When New York’s pout-fully punk weekly, The Village Voice, announced the end of its print issue last month, Gotham City went into paroxysms, and the world sunk into depressive nostalgia. Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo, one of the rag’s geeky collectors, recalls the first time he copped a print copy and revelled in its magic.

1.

What comes to your mind when you hear these three words: The Village Voice? It’s a terribly uncool question to ask, in fact, simply because its loyal cadre of readers, cheeky and edgy, ageing, permanently dissatisfied—just like the rag itself once was, gloriously—simply refer to it as ‘the Voice’. For me, a geeked-out, acned-out black boy, bookish to a fault, turned down by all the girls as a reading bore with no game in his genes, a ‘weirdo’ blerd (black nerd) before these things went vogue, with an inexplicable devotion to punk and rock zines (NME!, Long Live Nick Kent!, arrest Julie Burchill for her superior wit! Even if you gift Morrissey ol’ country England itself as a birthday gift, he’ll remain sulky as fuck!), little of what was left of my un-scattered mind went: whose village? Whose voice?

Ah. It’s a New York weekly, you fool. How can you love punk but … but what … is that piece of … it’s not remotely punk. Perhaps it was once. I don’t know. And me and a few black nerds I knew, mostly my village’s fellow goth-heads, somehow resolved the contradiction and swore to read everything that came our way. We thought sinking into punk and goth’s darknesses would shed a light into our frustrated extended teens, and never mind the surrounding African society that saw us as, by going goth, desperately trying to pass for white. Still, we—at least I—was not quite where it was at. I knew and could debate Brit-punk, pop, new wave, psychedelia, metal and all that with anyone … all the while, of course, on some days, immersing myself into the requisite hip ‘negro’ zines, Rap Pages and The Source, before Vibe Magazine and XXL, just to add a little bit of brown sugar into the bowl. But I still had no idea what the heaven The Village Voice was until about 1994.

Even so, I knew of its reputation, and that its insignia was a plain white inscription bedded in a block of blue backdrop. With the explosion of the internet, of course, it was one of the earliest publications I managed to get my e-paws on, impatient to devour everything in it. Some of the early issues, or performance sheets—for at its height and heart, each issue of the Voice was a Brechtian performative act—felt made up of all the city or indeed the world’s weirdest conglomeration of individuals. Their common oracular binding of article of faith being, For anti-ideological ideologues who revel in setting fire to ‘good values’, and readers and writers all too eager, too street, too alpha male, too gay, too, too, hip, beautiful, fucked up and double eager to bomb all those daring readers—and their mamas, papas, and rebel uncles, too—with annoying exuberance, and getting paid to do it, too.

