another infantine growth spurt or mending Sizwe’s overall trousers, all of it was done with care.

Being Sizwe’s wife had never been easy. But today had been particularly taxing—her neck and shoulders ached and although she had no appetite herself, she stood, chopping, slicing and stirring feverishly. As a pot of rice began simmering and the aroma of onions frying in chicken fat wafted through the shack, she cut her index finger on her left hand while slicing the tomatoes. She stopped cold as the acerbic juices pierced into the small wound. She staunched the blood, wrapping her finger with a small part of the floral apron secured around her fleshy belly. She fussed to the bedroom door to throw a tender glance over the plump boy-baby asleep in the cot, stood at the doorway, a strong hand still gripping the throbbing finger, as she admired the fruit of her womb.

Although there was no door to close off the bedroom it was cosier than the larger kitchen cum-living room. From a sun-burnt wedding photo on the dressing table, Sizwe and Nomafa smiled back at her enthusiastically, ignorant of the marital trials that she now knew too well. She roused herself from the multitude of thoughts beginning to run through her head and made her way back to the kitchen. The bleeding had stopped.

Back in the kitchen, she heard from under the window a hissy radio announce that it was nearly six o’clock before an anonymous male started his drone into the hourly news broadcast. Nomafa turned the stove off and settled herself into a chair, waiting for long-striding footsteps on the gravel and the familiar shadow to ghost past the window.

An eternal, silent hour passed as the heavens gradually blackened and crept over the little shack. The carefree sounds of children playing on the street and neighbours arriving from work slowly subsided, replaced by the rhythmic sirens of crickets and the intermittent punctuation of barking dogs. Outside, the window panes of neighbouring shacks darkened except for a streak in the near-distance reflecting the pale moonlight clouds. She drew the curtains closed, lit a solitary paraffin lamp and placed it at the centre of the table. The flame, trapped in its glass cage, cast a ring of gyrating forms on the walls, the forms heightened to a demented ferocity as the light was further distorted by the undulations of the corrugated iron. Nomafa began to wonder: was Sizwe lying bleeding in a wind-swept alley, had he been attacked, was there violence, was he dying a lonely death? Or more likely, was his head resting on a young, unmotherly breast? Each passing moment bore its own tremor of torment: fear, then jealousy, followed by longing.

She heard the tinkle of keys followed by the rough clattering of the lock turning. She stood up and offered herself up to him for yet another kiss-less embrace. She felt his stiffness. His jacket stank of stale tobacco smoke and the sickly scent of another woman’s perfume.

‘Hallo, s’thandwa,’ she said.

‘Hallo,’ he replied.

She walked to the stove, struck a match to ignite the gas rings under the pots, now burning blue, and placed two white plates on the counter. She switched off the radio then made her way back to the table. Sizwe slumped loosely on his chair, staring into some imagined distance, pretending not to be aware of Nomafa looking at him.

‘Long day at work, s’thandwa?’

‘Yes,’ he said tersely, still pointedly looking away from her. His breath carrying the sour smell of beer but he wasn’t drunk.

The yellow flame of the paraffin lamp flickered in quiet fanaticism between them, as if burning with a thousand unasked questions. She drank in his presence greedily, her eyes searching him for an explanation, some meaning to the long hours alone in the shack. She always knew that his eyes belonged to other people, other places where there was laughing, dancing and love. But receiving Sizwe at the dusk of each day still gave Nomafa a quantum of reassurance; it was a regular affirmation of her wifely dignity at the end of the daily monotonous meandering blur of dull domestic chores. This was her only time to be his only woman, her time to devote herself to his distant intense presence. For her, these sacred indulgences and well-practiced rituals of forgiveness were also her daily victory over his other life, the other women.

