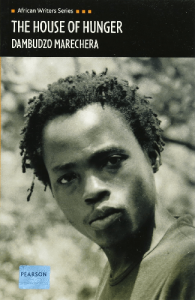

The House of Hunger

Dambudzo Marechera

First published Pantheon Books 1978; this edition Heinemann African Writers Series 2009

We knew that before us lay another vast emptiness whose appetite for things was at best wolfish. Life stretched out like a series of hunger-scoured hovels stretching endlessly towards the horizon.

—Dambudzo Marechera, ‘The House of Hunger’

1.

Zimbabwe has become a mythical country. Everyone has a story about it, and a seemingly unbelievable one at that. No sea monsters be there, but people talk about money that is printed on only one side, which Zimbabweans in Joburg sell to tourists as souvenirs. Apparently, there’s nothing on the shelves in Zimbabwe: the shops are small void museums of disappointment. It is said that in Dubai airport you can hear wealthy women chatting in Shona about the Zim diamonds they are taking to sell in China. There are the ‘Whenwes’, who still call the country Rhodesia or—perhaps worse—rhyme the last syllable of its name with ‘twee’. Still very rich, inherently sunburnt, but now living in South Africa, bitter about ‘When we used to have a string of horses in Bulawayo’, ‘When we used to farm hectares of tobacco, that we started smoking at 13’, ‘When we saw our names and our farm one day in the paper.’

I wanted to find Zimbabwe’s own story of itself—which is also its own story of being, at one point, (Southern) Rhodesia. I could easily have chosen any of their great living writers—Petina Gappah, Brian Chikwava, Tendai Huchu, Tsitsi Dangarembga, NoViolet Bulawayo—but I thought I’d choose someone long dead, who wasn’t Doris Lessing. They say dead men tell no lies.

‘The House of Hunger’ is the lead novella in Dambudzo Marechera’s collection of the same name. Today, however, the book may well have been published as one novel: all lobes of the same troubled yet fantastic mind. The twin demons of thirst and hunger shapeshift and taunt the characters in each story. And the narrator, ‘the educated lunatic’ (as he is sometimes called), crippled by his personal hamartia—a brand of self-loathing that poisons the well of his spirit as well as his relationships—provides a form of continuity, albeit an uneasy one.

‘The House of Hunger’ is the lead novella in Dambudzo Marechera’s collection of the same name. Today, however, the book may well have been published as one novel: all lobes of the same troubled yet fantastic mind. The twin demons of thirst and hunger shapeshift and taunt the characters in each story. And the narrator, ‘the educated lunatic’ (as he is sometimes called), crippled by his personal hamartia—a brand of self-loathing that poisons the well of his spirit as well as his relationships—provides a form of continuity, albeit an uneasy one.

The House of Hunger (the entire book) unfolds as a brutal, bloody, waking hell, superbly written and hyperreal. At every turn there are black Zimbabweans squashed into stains of themselves, the glares of ‘Whites Only’ signs, cracking bones, riotous protests and violent deaths. The sex is filthy, rarely consensual, and short, and the slums are closely-packed pain:

It was the House of Hunger that first made me discontented with things. I knew my father only as the character who occasionally screwed mother and who paid the rent, beat me up, and was cuckolded on the sly by various persons.

Soon-to-be cabinet ministers (once liberation comes) wait in exile in London perfecting their ineffectiveness. The rogue prime minister Ian Smith’s spectre looms; the oppressive colonial architecture closes in; and Fanonian cautions lurk.

The stories read as a swift sequence of incestuous nightmares with a recurring cast of interchangeable ex-private school chaps (à la Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster), with whom our lunatic drinks heavily and sympathetically despairs, in both Zimbabwe and the UK. ‘The Slow Sound of His Feet’ is like being dragged through someone else’s PTSD; the same can be said for ‘Thought Tracks in the Snow’.

Then there are the women. At first it seems as though Marechera treats them incredibly badly. When they are not raped, they are beaten; when they are not a pregnant nuisance, they are insufferably carrying a venereal disease, or are snobbish ice queens, as in ‘Black Skin What Mask’:

The black girls in Oxford—whether African, West Indian or American—despised those of us who came from Rhodesia. After all, we still haven’t won our independence.

But our main man, the lunatic, also shows a nuanced awareness of the performance of gender and the unique pressures of being a black woman progressive for his time. He also has a kind of sex positive reverence for sex workers, many of whom are his friends.

2.

This is a book of desire denied, of what the pain of that impotence drives people to do, and how it makes them unwilling contortionists and even co-conspirators in their oppression. From ‘The Transformation of Harry’:

And there we all were; in an uncertain country, ourselves uncertain. A land with a sly heart; and ourselves ready to be deceived.

For if colonialism was any one thing it was denial: denial of land, denial of African culture, denial of any form of psychic nourishment—including hope—denial of black existence itself. And neocolonialism is the denial that any of that is still happening.

First published in 1978, The House of Hunger speaks, or rather shouts forward from its own time to today. Perhaps the most painful parts of the book to read are those that show how little has changed. There are still young people basking in the intellectual wealth of Black Consciousness texts, only to look up from the page and survey the financial insolvency that marks their lives. In ‘The Sound of Snapping Wires’, cold and confused Africans in foreign countries wander, wondering what it’s all for:

‘His own ambition—what had it been so long ago in high school and then at university? What was it? It had started in Africa now it found him here in London.’

3.

By all accounts the book was a cautionary tale that wasn’t widely read. James Currey, publisher of the African Writers Series, in his account of the rollercoaster experience of publishing Marechera, mentions that when the author returned to Zimbabwe in 1982, Zimbabwe Publishing House (ZPH) took over his titles. Royalties were meagre as they didn’t sell well. And he often took copies from ZPH to sell in bars.

But it isn’t all darkness. Marechera exposes a hunger in his people that is sometimes used for goodness, that can express itself as ambition and be seen as a source of hope for the future. After you make it across each harrowing juncture, his wit and sarcasm appear, tempering the pessimism and bloodiness of it all. The banter whips between characters like a live wire. All the ugliness split open in The House of Hunger shows Marechera to be every bit the erudite, daring and talented writer he is reputed to be. Such beauty and a deftness with language ripples through the narrative:

And outside wet snow piled up softly like things which a man has chosen to forget …

—‘Thought-Tracks In The Snow’It had been, in the train, crowded and hot and dozy and how they talked endlessly of the soul of the country, how painful and lovely and boring it all was, hurtling on into God’s shadow.

—‘Burning In The Rain’

The House of Hunger may not be the story of Zimbabwe, the song of itself. Perhaps there is too much of Marechera in it for it to reflect anything but his enfant terrible legend. Indeed, significant events in the life of ‘the educated lunatic’ mirror those of Marechera’s neatly and tragically. It was said in the wake of his death that ‘he wrote as he lived and lived as he wrote’. But it certainly is a big story, essential reading, grander than one man. A story of a people still hungry, of painful memories and clues about the complex Zimbabwe that exists today.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing Editor Efemia Chela on the best fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the first article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.

Index

Authors

- NoViolet Bulawayo, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Brian Chikwava, Petina Gappah, Tendai Huchu, Doris Lessing

Books

- African Writers Series

Organisations

- Zimbabwe Publishing House

Places

- London, Oxford, Southern Rhodesia

People

- James Currey

- Ian Smith

Topics

- Black Consciousness, Colonialism, Fanonism, Neo-colonialism, modern privation

One thought on “[Temporary Sojourner] How little has changed in thirty-nine years: Efemia Chela reads Dambudzo Marechera’s The House of Hunger”