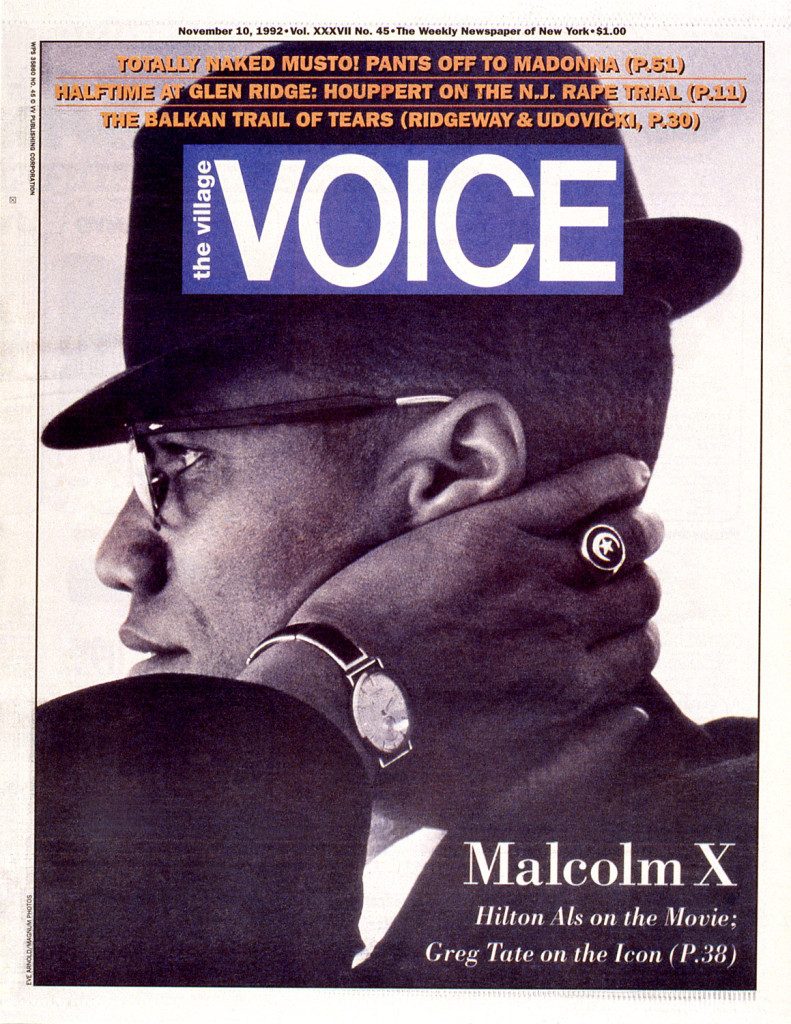

At least that’s how I first felt, reading, albeit digitally, the literary screeds from the rag. One of the earlier of these was the ‘double feature’ on Malcolm X—the man and the film—occasioned by Spike Lee’s biopic. Two of the Voice’s most literate writers—somewhat similar temper-mentally, but miles apart in style—Hilton Als and Greg Tate, weighed in. The cover itself was a thing of utter beauty. It tortured you with dreams and desires to touch, caress, clasp and file the actual printed cover, along with the entire issue in hard copy, somewhere precious. It featured a head-and-shoulder image of a sartorially elegant Malcolm, in a black suit, shot in side profile as though from the back right around his left cheek. The subject is presented in a state of relaxation and purpose: head thrust a little forward, although unthreateningly so, left hand adorned with a classic timepiece, pinkie finger accessorised with a black ring encrusted with the NOI (Nation of Islam) crescent star and a moon, geek spectacles framing the face; our dearly beloved and the embodiment of our love supreme, Brother Malcolm. The minimalist cover lines portrayed black elegance and spoke volumes of a kind of cultural transformation, quite like nothing since Cab Calloway gifted the zoot suit with his royal stamp of New African approval.

I would wait for weekly old-style URLs of the Voice’s content from friends. Back then, companies, including media companies, did not allow staff to use the internet for anything other than their assignments. (Sidebar: At this very moment, those same companies hire prepubescent staff to chase millions of internet-baked fans religiously ‘following’ the digi-age personalities called ‘influencers’. I can imagine in the not so distant future prospective employees uttering words like, ‘They say there used to be this thing, like, a type of news worker, called a “journalist”. Poor thing must have died from the burden of all that old technology.’)

2.

Time is a bitch. We grow and sulk. We grow and become our mothers and fathers. We begin to mouth off on all the middle class’s aspirational dross we found deadening not so long ago. The same applies to news-media products. The Village Voice is no more, Long Live the Voice! The paper’s owner, Peter Barbey, issued a statement saying it was ending its print operation in order to ‘revitalise’ the sixty-two-year-old paper through digitisation. But the Voice was one of the earlier cool kids on the digital publishing scene, which is how I first read it. So it’s not like it is upping its game. It is, in fact, becoming something it hated before: a commercial e-product, with no pretentions of altering social mores, or changing the lives of any awkward readers growing up on the wrong cultural trajectory. Defanged of its sleazy sexiness, The Village Voice as we knew it is dead.

Well, not quite. The world was shocked by the announcement that the petite, cheeky and unexpectedly erudite street corner seducer you were so used to seeing around your block is no more. A week after its owner decided to rebrand it as an online-only operation, the newspaper announced it would also lay off thirteen of its seventeen remaining union employees. Behold the callousness of the so-called digi-future. Lapsing into necessary nostalgia, John Leland and Sarah Maslin Nir assumed an elegiac tone in the New York Times:

Without it, if you are a New Yorker of a certain age, chances are you would have never found your first apartment. Never discovered your favorite punk band, spouted your first post-Structuralist jargon, bought that unfortunate futon sofa, discovered Sam Shepherd or charted the perfidies of New York’s elected officials.

