The Paris Review Interviews, a series of conversations with great writers on their art ranging from the 1950s to the present day, count as one of world literature’s signal landmarks. They’re all available to read for free, online at theparisreview.org. For the launch issue of The Johannesburg Review of Books, we thought it would be appropriate to talk to someone familiar with the art of fiction, and the art of the literary review generally, and so turned to our Editorial Advisory Panel member Philip Gourevitch, who is an author and long-time staff writer at The New Yorker, and who was editor of The Paris Review from 2005 to 2010.

The JRB: Let’s jump right in. This interview is meant to discuss ‘the art of the literary review’—as in, the type of publication dedicated to featuring and reviewing literature. What makes for a great literary review, in your opinion? What are the factors that will help publications like The Johannesburg Review of Books Enjoy a long lifespan?

Philip Gourevitch: There are many. I think that, as a rule, the great literary journals often arise from a particular moment and place, where there is an opening in the literary world that may or may not be aware of itself as such beforehand. Often they are started by young people who are breaking into writing about books and literature and ideas, the cultural and political life of their time and place, and their world—and they decide, ‘Why should we wait for the current gatekeepers, with their current frameworks, to make room for us? Let’s start our own magazine.’ Such magazines often have the feeling of a club, a group of friends, or of like-minded people as they start out—whether it’s The Partisan Review in the nineteen-thirties, or The Dial back in the eighteen-forties, or The New York Review of Books, which saw the opportunity to launch during a newspaper strike in New York in the sixties, and which really was a group of editors and writers who were very close friends already, calling on their friends to write and contribute. Obviously such a magazine also requires editors with a strong sense of their moment, who recognise that there is an opening for their authors to reshape the larger conversations about the culture in a way that people may not realise they’re missing or looking for, but will recognise once they get it.

One of the things that often happens in exciting magazines is that you start to have a core of writers. Sometimes these will be staff writers, some will be freelancers, but usually you end up—especially when your focus is on criticism, book reviewing and essay writing—with a half-dozen writers at any given time, who really define a magazine. This core group may change over the life of a magazine such that when readers say, ‘Oh, so-and-so are the people I read it for,’ every five to ten years that so-and-so is different. But there are always these regulars, as well as the occasional surprises.

And if reviewing is at the core of the magazine, the matching of reviewer and reviewee is critical: pairing subject and author in ways that are not just exciting, but sometimes also surprising, unexpected, so you have people saying, ‘Oh, there’s so-and-so writing about something unusual—I’m dying to hear what they have to say about that.’

The JRB: That makes a lot of sense. You’ve mentioned The New York Review of Books and you told us that you recently attended the memorial service for the great Bob Silvers, who edited it for over fifty years. He clearly got a lot of things right during his tenure. You mentioned in an email some of the things that stand out for you in terms of his style and management, but is there anything else you think he did particularly well?

Philip Gourevitch: For one thing he understood the idea of a ‘review of books’ fairly loosely, so that there were always, of course, book reviews—but quite often the longer review-essays digested quite a number of books, not just a single book under review. As a result, the pieces belonged as much or more to their authors than to the authors under review. So you might get something like, ‘Here are six novels that deal with private eyes in African capitals,’ and three of them might not be very good, but you don’t have to dwell on them because you can instead go off on the idea of the type of novel, and what’s new about doing it in these cities, and here are the two that I think are terrific—and you then have something much larger. [Editor’s note: in a happy coincidence, Leye Adenle’s crime novel Easy Motion Tourist, which features a private eye, of sorts, working in Lagos, is reviewed elsewhere in this issue.]

And also you use a literary review to publish reportage, and dispatches, and cultural commentary that may not be attached to reviews. Reviews are the core of it, but many of the more remarkable pieces won’t be reviews. Much of VS Naipaul’s and Joan Didion’s reporting appeared in the New York Review with no connection to any book, and those pieces might just as well have appeared in Granta, which doesn’t review books at all, or in The New Yorker. So the New York Review had a surprisingly flexible idea of what it was up to, except insofar as it was always a writers’ publication. Bob and his partner for most of the Review’s history, Barbara Epstein, never worried much about who the readers were, because they were confident that if they were getting the best work they could out of the writers they most admired, on subjects they thought most interesting, the readers would come.

The JRB: A literary review is one thing, but what about an actual book review? You’ve had a lot of experience with that—is there anything about a good book review that makes your heart pound a little faster? Is there anything you look out for?