There was nothing remotely picturesque about Sizwe; his physical presence was imposing—a thick neck and stout chin, his voice direct and coarse—hard to believe he had once been capable of tenderness. His demeanor was as practical and without misdirection as the workman’s boots on his feet. Whatever he did, he did in a matter-of-fact, no-nonsense way, with no beauty nor sentiment. For instance, when they hammered together the shack for a marital home, an iron sheet slid off the roof and tore into Nomafa’s shin. Sizwe took command of the situation with sheer bloody-minded instinct; he bandaged her wound, sat her in the shade of the apricot tree and ordered her not to be stupid, leaving her to teeter between humility and humiliation. She remembered how she had once loved him for that, that is what husbands were for, she had thought then even as her wound thronged. A pathetic whimper called out from the dark bedroom. She got up and walked to the baby. As she re-emerged into the glow of the paraffin-lit room, hushing at the milk-warm bundle, Sizwe turned to her. His eyes, alert and bloodshot, speared her.

‘Do you want to eat supper?’ She asked, anxious to avoid his eyes. ‘You must be hungry.’

‘Not now. Maybe later,’ he replied.

‘It’s late and I’ve already reheated the pots. And you must eat after the long day you’ve had,’ she tenderly insisted.

His eyes drifted to the baby.

A cold shiver passed through her leaving a numb taste on her tongue. She waited for a reply, any subtle gesture of approval. Instead his eyes, protruding from their sockets as though they would jump right out of his head, remained fixed on their son.

‘Let me put Unathi down and I’ll get you some food.’

‘Ndithe hayi!‘ he said annoyed, defying her instinct to nourish with the abrupt disdain of a judge dismissing a shoddy line of reasoning.

Then he did something that shocked her. Without a further word, he stood up and sauntered out the door and into the night, leaving the door open for her to inspect the gaping darkness, and wonder if he meant to come back. Faint pangs of despair, now anger, rippled through Nomafa. She placed the baby high on her left-hand shoulder, picked up the paraffin lamp in her right hand and made her way to the bedroom.

‘He’ll be back,’ she muttered to Unathi, willing herself against the possibility that Sizwe might never return. What would become of her? How would she take care of Unathi alone? Quietly she put him down in the cot onto a quilted cotton spread she had made when she was still pregnant with him. She sat on the bed without stirring, watching his hands grab at the air. She thought about how Unathi’s facial features were growing to resemble Sizwe’s. His soft, round face was beginning to firm into his father’s robust proportions, even the gentle stare from his eyes was quickening to a familiar intensity! As she gazed at the scene a memory twisted in her gut as though a sharp forgotten fragment had lodged in her—the instant when Sizwe had struck her on the face in this very room. She remembered the naked shame of how she had cowered in front of him in shivering convulsions afterwards, sunk down to her knees, folded and frozen in primal defense, shielding the belly Unathi was at that time floating in.

She reached her hand into the wardrobe and curled her fingers around a small bottle neatly wrapped in newspaper. Her heart throbbed terribly.

How many times had she coaxed him to love her, to love their son, challenging him to come clean and give himself to her alone, to his small family. Each time her hints passing him by before he wandered off, a restless dog looking for yet another crotch to sniff. A brutal, disgust tumbled in her gut at the thought of the years she had kept this private space for him in her most secret heart—the place she had curated, gathering the infinite unutterable accumulation of agonies and torments of being Sizwe’s wife. Then, as though the festering abscess in her heart had suddenly burst and drained itself of emotion, everything seemed decided and beyond her personal sentiment. For an instant she sat luxuriating over her surrender to fate: the glooms and silent rages would end that night. All conscious objections now seemed incomprehensible, falling off her shoulders like dead leaves. She stood up and looked calmly at the sleeping Unathi, inspecting the easy rising and falling of his tiny breaths, the baby lost in sleep.

A fresh gust of wind rushed through the still open door, carrying the savoury odour of chicken and onions into the bedroom. Without thinking any further she slipped the white capped bottle into her apron pouch. She picked up the lamp, bolted the door shut and walked over to the stove.