Some of the major names associated with the Voice, including the ‘dean of rock criticism’, Robert Christgau, the jazz critic Nat Hentoff, and club and drag culture columnist Michael Musto—not to mention the likes of Greg Tate—either left, died or were scooted out of the weekly aeons ago. This is to say, perhaps the newspaper formerly known as The Village Voice was already dead, and the recent closure of the print edition just an acknowledgment that it could no longer do without those who made it what it became, a vital organ of the city, the country, and the world. ‘The print pages of The Village Voice’, continued Leland and Maslin Nir, ‘were a place to discover Jacques Derrida or phone sex services, to hone one’s antipathy to authority or gentrification, to score authoritative judgments about what was in the city’s jazz clubs or off Broadway theaters on a Wednesday night. In the latter part of the last century, before Sex and the City it was where many New Yorkers learned to be New Yorkers.’

The paper will cease its printing operations, and become full online platform. So far so … hell? Chin-up girls and guys, it’s only a publication. And ’sides, the entire world is living and preening on, online. But the Voice, the real Voice, isn’t dead. How do you remember the Voice? How did I first really fall in love with the print version of The Village Voice?

3.

It happened at the oracular hour of three am. It always happens at 3 a.m. with me. And perhaps for all other owls like me out there: The moment when something you’ve been anticipating for ages arrives. When it happens it either magically lifts you into that space where you too believe you can fly or crushes you altogether.

I first arrived in New York at 3 a.m., and it hit me with that smell only big cities have a right to … and this too is not entirely truthful. So, it’s not about big cities per se: it is about a particular smell you get accosted with at mostly train stations or bus stations. You know it too. If it had a colour, the smell would be a slimy green with goblet drops of miasmic greys, a lived-in and rejected smell that blankets mass transit spaces … Cape Town taxi rank, ol’ Pan Africa Taxi rank in Alexandra Township, Park Station in Johannesburg, Durban’s long-haul bus station, Gare de Noord and Gare d’Est at 3 a.m. in Paris—all have that smell. I carry it with me. All obsessive travellers with no millions of accrued air miles carry it with them, all the time.

It was at the beginning of American Summer when I boarded, ‘round midnight, a bus from the seedier parts of Washington, DC. I was hellbent on spending the rest of my money and year in the fabled New York City. I swear that particular bus service was operated by a clique of Chinese mafia. All in all there were only three passengers, myself included. But this is not a travel story, rather a prologue to how I first picked up the hard copy of The Village Voice newspaper in my hands and kissed it. I disembarked in China City, collected my travel bag, the Johnny Cash LP I’d been lugging around, and my courage and fear to step into the dense forest of urban nightmares and untold dreams that is New York, and looked around.

Winos all over the place, the grey slab concrete talking back at me, lights dancing on the ceiling of a corrupted sky. I walked around dazed. Amanda had promised to send me a car. You know those black Lincolns that snake around and through the yellow maze of the city’s cabs driven by PhD grads from Kashmir and Nigeria while chasing their big dreams? Ehe! Now. The car took its time. In fact it had arrived on time but, the dazed country bumpkin I am, I just could not locate it. So I did what I do best when in foreign spaces: broke into a stroll. It was not before long that I saw a bundle of Village Voice newspapers in a branded little cubicle. I bent down and picked up three copies. Looked back, only to catch the sight of a tall, bald man smiling and beckoning at me. Bow-n-goony, you are? the chap, Dwight we shall call him, asked. Yes Sir! Get into the car, baby. Your wife Amanda is worried sick about you.