Philip Gourevitch: For sure. There are times when you feel that the engagement of the reviewer’s intelligence with that of the author under review—either the meshing of minds, or the clash—brings a lot out about the underlying book. And, assuming that when you’re reading a book review you generally haven’t yet read the book, a very good book review can make you feel both quite excited about the book, and also like maybe you now don’t have to read it. An artful book review can distill a book’s essence that way.

In fact, I often find that I’m most interested in reviews of books that I have no intention of reading. An outstandingly knowledgeable person explaining something you don’t know much about, something off your normal reading radar, can be especially rewarding. And you’re much more likely to read such pieces if they’re part of a lively mix: you know, you came for the political debate but you stayed for the meditation on landscape gardening—and you wouldn’t have discovered that gardening piece if you didn’t trust the publication for its pieces on the subjects you do know best.

The JRB: You mention trust. It’s actually that intangible thing that makes you read a review, isn’t it? It’s the fact that you trust the publication. And one of the ways that you build up trust—one of the ways that you, personally, built up trust when you were at The Paris Review, for example—was that you published a lot of new writers of great promise, including the South African writers Damon Galgut and Alistair Morgan. How can you tell when a writer has promise? How do you spot a future star?

Philip Gourevitch: I hardly had to spot Damon Galgut. The way I came across him was he had been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for his novel The Good Doctor, a really great book. And I happened to be in London and it was in the front of a bookstore. I hadn’t heard of him. I started reading a page or two and I just carried it up to the register. I wanted to keep going. But he wasn’t being published in the USA very visibly at that point, so when I started at The Paris Review he was one of the writers I had in mind as embodying what I was looking for: a fine formal writer, who is original—I haven’t heard anything that sounds or feels like him—and whose material, whose concerns, whose world, is deep and engrossing to me. So I got in touch with him, and he was wandering somewhere as he likes to do, and eventually he got back to me, saying—I have these stories that are odd and I’m sure are too long, and he gave me all the different reasons that he was sure I wouldn’t be interested. And they were really fantastic. They were the three stories that were in his mind already as a book, In a Strange Room. And so we were able to publish two of those with him, ‘The Follower’ and ‘The Guardian’. And with Alastair, it was Damon who sent me one of his stories, because one of the ways you find writers is—writers know writers, talent knows talent.

But, you know, to touch more broadly on this subject of trust, I’ve noticed over my years as a reporter that I meet quite a few people who say, ‘Oh, I love reading the New York Times, except that the guy who is a specialist in my field is an idiot. You know—but the rest is terrific!’ It makes me laugh. If the thing you know best, you distrust, why do you trust that all the rest that you don’t know about is authoritative?

Maintaining trust is one of the reasons that some American magazines, notably The New Yorker, have an intensive fact-checking process. It can come across as neurotic, and is often mocked—many French writers, for instance, consider it an absurd exercise. But, if you’re reading an article, and you catch some minor factual error—a number is wrong, something that’s north of town suddenly gets described as south of town—even if you have no reason to think you’re dealing with intentional malicious deception, you distrust it. So the fact remains that the best way to build trust is to be trustworthy.

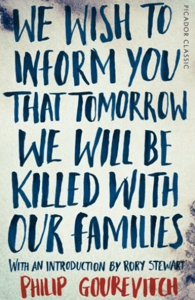

The JRB: And that’s what you yourself are particularly known for, that extreme diligence, which was very much evident, for example, in your best-known book, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, which is on the Rwandan genocide. We’ve just discussed a couple of African writers, and coming back to Africa for a bit, what other ways have you experienced the continent?

The JRB: And that’s what you yourself are particularly known for, that extreme diligence, which was very much evident, for example, in your best-known book, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, which is on the Rwandan genocide. We’ve just discussed a couple of African writers, and coming back to Africa for a bit, what other ways have you experienced the continent?