Now everything was happening automatically as though fate itself was propelling her. Without putting down the lamp, she lifted the lid of the pot containing the chicken stew and watched the brown gravy bubbling around the ugly grey lumps of flesh. She stirred the simmering liquid mess once and then switched off the stove. As she stood over the pots she reassured herself: all she was guilty of was cooking for her husband while loyally waiting for him to return to her; all she had done thus far was nothing but the right and sensible duty of any respectable wife. From the ink black night the sound of familiar footsteps crunched and heaved in rhythm with the chime of beer bottles clinking in a plastic packet. The door flung open impatiently. Nomafa’s eyes met with Sizwe’s unceremonious frame emerging out of the night. He closed the door behind him, shot back the bolt and sat forward on a chair.

‘You can give me something to eat now,’ he demanded, as if criticising her for her earlier eagerness, twisting open a beer bottle.

‘Yes. Everything is hot for you,’ she answered, watching him raise the bottle to his lips, his throat funneling a long pour into his throat, streams of condensation running down the sides of the bottle because it was so cold.

She returned to the cupboard countertop for the plates. On each she rested a steaming heap of rice, planted two pieces of chicken on each one and added an inundation of thick gravy. She placed his plate on a silver tray, added a spoon and settled the arrangement in front of her husband; he managed a nod of begrudging acknowledgment, and then promptly, in quick succession, shoveled two spoonfuls into his mouth. She fetched the second plate for herself and took her place at the table. A place she had earned in breast milk and blood. Her rightful place, the place only a dutiful and loving wife can claim. She watched him pick up a piece of chicken, tear off his first bite of white flesh, before she lifted a first mouthful of rice and gravy to her lips to feed herself.

Except for the muffled munching and the grinding of teeth, they ate in silence. One bite steadily following another until both plates were cleared. Sizwe reclined deeper into the chair and released a satisfied belch, opened another beer, poured the frothy brew into himself. Nofama calmly collected the plates off the table, stopped briefly at the open bedroom door to survey the sleeping baby, before placing the plates in a plastic basin.

Nomafa made her way back to the table, her legs tired and heavy; she lowered herself into the chair. Her face inscrutably blank, her hands neatly clasped together on her lap, nothing to betray the thoughts threading through the forest of trepidation in her mind, quietly biding her time.

Just as a fleeting thought of abandoning the entire ridiculous undertaking crossed her mind, Sizwe belched loudly and tersely demanded: ‘Get me a glass for my beer.’

And then the words escaped from her mouth: ‘I’ve decided that one of us must die tonight.’

She paused, shocked at the indecent ease of the words flowing from her mouth.

At first Sizwe sat motionless as though he hadn’t heard a thing.

‘Uthini?‘ he asked, the only giveaway of emotion a tiny twitch of curiosity above his right eye.

‘The chicken stew,’ she continued calmly, ‘I poisoned it.’

He turned towards her so viciously, his eyes wild with confusion, that the beer bottle toppled off the table and hit the floor with a loud clatter but without breaking. He released a sneering laugh. ‘Mfazi ndini! Have you lost your mind? What are you talking about?’

She explained without hesitation: ‘I bought two bottles from a herbalist at the taxi rank earlier today, the poison and its antidote, and while you were out getting that very beer you are drinking, I added the poison to the stew.’

While she spoke, Sizwe sat absolutely still, his eyes growing wider with bewildered horror.

‘I have enough antidote for only one of us,’ she said, her matter-of-fact tone surprising even her, ‘and I think it’s only fair, since you think you know best, and you are the head of this family, that you choose who between us gets to have it. It makes absolutely no difference to me which one of us lives or dies.’ She paused, frightened by the sudden realisation that she too was at the edge of death.

His first instinct was to grab at her throat, throttle the life out of her pathetic existence and be done with her forever, right there and then. But he could not imagine any of this being true.

‘Uyaxoka mfazi! You are lying for the sake of it, out of sheer spiteful boredom, just to make a fool out of me,’ he said biting his lower lip in mild fury. ‘Supposing one of us did die, what benefit would come to the other selfish enough to take the cure? If I am so disgusting, why don’t you leave?’ he continued, skeptically cocking his head, his eyes betraying the first glint of fear she had ever seen in them. ‘Is this some morbid joke?’