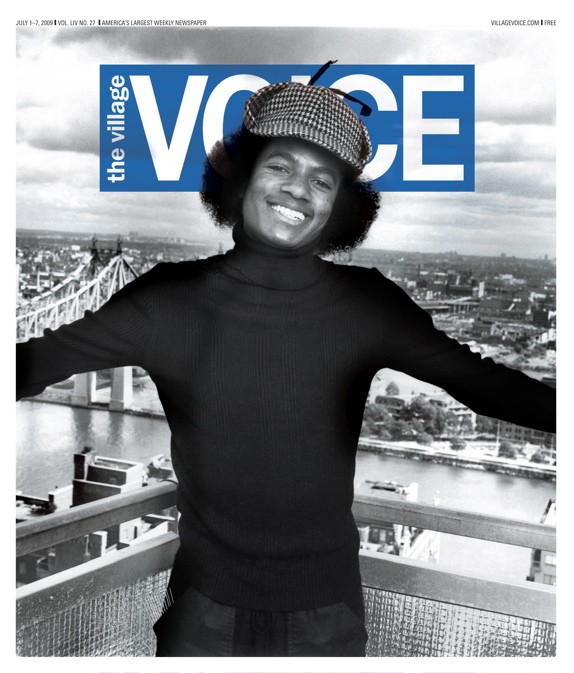

Dwight was an affable African American brother. I was too exhausted to tell him Amanda is not my wife. That she is my friend. An adorable, deeply caring friend: all she could do though at that Voudon hour was to send a car to pick me up at the appointed station and snore away in gentrifying Brooklyn. I was exhausted and elated, for in my possession were three copies of the fabled Village Voice. I clasped them hard to my chest and carried everything else with my right hand, as Dwight helped load my bags into the boot. There on the cover of my hard-copy Voice was a picture of black beauty like no other. A black and white photo of a black polo neck-clad and checked cap-wearing youngish lad named Michael Jackson, looking benign and grinning from ear to ear, and I remember the snappy cover line: ‘Man in The Mirror’.

The paper came out three or so days after the shocking announcement of the biggest-ever global pop star’s death. I’d first heard of it in DC while DJing for a rather sickeningly smart cluster-fuck of a frat group, comprising the international critics and curators who’d reached the end of our fellowship at the American University on Massachusetts Avenue, Tenleytown. When it happened we all proceeded to bust some moves, pretending to moonwalk or dance crazy crotch-grabbing steps, while some wiped tears and snorted, and everyone sweated whiskey:

Remember The Times

Do You. Do You, Do You,

Do You, Do Yo

Remember The TimesIn The Park, On The Beach

Remember The Times

You And Me In Spain

Remember The Times

What About, What About …Da ya, mhhh, ouuu ouuuh,

Do Yoooo?

Picture an image of drunk middle-aged visual arts intellectuals getting down like it’s 1999, or getting kite-high singing along to the lyrics of ‘Dirty Diana’. We all loved ourselves some ‘Dirty Diana’:

You’ll never Make Me Stay

So Take Your Weight Off Of Me

I Know Your Every Move

So Won’t You Just Let Me BeI’ve Been Here Times Before

But I Was Too Blind To See

That You Seduce Every Man

This Time You Won’t Seduce Me

It might not have happened in quite that way but I swear we all screamed ecstatically, almost with a sense of deranged catharsis when towards the end MJ screams in that vocal-like come-and death-entering helplessness: D-i-annnnnn!, sans the ‘a’: Oh, no: D-i-annnnn!

Nkosi yam’! Death, don’t ever imagine you’ve won. Cause you haven’t. We will remember the time. Just as I do now, reading the hard-copy of The Village Voice at about 5 a.m. in Brooklyn. All the obits and eulogies on our fallen Black Prince, our Peter Pan, out Injan Engine, our Blues maven in the age of Disneyfication, our man in the mirror, our brother and secret lover, our love supreme, our embarrassment in impolite company, our favourite Freak, our yesterdays, our pop-Charlie Chaplin, our James Brown reminder, our Dogon King reduced to a child-like dreamscape in a theme-park ranch with an impossibly intuitively meta-fictional name, Neverland, our greatest ever live performance hero who once reeked of untameable blackness and died looking like an Old White lady, perhaps Elizabeth Taylor’s alter-negro … yeah … the Voice’s issue that week was replete with magical writing and magical personal reminiscing about The King of Pop.

In this, our fictional time, in our age of social media’s super-saturated self curating, the word ‘magic’ has been all but been drained of its meaning. Magic Realism, Magical Life, Black Girl Magic, and so on, such that the upshot of it is that, indeed, the mundane has assumed, perhaps rightfully, a truly magical resonance, while what was once promisingly magical has become, well, you too can purchase magic over the counter. And so, although I too am a trafficker in word-magic, I know best to run when accosted with the term on the internet. And yet, magic does exist. In addition to Greg Tate’s—Greg Tate, again!—mystique-dipped cover essay on ‘Our Man in The Mirror’, with its chastising opening lament—

What Black American culture—musical and otherwise—lacks for now isn’t talent or ambition, but the unmistakable presence of some kind of spiritual genius.