Philip Gourevitch: I’ve traveled around a bit, reporting—but I really don’t think of myself as an Africa hand, and I’m always a little wary, as I think many people are, of speaking generally about Africa on the strength of having been immersed in a very small country, Rwanda, over the years. Obviously a number of issues there are also in play in other countries in the region or more broadly on the continent. But to the extent that I feel any connection to parts of Africa where I haven’t spent much time, that connection has arisen from reading. Now I’m going to start drawing all sorts of blanks, but I remember in my late teens and twenties reading writers like Sony Labou Tansi, a novelist whom I found absolutely fascinating, and reading Achebe, Soyinka—and some of other Nigerian novels, like Sozaboy, and The Palm-Wine Drinkard—and reading in South African literature of course. I think one of the great works of non-fiction in the last century is Rian Malan’s book My Traitor’s Heart. I have also really enjoyed Zakes Mda.

I often have to stare at my bookshelf to remember books I’ve read but am not thinking about. I’ve sort of outsourced my memory to my shelves the way we do with our phones, and the books are not organised geographically—they can’t really be called organised at all.

Interestingly, Rwanda, when I first got there, was not a country known for its writers, though there are a few now starting to emerge. There have been a couple of powerful memoirs of the genocide. And, it’s not translated into English yet but the young Franco-Rwandan hip hop artist Gaël Faye wrote the novel Petit Pays, which got a lot of attention last year.

The JRB: Let’s talk a little bit about The Paris Review, which has a legendary slush pile—we don’t know if it does anymore, but according to tradition everything submitted is read at least twice, and there was a very rigorous process for determining what was going to go in. How important was that slush pile in ensuring that the magazine kept publishing the best stories by the best new voices?

Philip Gourevitch: The Paris Review is distinct from some of the other reviews we’ve been discussing in that, from the very beginning, it had one rule, which was, ‘We will not publish literary reviews.’ Not because they’re of no interest, but because a lot of publications are already doing that and what we really want to do is focus on the people who are producing it, give them a platform, especially new voices. And then The Paris Review Interview was invented, in a sense, as a way of having a way to talk about books and writing that was new and that wasn’t being done elsewhere. And so you had a combination of the new writing that was running through the magazine and the great masters reflecting on and discussing specifically their craft and their understanding of how they went about what they did, which is one of the greatest tutorials on writing out there, simply to read the complete Paris Review Interviews.

The slush pile consists basically of all the unsolicited manuscripts that come in directly from writers—no agents. As a rule, these are not very well known writers. We’d get bags full of them, and yes, we had a rule that everything had to be read twice—that is by two different readers—to give everything a fair shake at being noticed. Obviously most of it gets sent right back where it came from, but we published at least one story a year that came in through the slush pile. That may sound like an enormous amount of effort for not much, but in fact those are some of the most exciting things to publish. You’re essentially giving a person, a writer, a kind of stepping stone that it can take years for the writer to find. Some writers whose first or second stories we published—within a few years later they were publishing books and getting much broader recognition for their work, and that was thrilling. And we also did that with translation. With the great Chinese writer Liao Yiwu, who’d been in jail a great deal of the time since Tiananmen Square, we were the first to publish him in English, and he went on to publish a number of books in America to wide acclaim.

So part of what we were training younger editors in is the understanding that, although you’re going to reject ninety-nine percent of things that come before you, you’re not a rejection machine, you’re a search engine. You’re looking for the one thing that’s there. You’re a prospector.

The JRB: You mentioned a few writers just now—what is your opinion of the representation of writers of different races and genders in the literary space? Do you think literary journals have a responsibility to redress imbalances, and if so in in what ways?

Philip Gourevitch: I think that’s up to the editors. I don’t really like to say that all, or any, magazines should follow this or that purpose, but of course they must be judged by what they do and don’t do. There’s a definite diversity deficit in journalism in America, but it seems there is a much greater diversity among prominent novelists now than even in the recent past, although that is not to say that it couldn’t be much greater still. Of course, you don’t want to pigeonhole people and say, you know, ‘You’re a black gay writer, therefore you should be writing black gay fiction,’ any more than you want to say, ‘You’re a white straight writer and we’ve heard from them and therefore you don’t have anything new to say.’ So you have to be alert to all of this, but what you want is to be open to great stuff with no particular concern for where it’s coming from—but also to try to catch your own filters and notice when you seem to be missing something. And that means constantly putting out antennae.

As a parallel matter, there’s clearly an international prejudice against non-fiction. All around the world, the literature that we read in translation tends to be fiction and poetry. It’s much less likely for people to say, ‘Why there’s this fantastic book by this American about the Vietnam War, and it’s non-fiction, let’s translate it into thirteen languages immediately’, the way they would if it was a novel. The novel may not even be as good a book, but it has this supposed literary identity. But ‘literary’ just means ‘written’.

