Niq Mhlongo reveals what to see and do for the complete experience of Soweto.

Of all the entrance points into Soweto, my favourite is the Diepkloof Extension off-ramp from the N1 Highway. This is because it is near the mine dump that even some Sowetans mistake for a ‘little mountain’. For an informal tour guide like me, that mine dump is a very useful starting point when I introduce visitors to Soweto for the first time. It symbolises the unhappy birth and childhood of this great township, the site of the politics of poverty and segregation, moral darkness and spiritual emptiness, and the struggle for democracy in South Africa.

It’s ten o’clock on a Saturday morning and my friend Maki and I are on our way to Soweto. I have just picked her up at Park Station in downtown Joburg. The sky is a colourless vault, cool, high, and barren of the threat of rain. This is a good sign because I know we will be encountering the pleasant incessant loudness of Soweto’s streets. I’ve convinced Maki that Friday or Saturday nights are the best for nightclubbing in Soweto, because we’ll have the whole of Sunday to nurse a hangover, or attend church to seek forgiveness for sins recently committed, dancing to kwaito or house music on the stage at the new Ditsaleng Pub.

‘This is where Soweto begins,’ I point at the mansions of Diepkloof Extension opposite the mine dump.

We drive past slowly as Maki takes pictures of the houses. She is at the same time live-tweeting and Facebooking coverage of her very first visit. Our destination is the Orlando Towers, one of the most distinctive landmarks of Soweto. From our conversations on the phone I’ve learnt that she loves art, and I’m sure the graffiti on the cooling towers of the defunct power station will strike her as beautiful. I want her visit to start on this more serious, artistic note and end in my neighborhood of Chiawelo on a more jovial one.

‘How much do you think these houses are worth, especially that one?’ she points at the house that I knew, growing up, as Dr Irvin Khoza’s—the chairman of one of the biggest soccer clubs in South Africa, Orlando Pirates.

‘Five million, I guess,’ I answer. ‘Here in Soweto we call this area Diepkloof Expensive. It was originally meant for the rich black people, before they were allowed to live in the white suburbs during apartheid.’

Maki is from Hiroshima, Japan, and has been in South Africa for only about three months. She cannot believe this is the same Soweto she has heard about.

Crossing the road that separates Diepkloof Extension and Zone 5, we start seeing a lot more people along the road. The windows of the car are open, and from both sides comes a cacophony of kwaito and house music. I’ve been playing Ali Farka Touré’s ‘Amandrai’ in the car, which Maki says she has been enjoying since she lived in Accra for few years, but I switch the CD player off so that she can get a feel of the music outside, which I think represents the soul and spirit of the heart of Soweto’s youth.

There are lots of people at the Orlando Towers. The aroma of roasting meat from the braai stand by the entrance brings a faint pang of yearning to the top of my stomach. Maki asks me to take pictures of her with the towers in the background. We decide to take the lift to the top of the towers (R80 per person) for the 180-degree view of Soweto. Since I’m scared of heights, we agree to go to the Chaf Pozi bar and fortify ourselves with a dumpy of Castle Lite first. Without wasting much time we to go the tower lift, where we wait with two Afrikaner brothers from Benoni. One of them has brought his two young daughters along. The taller daughter is carrying a digital camera and she tells me she’s here to capture the moment her father conquers his acrophobia by bungee jumping off the top of the towers.

One hundred meters up, the towers offer a great view of Soweto. We’re allowed to spend about ten minutes at the top, and the lift can only descend once the two gentlemen have done their bungee fall. From the top, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital and the University of Johannesburg Soweto Campus look very close. To the east we can see the city of Johannesburg; the Soweto Theatre in the west. Also vividly visible on all sides are the mine dumps that surround Soweto. Unfortunately we cannot take pictures because our phones are locked up downstairs, but I’m able to give Maki a brief history of my township by pointing at the landmarks. To the south is Pimville, one of the oldest sections of Soweto, where my family lived before I was born in Chiawelo in 1973.

At the top of the towers, memories start to cross and re-cross my mind. My mother once told me a story about an experience she had in Soweto in the 1960s. She told me that the house that we now call home in Chiawelo didn’t have windows, doors, or a tiled floor when they occupied it in 1963. The grass inside was tall, and there were a lot of snakes in the area. Since my father earned very little, cleaning the Post Office, he had no money to buy the material to fix the floor. As a result, my mother and her friends would go to the nearest farm in Pimville to steal cow dung to make a floor. On one of these excursions my mother got bitten by the farmer’s dog. That scar of poverty is still engraved on her hand like an ugly tattoo.