—there was actually a shorter piece by the Brooklyn rapper, Abdullah Ibrahim’s daughter going by the name of Jean Grae, which reeked of magic. Entitled ‘In Defense of Michael Jackson’s Magic’, Grae’s tearful piece commenced:

A year ago, I tried to convince a stranger that, yes, magic does indeed exist. I wasn’t talking about David Blaine, Criss Angel, or street magic—no. I meant the magic in creativity, in manifesting things at will, in … in … aggg! I was so frustrated that I couldn’t explain to her, but then I realized that she would never, just believe, and wouldn’t even attempt to understand it. It made me so sad for her, to be missing out on the beauty in the world around her.

Down the line and growing ever more frustrated, Grae pleaded, choking with tears I imagined, writing in the Voice:

What could it be in a human that doesn’t recognise, or can so easily dismiss, clear and announced magic incarnate? Even if there is something in you, your soul, your fibre, that is impervious to it—how can you deny the existence if it affects the rest of the world on a deeply profound level?

And she retches up:

I cried man. I cried HARD, I cried just remembering the feeling of reading the first online headlines, waking my boyfriend to tell him the news. I cried harder because I saw his own tears well up.

The idea here is not to plagiarise Grae’s tears droplet by droplet, not to appropriate her swampful grief lock, stock and heave, but I remember my hands trembling at 198 bpm reading the following passage:

I believe in magic so much that, so much that I rely on it to live. I know that I’m capable of creating it, but I bow in the presence of those who are way more powerful than I. I also believe in the fragility of the human soul. I think there’s only so much battering and shielding it can take. I think there’s always a place in us that escapes and flies freely, even if you, yourself, are prevented from doing so.

At which point I must have woken Amanda with my morning soliloquy. Yes! I too know that place, Jean. Several of them. Raised by a squad of beautiful and feisty grannies, storytellers all, there’s just no not knowing a place made of magic.

I know when magic hits you in the gut and dares you to call its name. I can say without a whiff of embarrassment that at its height, and over decades, the Voice has affected the world’s ways of seeing and hearing in a manner too profound to warrant proof. I remember the stories about writers whose escapades within the paper’s offices often read like episodic snatches of Broadway boho-drama. Writers such as Ellen Willis, Stanley Crouch, Barry Michael Cooper, Colson Whitehead, Lisa Jones, Erica Kennedy, Joan Morgan, Michelle Wallace, Nelson George, Michael Musto, Greil Marcus, Richard Goldstein, and so on … to read their performative pieces of reportage was to bear witness to a city and country making and constantly remaking itself.

Working for an alternative, just like working for Drum magazine in its ‘golden period’ of the fifties and sixties, was surely not as uber-cool as some of us peering and dreaming from the outside might have imagined. Surely it was not all that rock and roll. Surely envy, ego and greed, as well as office romance, constantly threatened to sink the ship. As they should in a sane world. I do not know for a fact. But I’m not keen on perfect, fabled and dolled-up one dimensionality in culture. I’m as much averse to sipping the mainstream’s Kool-Aid as I am of imbibing scripture. Real life should be messy. It is quite possible that its height, or during its darkest hour, or both, the Voice was a cesspit of vice. So I’d love to imagine. Whatever might have happened or not, looking now at the roster of its writers, it’s clear they were its bedrock. They were its starchitects. Because of them, writing by the column inch—of which they knew there were only so many—there will never be anything quite like it. There will never be anything ballsy enough to make the experimental the norm, to talk and write about fantastical personages like Michael Jackson with so much humility and humanity. Nothing will replace holding the Voice in its compact, dense, rectangular form, with its shamanic essays shot through with sleazed-up smalls. Not that the web publication will be averse to attempting such trivialities as touching the reader’s soul. But it won’t.

- Bongani Madondo is Contributing Editor. His collection of essays, Sigh, the Beloved Country, was recently shortlisted for the UJ Prize for English Writing, Main Prize. He writes on music, photography, poetry, and politics.

3 thoughts on “A stranger in ‘the Village’: Bongani Madondo remembers the magic of The Village Voice in print”