So I do think there’s a prejudice against non-fiction in the literary world. For instance Joan Didion, who is one of the great American masters of non-fiction, her novels got a little translation, but apparently she was not so much translated around the world until she wrote the memoir The Year of Magical Thinking, about her husband’s death. The masterpieces of American reportage that she did over the years were considered ‘American Interest.’ Even with my Rwanda book, I felt some of this. The book got quite nicely translated in Europe, and of course Europe has a deeper tradition of reading about Africa, because of its colonial connections, than we have in America, where chattel slavery was the connection—which wasn’t a connection, it was a disconnection. But still I encountered the attitude: ‘Why should we do a book on Rwanda when we have reporters here who’ve done good work there, in our language, and know how to speak to our people?’ It’s not an unreasonable sounding question, but you wouldn’t say, ‘Well, why should we translate this love story from Russian by Tolstoy when we have lots of people writing love stories that are much more accessible to Italians or Malawians or who-have-you?’ You would say, ‘That’s a silly argument. It’s Tolstoy.’ So that’s an interesting problem that I think afflicts non-fiction, which is often regarded the way photography used to be, as maybe not an art form. The prejudice lingers that if it’s journalism it’s not literature. There is certainly no end of journalism that isn’t literature, but there’s plenty that is.

The JRB: That’s really interesting. There’s a lot of great non-fiction coming out of South Africa that really could go far if it was in translation elsewhere. But this is perhaps a subject for another day. We have only a few more questions because we’ve already taken up quite a lot of your time.

Philip Gourevitch: That’s my fault, I talk too much.

The JRB: Not at all—we could listen all day. But to turn to the question of trends, in Africa, we take it as given that we’ve earned a rightful place on world literature’s stage, one that’s increasing in scope with every year. And you’ve mentioned that you’ve read quite widely around the continent. But what other hotspots in world literature have caught your eye, if any?

Philip Gourevitch: Over time there are these periods of ferment. There was a time when you had the Latin American novel exploding—in the nineteen-eighties, when it just seemed like everyone was discovering big Latin American novels. There was a period where that happened with South Asian literature in international publishing. And these are places with long literary traditions, but they suddenly explode: they start to be translated and to enter into the stream of world literature.

The JRB: We’ve heard good things about South Korea, for example. Have you ventured there in your reading?

Philip Gourevitch: I’ve read a couple of terrific Korean novels. I did some reporting from Korea some years ago—and there was a novelist who I read at that time, Yi Mun-yol, who was really outstanding. I went to see him, knowing from his English translations that he’d written four or five books—and he’d written something like three hundred.

Publishers often say that the market won’t support more work in translation, and to a large degree I’m sure that’s right. But publishers can also create markets that didn’t seem to exist. Think of what the Heinemann series did for African literature at one time, taking very diverse writers and essentially saying, ‘If you liked the last one you read, look for another one that has this sort of cover’; ‘look for the other ones in this imprint’. Achebe was an editorial adviser for a long time, so then other good writers wanted to be part of that imprint, and part of that group, the same way they might want to be part of a literary magazine. They want to be in this club, that club. So those moments can happen. And I think what you’re doing by starting a review in Johannesburg may be one of the many things that helps bring the work that’s happening there together in a way that helps disseminate it more widely.

The JRB: We hope the Joburg Review eventually has an impact like that. Here is a long-ish question, but it’s one that has really exercised us, and one of the reasons why we are interested in starting a literary review. And that’s, we seem to be entering an era of hardening ideologies from the left and the right, but book reviewing, on the other hand, is grounded in the idea of intellectual exploration. If book reviewing adheres to any orthodoxy it’s the tenets of liberal humanism, which are increasingly out of favour. So how do you navigate shrill demands from the left and the right for the ‘correct’ type of publication? What do you do about that problem?

Philip Gourevitch: You have to know what your agenda is, and what it isn’t. If your agenda is not to have some hard partisan outlook, you look to assign the subjects and reviews in ways that reflect that, and you will also at times probably have to publish opinions that you’re not sure are your own, but you respect the integrity of. You seek people who are prepared to engage with one another—I do think that it’s crucial at this time to try to map out some kind of sober centre of discussion, and to speak in a clear, well-articulated, thorough, non-ad-hominem voice, one driven not by a partisan predisposition but by a fair-minded consideration of what’s being done. It requires a certain kind of generosity, because you have to assume that, except for a few books that you actually deem pernicious, a lot of what you’re reviewing is a serious and important effort. And if you don’t think it’s great, it’s still worth taking seriously, it’s part of an important discussion. And then you’re going to give it to a writer who will be able to make something interesting of it, and get that across, and go somewhere beyond the book, or expand upon the book.