Today the people of Soweto seem to have mastered the art of putting the past behind them. This feeling radiates from people’s faces as Maki and I visit the Hector Pieterson Memorial in Orlando West. Maki is surprised at the special attention she gets from car guards, tour guides and hawkers on the street. This is the kind of welcome that I take pride in as a resident of this township. There are a few people I recognise among the hawkers, who are trying to sell Maki some of their memorabilia, and their handshakes and smiles are honest enough for her to build a ready friendship on. The site of the museum is a very familiar one for me. It used to be our small taxi rank, where we caught the taxis to the city way before I went to Wits University in 1994. We spend about an hour and a half in the museum, and as we leave Maki’s eyes are sparkling with triumph as she tells me that the visit has given her a better understanding of the Struggle against apartheid.

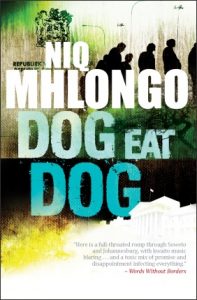

Our next stop is the famous Vilakazi Street, the only street in the world that’s home to two Nobel Peace Prize winners: Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. As we eat a buffet lunch at Sakhumzi Restaurant, my mind begins to race. Fragments of history that have been hidden in my memory for more than twelve years start to surface. I lived on this street for about fourteen years, and set my first novel, Dog Eat Dog, here. It was just an ordinary street then. I remember watching a Bafana Bafana game against Mauritius in 1993 at a friend’s house next to the restaurant where we are eating, the day after Chris Hani was killed in Boksburg. Today Vilakazi Street symbolises the story of Soweto’s economic, cultural and political richness, and it has a vibe that is fast catching up with Cape Town’s Long Street, Melville’s 7th Avenue and Durban’s Florida Road.

Our next stop is the famous Vilakazi Street, the only street in the world that’s home to two Nobel Peace Prize winners: Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. As we eat a buffet lunch at Sakhumzi Restaurant, my mind begins to race. Fragments of history that have been hidden in my memory for more than twelve years start to surface. I lived on this street for about fourteen years, and set my first novel, Dog Eat Dog, here. It was just an ordinary street then. I remember watching a Bafana Bafana game against Mauritius in 1993 at a friend’s house next to the restaurant where we are eating, the day after Chris Hani was killed in Boksburg. Today Vilakazi Street symbolises the story of Soweto’s economic, cultural and political richness, and it has a vibe that is fast catching up with Cape Town’s Long Street, Melville’s 7th Avenue and Durban’s Florida Road.

But being on Vilakazi Street does not in any way communicate the complete experience of Soweto. Every day this township is becoming more and more like a beautiful garden, nourishing its own people’s existence. To penetrate the inner reality of Soweto, you have to visit several more places. The Eyethu Lifestyle Centre in Mofolo—which hosted the inaugural Abantu Book Festival last December—E’Socialink in Doornkop and Bafokeng Corner in Phiri will give you an unforgettable experience. The Kasi Beer Garden at the Ubuntu Kraal in Orlando West is the location of South Africa’s only township microbrewery, which makes six variations of Soweto Gold Beer: 76 Jameson, Apple Ale, Cherry, Gogo’s Ginger, Orlando Stout and Superior Lager. For just R30 you can taste all six variations, and you can buy some as souvenirs.

A lone white cloud in the sky was chasing the afternoon sun, and in turn the sun chased the cloud as we arrived at the Credo Mutwa Cultural Village in Central Jabavu. A Soweto tour would be incomplete without setting foot here. Our guide, Lebo Sello, takes us on a tour of the cultural village that encompasses the history, culture, art, folklore and architecture of the people of Africa. We also climb the forty-nine steps of the Oppenheimer Tower for another panoramic view of Soweto. Unlike at the Soweto Towers, the view here is free of charge, although it conceals the truth of Soweto’s unhappy history.

The night is beginning to eliminate most of the township’s landscape when we reach our last stop, Ditsaleng Pub in Chiawelo. This is by far my most favourite place in Soweto. Besides it being close to my home, the space is big and clean, and there is plenty of parking. The security is great, and every kind of beer sells at R20 per bottle. Ditsaleng just opened in September, but it’s already busy. As we enter, the speakers are blaring house slow-jams, and even those of us who claim to subscribe only to the sound of Miles Davis’s trumpet can dance rhythmically.

As we leave later that night, Maki confides in me that today’s experience has been in accord with her most fervent desires and expectations.

‘The people of Soweto hate to be alone, they hate solitude,’ she muses as I drive her to the Vhavenda Hills Bed and Breakfast in Orlando West, where she has booked for the night. ‘They seem to arrange their lives so that it’s impossible for them to be lonely.’ I think she’s got it.

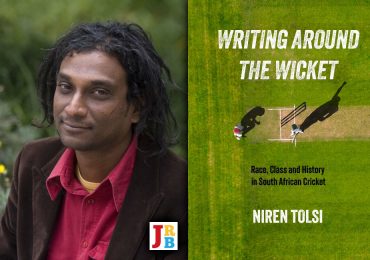

- Niq Mhlongo is City Editor; his latest book is an anthology of short stories, Affluenza. Follow him on Twitter.