‘I’m not lying,’ she said, looking at him with all the earnest conviction she could conjure. Her hand worked into and out of her apron pocket. She held the small bottle and placed it on the table square in front of him as if to refute his suspicions. ‘You don’t have much time to make your decision, I’m afraid. An hour at most, they said.’

‘Thixo wam! Why are you doing this? I have no money to leave you. This is insanity! And what of your son, would you have him grow up without a father … Or a mother?’ He asked in utter seriousness.

Nomafa leaned back into her chair, weighing up his words.

‘You treat me—our marriage, this family, as if it’s all an inconvenience. You are satisfied to accept a wife and a son to bear your name as a shelter for your pride but you don’t live in it. I cannot hold up this loveless shelter for you, I cannot share you with all the others … I would rather die!’ She paused for an instant, shrugged her shoulders in contempt and continued. ‘As I said, the choice is yours.’

A terrible silence followed. Tension coiling up inside him, Sizwe sat still, gazing at the bottle, then at her empty look of tired disinterest. She could see that she had successfully disturbed him. He shifted in his chair and then emptied the glass of beer down his throat in one swift movement. And then finally he grabbed the bottle, raised it to his nose, sniffed at it with curious circumspection.

‘Let me understand you clearly,’ he said at last, holding the bottle up to his face. ‘You say I must decide who between us drinks this and lives. If I drink it I live and raise our son. And if you drink it, I die. Am I right?’

‘Kunjalo kanye. But if you take too long to decide, we both die and the boy will have neither parent to raise him.’

Sizwe paused, a poisonous grin slowly curling from his lips revealing a sharp yellow canine. At that point, he shook the bottle vigorously, unscrewed the cap and without further pause effortlessly swallowed the oily contents. His face shrunk into a grimace from the bitterness and he shifted uneasily in his chair.

‘Sidenge ndini! Did you think I would let my life be stolen by your madness?’ Sizwe shouted before another scornful flourish of laughter left his twisted lips. ‘Before you die your woman’s death, listen to me. I married you with every intention to fulfill every just expectation toward you and I did not deceive you. There is no justice in death, no justice in dying for the sake of a woman’s madness, a woman who repays my love as if it were hatred! I am a man and when I die, I will die a man’s death! Rha! What kind of man would die willingly of poison?’

A gleam of outrage flashed briefly across Nomafa eyes. She thought to ask, ‘How do men die then?’ but before she could say anything an abrupt cry came from the bedroom; the commotion had woken the baby. Nomafa sat motionless, her eyes fastened onto the mocking smile still lingering on his face.

‘Whose responsibility is he now?’ she asked in a placid tone.

‘Tyhini le! You’re not dead yet and you are still his mother,’ he said reclining further in defiance, his expression unchanged, his breath however becoming faster.

‘My life lies in my own hands,’ she said, leaning forward to stand. ‘It always has.’

It wasn’t till she rose assuredly from her chair and walked unhurriedly toward the impatient wailing baby that he began to suspect that he had been tricked, although still not sure as to how or why. Something about her determined tranquility, the undisturbed air about her as she strode easily toward the bedroom door jolted Sizwe into a cold panic.

Just as Nomafa re-emerged from the bedroom gently cradling their son into her bosom, he stood up suddenly and stepped forward a pace, staring at her as though she had just struck him in the mouth. He stepped towards her again, now trembling and clutching at his stomach. He crashed violently onto the linoleum floor, his jaw clenched, stubbornly refusing to wince. He released a convulsive spasm of breath, his eyes fixed on his wife in frantic, demented shock. In full possession of her faculties, without the merest shaking, Nomafa walked over to him, baby on hip, and leaned over him, staring at her husband one last time, just as a grey veil closed over his eyes.

- Ntsika Gogwana was born in Mdantsane and educated at Unisa and the University of Fort Hare in Agricultural and Animal Sciences. He works as a Food and Beverage Chemistry Analyst and is interested in producing fiction that challenges normative gender and sexuality narratives. Follow him on Twitter.