At the memorial service for Bob Silvers there was a good little film clip. Martin Scorsese had made a documentary about the New York Review on its fiftieth anniversary called ‘The Fifty Year Conversation’, and he brought to the memorial service a clip that had not made it into the film. It’s of Bob telling how he had received a review from an Oxford don, for whom he had immense respect, of an Isaiah Berlin book, also someone for whom he had immense respect. And the book was about the philosopher Giambattista Vico—I couldn’t follow any of the references—and these guys were friends, the don and Isaiah Berlin, and yet it was quite a harsh review. And Silvers found it awkward. And was surprised. And so he looked at it, and he thought about it, and he read up on the subject, and he went back to the don, and he said, the arguments here really seem to hinge on these underlying seventeenth-century Florentine legal opinions from these courts. And the guy’s like, ‘You’ve read these Florentine justices, I gather.’ And Bob starts to laugh, but you could see that for him it was like, ‘Yeah, he got me. He knows this better than I do.’ Anyway the conclusion that he drew was, ‘If you’re going to do this sort of thing, you have to have integrity.’ And how do you know you’ve got integrity, and how do your readers know you have integrity? Well, sometimes you’re going to have to publish something because you asked for it and you respect it, and it’s rough on one of your friends, but you’re going publish it and weather that. I think if one applies that more broadly to partisan mentalities, and proceeds without fear or favour to look for what you think is making the best contribution, that itself is making an enormous contribution.

The JRB: What do you see for the future of the literary review, on the content side, on the technical side? You mentioned that you revamped The Paris Review’s website—ten years hence, what is a literary review going to look like, do you think? What’s going to be in it?

Philip Gourevitch: Good question. Because the fact is that literary reviews in the pre-digital age existed only on paper, and that—plus the fact that most of them were fortnightly, or monthly, or quarterly—there was a kind of leisure and depth, both to the way that they were produced and written and edited and thought through, but also to the speed at which one consumed them. You didn’t just get them and they vanished; you might read an article from a few issues ago six months later. So I think what you’ve seen is that a lot of publications have now split their identity, as it were, between the print, which continues at its ongoing pace, and its ongoing depth and standard, and a briefer daily, weekly, sometimes hourly digital presence. The Paris Review took that step after I left, and you see it at The New Yorker, which has a very active website, where the dispatches are often responding to something that happened hours ago, while the magazine may have a deep plunge into something that’s been happening for years. So I think that publications have to find ways to bridge these forms and make them complementary. In some ways it’s a great opening. It’s hard to make money publishing online, but it’s also hard to lose money the way you can with a print magazine. And literary journals have never been an obvious enterprise. You know, they’re a bad bet financially.

The JRB: Oh dear.

Philip Gourevitch: Sorry, but it’s not an obvious way to make money. If you’re smart enough to start a literary journal, you’re usually smart enough to know that, and you’ve decided that you’re going do it anyway. Of course, you want to make it work as a business, but you’re also doing it for other reasons, and the internet lowers the cost of entry. You don’t have to deal with mailing and with printing and so forth. But there are things that have started virtually as one person’s blog and have expanded into full-tilt literary magazines, with many departments and staff and a business model, becoming, essentially, what a successful print magazine would have been, before. Some go to paper, some never will. But the demand is always going to be there.

I think the other thing that digital magazines can do is extend access to literary life to a much more far-flung readership. One of the first things that I do when I hit a new country, or a new city, and I’m walking around, is try to drop into a bookstore or two. You get a sense of what that side of life is about there. And I’ve certainly seen a lot of places in my African travels where there aren’t a lot of bookstores, or there’s one good one in a city, and the prices are often prohibitive. So the digital literary review in our time is also like an extension of the bookstore to everybody—not just because you can buy ebooks, but because people can read it at once on their phones or laptops. If you think about a magazine like Transition—which was one of the great literary magazines when it was published out of Makerere University in a time of rich cultural ferment—if you weren’t in libraries or major capitals, it was a very obscure thing to come across. And yet for people who were invested in that life it was an essential thing. So now you have this immense reach. And I think that’s going to be a big part of sparking African literary life in the time to come, this sense of access that did not—economically or pragmatically—exist before. And that’s exciting.

The JRB: It’s almost as if literature is tied to Moore’s Law, about the the power of the processor doubling every set number of years—as though literature’s fate is tied to that in some way.

Philip Gourevitch: Certainly literature’s production and consumption is a question of technology. The book is a pretty great piece of technology. It’s hard to improve upon. I saw a piece in The Guardian the other day that said that, at least in England, because of eye strain, a lot of people are moving back from ereaders—these are big readers, you know, people you don’t have to try to convince to read, moving back from what they thought was a convenience, back to paper. Paper is very hard to improve upon. But if paper is not an option where you are, and if the economic models don’t exist—because they don’t in much of Africa—for really being able to have an advertising base, and a subscription base, and a distribution system, for print, you have to look at the technology. It’s just an immense opening.

The JRB: A final question, to end on a lighter note. We read a lot of the The Paris Review and a lot about The Paris Review, and one fact that has always niggled is—well, who knows if it’s fact or not, but legend has it that Vladimir Nabokov cut short his interview about writing with The Paris Review of because Jeopardy! came on TV. Do you know if that’s true or not?

Philip Gourevitch: I don’t know. I wasn’t around at that time and I never heard that particular wild bit of lore. I mean, it’s conceivable.

The JRB: It’s on The Paris Review entry on Wikipedia.

Philip Gourevitch: It’s a good one—so good you almost don’t want to check it in case it’s not true.

The JRB: It gives us hope because—screens stole even his attention at one point, so there’s hope for all of us.

Philip Gourevitch: I’ll tell you something—on a lighter note—that struck me when I was reading about the archives of Paris Review Interviews to put together a four volume selection. I found that the best interviews, which were not necessarily always the writers who mattered most to me, were almost always deeply funny. There was so much wit in them. Sometimes it was because the writers themselves were funny in their answers, but often it had to do with something about the shape of it, and the rhythm of it, and the wit of its composition, or the scenario in which the interview takes place. Borges plays a very long protracted joke. He’s all charm. But even Hemingway, who’s not a laugh riot, was quite funny just by his abrasiveness—a kind of crusty impatience. And I think sometimes when we’re being serious about literature and writing, and the concerns of the world, we forget that that is not a separate enterprise from humour. And what makes you value a publication often is that while it might make you think and also might make your blood boil, it also give you a kind of joy and delight.

The JRB: Maybe one day we’ll find out if Nabokov really did watch Jeopardy! so enthusiastically.

Philip Gourevitch: There are biographers who must know. Now I want to know.

The JRB: This has been a really wonderful conversation, thank you. It’s great to have you on the Editorial Advisory Panel. Do wish us luck, we’re going to give it our best shot.

Philip Gourevitch: I do wish you good luck: good luck to the Review! And thanks for the conversation.

Index

Authors

Sony Labou Tansi

Chinua Achebe

Wole Soyinka

Liao Yiwu

Yi Munyo

Isaiah Berlin

Books

We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda by Philip Gourevitch

The Good Doctor by Damon Galgut

In a Strange Room by Damon Galgut

Sozaboy by Ken Saro-Wiwa

The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola

My Traitor’s Heart by Rian Malan

Petit Pays by Gael Faye

Gomorrah by Roberto Saviano

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

The Paris Review Interviews, Vols. 1-4

Magazines

The Paris Review

The Partisan Review

The Dial

The New York Review of Books

Transition

_____

Photos: Victor Dlamini

The 1967 interviewer was Herbert Gold, who flew to Switzerland to meet Nabokov. I quote from the introduction: “When he arrived at the Montreux Palace, he found an envelope waiting for him—the questions had been shaken up and transformed into an interview. A few questions and answers were added later, before the interview’s appearance in the 1967 Summer/Fall issue of The Paris Review. In accordance with Nabokov’s wishes, all answers are given as he wrote them down.”

This was standard practice for Vladimir Vladimirovich. I simply cannot imagine a TV set in Montreux showing a transatlantic quiz show in 1967. Perhaps it was Herbert Gold who delayed adding final touches to the interview because he wanted to watch Jeopardy!